1

Translation as a process

The process of translation may start even earlier than the reading of the text, in the building of general knowledge, language skills and lateral thinking. The first stage of any theoretical or pedagogical discussion is to look at what we read and what prior knowledge we bring to reading. The notion of schema, first coined and developed by Bartlett (1932), is based on memory, ‘literally reduplicative and reproductive’, which ‘every time we make it has its own characteristics’ (Bartlett 1932:204). All the formal and informal learning we have done, factual, abstract and emotional, every memory, good or bad, vague or detailed, including the physical sensations that go with human activity, combine to bring understanding to our reading.

As we observed in the introduction, translation at some levels may become automatised, particularly in the older, experienced translator, and especially in the case of specialisation in a restricted field. While expert knowledge helps us to produce the right answer quickly and smoothly, there may still be a great deal of working out, associating, manipulating and checking to be done. Most texts will require the reading of new material, necessitating a degree of word- and sentence-level decoding.

The notion of schema has been used in theoretical and experimental work on reading processes, enabling researchers like Rumelhardt (1977) to build models of ways in which effective reading is done. Since reading is a major part of translating, we may apply the schema model to translation.

Reading begins, and only begins, with the decoding of the words on the page. It is a complex information processing activity, and is not necessarily linear in nature. We work backwards and forwards in the text working out the meaning, confirming and correcting our apperception. While the ‘lower stage’ (print on the page) triggers meaning, the information supplied top-down from the reader’s general knowledge and memory will influence the way we construe the words on the page. We use syntactic, semantic, lexical and orthographic clues to spark the messages and narratives the author is transmitting (Samuels and Kamil 1988:27–29). Reading a text is an interactive, constantly evolving creation and manipulation of meaning. If this is what happens in monolingual reading, the effect is likely to be similar, but perhaps more complex, for the reader-translator, whose schema will be bi-cultural and bilingual.

The syntactic, semantic, lexical and orthographic clues, together with layout and structure of the text provide a ‘formal schema’. This is the physical print framework in which the reader creates a ‘content schema’. The content schema is an understanding of the informational and implicational content of the text. The translator applies the content schema to re-create the text within the framework of a new formal schema in the target language.

Formal schema: decoding the marks on the page

Jin points out that ‘the spirit and form of a text are inextricably united’ and ‘the translator needs to grasp the message by absorbing the whole body of the source text, including all the features of its language, down to its minutest particles…’ (Jin 2003:53). This is the formal schema, and the ‘minutest particles’ give us crucial information about the text.

Every text, however incoherently written, or illogically constructed, has some kind of form. The shape, size, texture and components of the text give the first clues to its meaning and message. The title will tell us what the text is ‘about’. That is perhaps an optimistic statement. In the case of literature, and even newspaper and magazine articles, authors may sometimes use a very subtle or humorous title or heading. The reader may only become aware of the meaning of the title by reading the whole work. Frequently an elegant, succinct title is followed by a colon and a phrase or two that tells you a little bit more. The colon has a meaning: it means ‘what I am actually going to write about is…’ Even in situations where the title is not entirely transparent, it is a contribution to the meaning, a clue to the writer’s attitude or character, and helps to build understanding of the work.

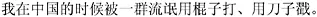

Perhaps the ‘minutest’ part of a text is the punctuation. Every language uses punctuation differently, to signal different things, and this is part of the formal schema. The following is a sentence from a test transcript, followed by two actual renderings:

In the Chinese sentence there is no overt direct object of the hitting and stabbing: it is a typical example of a Chinese zero pronoun. The comma between the hitting and the stabbing is of the type which is used in lists, so the reader can fairly safely assume that hitting and stabbing constitute a list of things the hooligans did, as in Example 1a. However, if the comma is ignored, or misread as the kind of comma that links phrases or clauses, the reader might call on schema to interpret the second zero object as the gang, as in Example 1b. So the two readings of the same sentence result in a victim schema on the one hand, and a retaliatory schema on the other. This example shows how it is inevitable (and important) that bottom-up reading of the ‘minutest’ parts of the text interacts with the common sense and logic of top-down schema.

Colons, semi-colons, dashes and commas all link parts of sentences in a meaningful way. A comma in Chinese may indicate ‘new idea coming next’, and we might want to use, instead, a full stop in an English translation (a more detailed account of Chinese and English punctuation is given in Chapter 2). Much has been written about Chinese paratactical sentences and English hypotactical sentences, variously evoked as ‘towering trees’, ‘bamboo sticks’ and ‘bunches of grapes’ (Tan 1995:482), ‘building blocks’ and ‘chains’ (Liu 1990). The translator can learn a great deal from a linguist’s analysis. It is not simply the case that long English sentences need to be broken up into short Chinese sentences or vice versa. Punctuation, including the different kinds of comma, needs to be mined for its meaning, so that the text and its component sentences can be appropriately restructured. It should be emphasised that not every sentence needs to be restructured. Thoughts which have followed the same pathways and networks in the Chinese-speaking and English-speaking brain may need to follow the same syntactic pathway on the page.

Perhaps it is patronising to point out to highly literate translators that paragraphs are also part of the structure of a text. We need to think about the respective role that paragraphs play in Chinese and English text and the differing roles that paragraphs play in various genres. Internet writing often uses many very short paragraphs, so do we, as translators, stay with the brevity, or concoct a new lengthiness? Do we shift a paragraph, or a sentence that sits well in Chinese, but sounds out of place in English? What is the writer’s intention in division of the text into paragraphs? What do those line-spaces signal? And what about the texts that have no paragraphs as such, but consist of lists, and boxes and thought bubbles? Are Chinese boxes and bubbles the same as English boxes and bubbles?

