- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Indian Folk Theatres

About this book

Indian Folk Theatres is theatre anthropology as a lived experience, containing detailed accounts of recent folk theatre shows as well as historical and cultural context. It looks at folk theatre forms from three corners of the Indian subcontinent:

- Tamasha, song and dance entertainments from Maharastra

- Chhau, the lyrical dance theatre of Bihar

- Theru Koothu, satirical, ritualised epics from Tamil Nadu.

The contrasting styles and contents are depicted with a strongly practical bias, harnessing expertise from practitioners, anthropologists and theatre scholars in India. Indian Folk Theatres makes these exceptionally versatile and up-beat theatre forms accessible to students and practitioners everywhere.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Seraikella Chhau

Competing spaces

From the heart of all matter

Comes the anguished cry –

‘Wake, wake, great Shiva,

Our body grows weary

Of its law-fixed path,

Give us new form.

Sing our destruction,

That we gain new life.’Rabindranath Tagore1

In June 1938, during the week that Jewish refugee Sigmund Freud arrived in Hampstead and Wilhelm Furtwängler conducted The Ring Cycle at Covent Garden, a small group of ‘Hindu dancers’ performed at the Vaudeville Theatre, London. The Maharaja of Seraikella’s sons had been brought there by ship by the Kolkata entrepreneur, Haren Ghosh. Their six-month tour would continue on to Rome and Belgrade. Suddhendra told me they filled their West End venue every night, and certainly the British press responded enthusiastically to ‘their extraordinary beauty, at once remote and passionate’ (The Times, 8 June 1938) and the ‘sumptuousness of their costumes’ (The Stage, 9 June 1938). Many reviewers found the masks very beautiful, and published photographs to prove it. The Daily Telegraph of 8 June 1938 stated: ‘There is an especial fascination to some of us in the mask convention, so impersonal yet so satisfying.’

‘Extraordinary’. . . ‘sumptuousness’. . . ‘fascination’. These reviewers inhabited a blissfully ignorant world before World War II, before Indian Independence. They could relate to the Maharaja of Seraikella’s dancer sons who spoke Her Majesty’s English and displayed such elegance and refinement. You didn’t even have to be an Orientalist to enjoy the event, as there were clearly similarities with more familiar dance styles. Indeed a Spectator article immediately saw a relationship with the home brand – having discussed the artistic merits of Western Classical ballet at length, identifying Nijinsky’s ‘Après-Midi d’un Faune’ as the ultimate in ‘pictorial movement’, Dyneley Hussey went on to celebrate the same qualities in the Seraikella show: ‘Their dancing, besides having the attraction of the exotic, has the essential quality of artistic ballet’ (Spectator, 17 June 1938). If some were bewildered, they expressed themselves with tantalised humility: ‘The body and the limbs tell a story that every native at the feast of Shiva . . . seizes, but no Westerner can guess’ (The Observer, 12 June 1938).

Now, some seven decades later, and as far in time from Edward Said’s Orientalism as that book was from the ‘Hindu dancers’, ignorance is not an option. It is simple enough for a Westerner to get on a plane and witness these dances in their native place. And once such first-hand experience is attained, they have access to all sorts of literature and other expert communications to fill out their understanding of what they have seen. In many ways, Seraikella Chhau has become the most accessible form of Indian folk theatre available to foreign scholars.

As I approach Seraikella southwards from Ranchi airport, I am struck by the lushness of the landscape. I see rolling plateaus broken by flat-topped hills, rivers and lakes. This is a forested region, scarred by the mining of coal and iron in its vibrantly red earth. The complementary green of palms and paddy-fields shines out against the colour of the soil, asserting the great fecundity of this land. I am visiting Seraikella (now part of south-east Bihar)2 at the beginning of April 2003 to join in the celebration of Chaitra Parva. Chaitra is the first month of the Hindu calendar and the community rejoices (Parva) because it is the New Year. Spring is turning to summer, the crops are at their height and the great fertility of nature is to be celebrated. Chaitra Parva takes place at a time when the productivity of agriculture is at its height, in the waiting period before the harvest. All the neighbouring regions mark this important period with one long party, and dancing forms part of their festivities.3 For Hindus, the ritual aspect of Chaitra Parva is a ‘feast of Shiva’ – it is said to celebrate the god Shiva in a form combined with his consort, Shakti, named Ardhanariswara. Shiva has lain dormant; Shakti, the Earth Mother, rouses him from his Yoga-nidra (slumber) and makes him Shiva of the Nataraja, the divine dancer of the cosmos. Shiva Nataraja sets in motion the cyclical dance of the universe. The combining of Shiva and Shakti – supreme male and female forces – symbolises the zenith of creation, the climax of fertility.