Spacing in a printed text can signal more than just the beginning and end of paragraphs or sentences. Advertising, poetry and title pages are just a few of the types of text which use both line and word spaces for visual effect. It may be that the translator can simply transpose the pattern of spaces. On the other hand, it may be necessary to modify the space patterns to make sense in the target language. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.

The formal schema of a text also tells us about time and space, events, processes, activities and physical and mental conditions. To convey these messages, the authors use all the linguistic building blocks at their disposal: nouns, pronouns, time adverbs and tense, weights and measures, verbs, adverbs and adjectives. In addition, the way these blocks are arranged and combined in patterns of coherence is a crucial part of text structure. Chinese reference chains, consisting of nouns and pronouns, for example, do not always work in quite the same way as English reference chains. A Chinese writer may foreground or highlight a protagonist or subject by not mentioning him/her/it, whereas he may background, or demote a person or object by the use of full noun phrases (Pellatt 2002:173).

Finally, there is the fact of the words on the page. For example, there is the problem of what to do with the word, or thing, or idea that seems to belong exclusively to the source language, and for which it is at least difficult, if not impossible, to find an effective, neat word or phrase in the target language. Often it is easy to understand and find an appropriate way of conveying these in the target language, for not only are the notions of time, space etc., common to all human beings, but so are physical and mental sensations and behaviour. However, while we may experience the same sensations and experiences through our similar human physicality, we may express them rather differently. Our common human knowledge helps us to express our individual and culture-specific concepts.

This is where the formal schema of the text is important. In the case of individual words and expressions it is necessary to plumb the context for meaning: the formal schema gives you a whole raft of information, ideas and sensations which will help to lead you to a good solution.

The notion of the formal schema can be extended to the question of style and register, and even to what Jin calls ‘overtone’ (Jin 2003:118) and which might also be described as ‘between the lines’ or ‘implicit’ or ‘underlying’. If we take, for example, one of the simplest, shortest texts, a certificate of birth, or marriage, or of graduation, we are faced with a text that has status and impact in law. There are not many words, and there is not much ‘reading between the lines’ to be done, but the formal schema of the source text, its layout and presentation, requires a suitably formal and solemn translation. For some inexperienced translators that may conjure the idea of long words and complex sentences, whereas what is really required is concision and precision.

There are, needless to say, conventions, and an important part of the translator’s education is to develop knowledge of conventions. Some scholars, for example, Kaplan (1966) and Connor (1984), have claimed that texts in different languages are structured differently. They may progress from general to specific or conversely from specific to general. They may be roundabout as opposed to direct, and so on. If this is the case, then the translator must be alert to this. It is indeed the case that sometimes a sentence or a paragraph in a Chinese text needs to be re-sited in the English target text, though whether this is a characteristic of Chinese writing or of an individual writer may be a moot point. We take a closer look at text structure and paragraphing in Chapter 2.

Content schema: knowledge and experience

While the formal schema goes a long way towards informing the translator, the personal, content schema triggered by the reading of the text is, of course, paramount. Our own personal experience can seriously skew the interpretation we put on information that comes our way, even when it is not commissioned as translation work.

The picture which each of us builds up, as we apply our background knowledge to the text, is the content schema. It is triggered by the decoding of the formal schema. We cannot read a text without applying our own personal knowledge and the broader and better our understanding of the world, the more successful our reading, and therefore our translation will be.

Inevitably, not every translator has the same solution and inevitably mistakes may happen. ‘While schemata enable a reader to comprehend the author’s purpose, they may also cause a reader to interpret the text in a way entirely different from that intended by the author’ (Pellatt 2002:29). There may be circumstances in which a translator, for political or diplomatic reasons may wish, or is obliged, to put a different interpretation on a text from that intended by the author (Baker 2006:37–8). The speed at which translation is done may also affect accuracy, and in the professional world translation has to be done rapidly. The very existence of translation memory software has forced translators to work faster. It is therefore all the more important that source texts are understood correctly, in terms of linguistic accuracy and within the terms of the client, before translation has even begun.

There may be a continuum of variation. At one end, in scientific and technical texts, the translator cannot deviate from the information that is conveyed. At the other end of the spectrum, a literary text may offer the translator great scope for creative writing.

Implication and inference

Texts differ in the amount and type of information provided. Technical texts may provide maximal information and require minimal inference. Literary texts often deliberately hold the reader in a state of suspense and necessitate a degree of guesswork.

As we read each proposition in a text, we apply inference. There are two broad types of inference: bridging and elaborative. Bridging inferences are logical and crucial. For example, let us take the two propositions ‘Mary loves all plants. Chrysanthemums are plants.’ We can infer that Mary loves chrysanthemums. Elaborative inference, on the other hand, is, in effect, a leap of the imagination. We all find elaborative inference irresistible from time to time, and it may be unconscious on the part of the reader. The two following propositions do not have a logical link: ‘She was crying. Her boyfriend had left her.’ We cannot logically infer that she loved her boyfriend, or even that she was crying because he had left her: we need more evidence. However, most readers would use bridging inference: they would probably assume that she did love her boyfriend and that her tears were due to having been abandoned. They would not necessarily assume that he had stolen her computer or set fire to her house.

Both types of inference are required to build the schemata that lead to successful reading and translating. Languages differ in the information, or...