The royal legacy

The car hurtles along, slowing down suddenly and pulling onto the sandy roadside when two or three big vehicles bear down on us. The road is newly tarmacked, straight and smooth, with the odd rough patch where a bridge is yet to be built; we are cutting through a region that was once inaccessible, encircled as it is by the Saranda and Bangriposi hills. Uncolonised by Moguls from the north or Marathas from the south, the now-extinct local area called Singhbhum (meaning ‘the land of the Singhs’, or ‘Lions’) managed to retain a unique and independent identity, ruled over by the one Simha Dynasty for fifty-six generations.4 In the 1700s, when Singhbhum dissolved under pressure from tribal factions, only the smaller portion, Seraikella, remained, protected by the British East India Company (see T.N.N. Singh Deo 1954). In 1820 the Maharajas, or kings, of Seraikella signed a security treaty with the British colonial rulers and were given complete autonomy. It was during this period of undisputed safety that they began to show a keen interest in the ancient martial art and dance forms of the region.

The main royal innovator, to whom most of Seraikella Chhau’s current characteristics are attributed, was Bijoy Pratap Singh Deo, the great-great grandfather of the present king. Bijoy was educated in Kolkata between the wars where he is said to have met many great thinkers and artists including Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore. He visited Tagore’s Shantiniketan Centre for the Arts outside Kolkata – a cosmopolitan place bringing influences from all over the sub-continent and abroad. The dances devised at Shantiniketan were essentially dance-dramas, often with a poem as the starting point. Tagore and his collaborators saw no problem in combining Manipuri dance style with Keralan Kathakali, Hungarian and Russian folk dances with versions of English ballet he had seen on his visit to Dartington in Devon. Some shows were reworkings of mythological subjects, often with a focus on the woman at the centre of the narrative; others celebrated the cycle of the seasons or the powerful romance of nature.5

Those were the days when the British colonial presence brought huge opera and ballet companies to the big Kolkata venues. Bijoy was deeply affected by what he saw in Bengal and returned to Seraikella determined to infuse the dance of his region with a similar cultural poise. He wrote pieces for the Chhau repertoire, choreographing themes from Hindu mythology, aspects of nature and abstracted human experiences – among them Chandrabhaga (Moon Maiden), Mayura (Peacock) and Banaviddha (Injured Deer). His older brother, the Maharaja Aditya Pratap Singh Deo, worked on refining the masks, and went to great lengths to collect the most beautiful gems and fabrics with which the performers were adorned. Three of Aditya’s sons continued the tradition of directing, designing and performing the Chhau dances: Suvendra, a much-lauded practitioner who drowned at the age of twenty-four; Brojendra, his younger brother, who also died young, and the youngest, Suddhendra, who took over the great performing responsibilities when his brothers died. With Rajkumar Suddhendra’s death in 2001, the family’s involvement as Chhau practitioners ceased.

Competition

From the 1930s onwards, the royal family introduced their innovations in the dance form into the Chaitra Parva festival, during which a four-day Chhau competition was staged with the Maharaja acting as chief judge (J. B. Singh Deo 1973). According to Tikayet Nrupendra Narayan Singh Deo, writing in the 1950s, Seraikella was divided into two separate areas, each training and presenting dancers at the competition in the palace courtyard. Dancers from the area north of the palace, Bazar Sahi, were patronised by the royal family and those from the south, Brahmin Sahi, by leading Brahmin families. They were amateurs, agricultural labourers whose spare time and enthusiasm were harnessed by the royals and their Brahmin friends. There was clearly a strong tradition of practising martial arts and dance in the Seraikella community, and skills passed down from generation to generation. Bijoy Singh Deo quickly succeeded in introducing his new vision to the local people. For the festival competition, each Sahi was subdivided into four groups called Akharas (T.N.N. Singh Deo 1954, p. 96)6 and dancers would enter and exit from two separate corners of the dance floor, depending on their Sahi allegiance. The winning group was presented with trophies of a flag with golden tassels and a silver staff. But times were changing for the Maharajas. When in 1969 Indira Gandhi withdrew all their constitutionally guaranteed privileges, they no longer possessed funds enough to sponsor the competition.

Despite this, the impecunious royal family has managed to keep something of their tradition as patrons going, and the village families kept passing on the repertoire to the next generation. Each year, the Singh Deos get together just enough money for a cut-down version of the festival, for one night only. And in recent years the Government in Seraikella has started to revive the big annual competition – the local Departments of Tourism, Youth, Sports and Culture, Public Relations and others banding together to sponsor a Chhau Mahotsav (meaning ‘The Great Festival of Chhau’). This year’s 2003 festival is the biggest ever, employing judges from all over India, and I have been invited along as guest of honour to the District Government Administration. I am told that almost fifty ‘rural teams’, chosen by important people within their village (village Heads, panchayat elders and so on) have already taken part in an ‘Inter Village Chhau Dance Competition’– ‘a humble effort towards preservation and promotion of this unique dance form’, reads the official programme. These amateur dancers perform not only the Chhau dances of Seraikella, but also those of other regions nearby.7 Five teams have now been picked to perform on each of the three nights of the Chhau Mahotsav festival, with winners declared at the final show. ‘Attractive cash prizes are being given’ states the programme, in total amounting to a huge Rs.150,000 (though how this is divided up is not explained8). The financial incentive is important, as this is one of the poorest regions in the Indian sub-continent and the festival organisers admit that ‘acute financial shortage’ threatens all the performers’ livelihoods.

At the official festival site, carpenters are erecting huge wooden cutouts of drummers and dancers on the 1.5-metre-high stage. Behind the stage is the whitewashed building of the Government Chhau Dance Centre. According to the official 2003 programme, the Bihar government established this school in 1961 ‘to preserve and promote the cultural heritage of Seraikella’. They hold workshops and part-time training programmes here (local students pay minimal fees), and members have participated in festivals in France, Japan and the former USSR, as well as events in India. The Dance Centre’s 2003 advertisement claims that ‘about 1,500 students have successfully been trained by the Centre so far’. They are proud of the diversity of their students’ backgrounds, stating that ‘tribal students of Seraikella have joined the Centre in scores to receive intensive training’.

Women first studied here officially in 1995, when it became clear that the traditionally male-only dance should expand to accommodate enthusiasts from abroad who were knocking on their doors. In fact, foreigners like me had been coming to study with private gurus since the 1970s. Of the numerous private centres in Seraikella established to accommodate this trend, the best known is the Sri Kedar Centre, established in 1988 by Guru Kedarnath Sahoo, ex-director of the Dance Centre. He is in his late seventies and said to be ailing, but his school still attracts students from all over the world. In contrast, the royal family’s school, Sri Kala Pitha, once affiliated to the National Sangeet Natak Academy, had its assets frozen by the Bihar government back in the 1950s.9 The state grant was withdrawn and diverted to educate locals in other performance skills such as tribal dance and music. A grubby sign outside the palace advertises ‘Classes 10–12 and 6–8’, but from my personal experience I am sure no real classes have taken place in decades.

Masks

In a large, echoey room in the Government Chhau Dance Centre, a mask workshop is going on. The famous mask-makers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were all men from one family called Mahapatra who had originally been tutored in their art by the high priest of the royal temple (J.B. Singh Deo 1973).

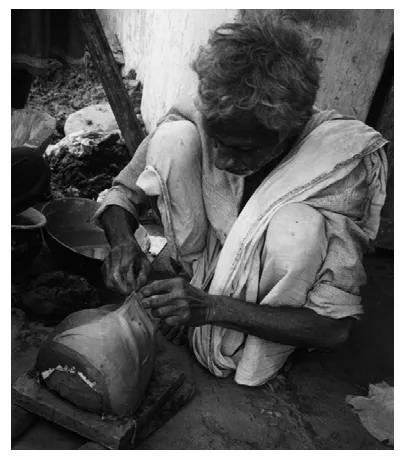

Figure 1.1 Prasanna Mahapatra making a mask.

I met Prasanna, the last of the direct line of Mahapatras, during the 1990s and commissioned a set of beautifully moulded masks from him. But he died a few years ago and his tight heritage has now been forced to expand. His nephew, Susant, is now teaching the mask-making techniques, and girls and boys from all sorts of families are learning the skill in the hope of earning a living from it. Under the supervision of the school mask-maker, the students sit on the floor moulding models out of clay from the local river. They draw finely stylised features in perfectly flowing curves with a sharp steel instrument called a karni. In an hour or two,10 the clay model will be dusted with ash before being layered with old cotton sari fabric and papier mâché, then bonded and given a smooth surface with clay slip. Once dry, the completed mask is removed from the mould, then polished and painted in a uniform shade, according to the conventional symbolic hue of the character it depicts. The mask-maker is able to vary the design according to the tastes of the dancer, but generally he uses standard colour coding – blue for Krishna, red for Ganesh, darkest blue-grey for Ratri. On top of the monochrome base, elegant black brush strokes are painted around the eyes and mouth. There is a dispute as to how the particular stylisations of flat colour and flowing black lines came about. Some regard their evolution as originating in Aditya Pratap Singh Deo’s artistry and the international influences he and his brother enjoyed at Tagore’s Shantiniketan Centre. Other scholars associate the design with Indonesian masks11 and point out that trade and cultural links between the East Coast of India and Indonesia have existed for thousands of years, possibly as far back as 3 BC.12 These are celebrated every year in the Orissan festival of Bali-Jatra.13

The masks are stylised, dreamy human faces, the designs for specific roles instantly recognisable for an audience tutored in the Chhau conventions. If they depict animals then they are given anthropomorphic form, the most important characteristic being the obviously human emotional state. For example, in Mayura, the exaggerated length of the peacock’s nose is more nose than beak, giving it a haughty expression, intended to signal vanity combined with exuberance. Despite the rigid iconography of the design, a mask will be created for one performer only, the lightweight papier mâché fitting tightly against the face. It has holes at the eyes to look...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Seraikella Chhau

- 2 Expanding Chhau

- 3 Rediscovering folk theatre

- 4 Tamasha

- 5 Re-working Tamasha

- 6 More discoveries

- 7 Therukoothu: coalescing worlds

- 8 Modern Therukoothu

- 9 The global village

- Therukoothu appendix

- Postscript

- Glossary of terms

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Indian Folk Theatres by Julia Hollander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.