This is a test

- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this comprehensive introduction to the work of contemporary French critic Rene Girard, Richard Golsan focuses on Girard's theory of myth and its connections to his broader exploration of the origins of suffering and violence in Western culture. Golsan highlights two of Girard's primary concepts--mimetic desire and the scapegoat--and employs the concepts to illustrate the ways Girardian analysis of violence in biblical, classical, and folk myths has influenced recent work in theology, psychology, literary studies, and anthropology. The book concludes with an interview between Golsan and Girard, who offers his own analysis of the appropriation (and criticism) of his work by a politically and intellectually diverse company of scholars.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Rene Girard and Myth by Richard Golsan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

From Triangular Desire to Interdividual Psychology

From Triangular Desire to Interdividual Psychology

René Girard began his career with two books of literary criticism: Deceit, Desire, and the Novel (1961) and Dostoïevski: du double à l’unité (1963). The first book is a study of five major novelists—Cervantes, Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust, and Dostoevsky—while the second book is a monograph focusing exclusively on the novels and shorter fiction of the Russian writer. In the two works Girard offers a number of remarkable insights into the novelist’s craft, but his primary concern in both is to examine the workings of what he labels “triangular,” or “mimetic,” desire.

Triangular Desire

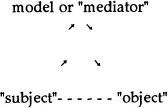

What is “triangular,” or “mimetic,” desire? In simplest terms, Girard argues that our desires are not innate or autonomous. Instead, we copy them from others.1 If I desire a particular object, I do not covet it on its own merits but because I “mimic,” or imitate, the desire of someone I have chosen as a model. That person—whether real or imaginary, legendary or historical—becomes the mediator of my desire, and the relationship in which I am involved is essentially “triangular”:

In Deceit, Desire, and the Novel Girard maintains that triangular relationships fall into two categories. The first category, described as “external mediation,” assumes a distance in space, time, social rank, or prestige between the individual who desires (the “subject”) and the model, or mediator, of that desire such that the two do not become rivals in their desire for the object Excellent literary examples of “external mediation” can be found in Cervantes’ Don Quixote, in Dante’s Divine Comedy, and occasionally in the novels of Stendhal and Proust. The second category, called “internal mediation,” involves a model or mediator who is not separated from the subject by time, space or other factors and therefore more readily becomes a rival and obstacle in the subject’s quest for the object Internal mediation is a complex and ultimately destructive process which generally typifies the nature of desire in Stendhal, Proust, and Dostoevsky. It also serves as the starting point for Girard’s critique of Freudian psychoanalysis, his theory of violence and the origins of culture, and ultimately his theory of myth.

External Mediation

Deceit, Desire, and the Novel opens with a passage from Don Quixote in which the hero announces to his companion, Sancho, his desire to imitate as well as he can the legendary knight Amadis of Gaule. Don Quixote’s intention is to become a more nearly perfect knight:

Amadis was the pole, the star, the sun for brave and amorous knights, and we others who fight under the banner of love and chivalry should imitate him. Thus, my friend Sancho, I reckon that whoever imitates him best will come closest to perfect chivalry. (Deceit, 1)

Quixote’s imitation of Amadis affects his actions, his emotions, and his judgment He decides that he, like his hero, must have a beloved to whom he can devote himself completely and through whom he can suffer the torments of love. He chooses a rather plain, ignorant local farm girl, Aldonza Lorenza. Don Quixote’s desire transforms her in his eyes into the ravishing and beguiling Dulcinea del Toboso. Although he does not even know her and rarely if ever speaks to her, he dedicates his deeds of valor to her and suffers for her as if the two of them were really deeply and passionately involved. Don Quixote even goes so far as to retire to the Sierra Morena mountains to do penance for her. Even here, he is imitating Amadis, who had been ordered by his beloved, Oriana, to perform a similar penance. Don Quixote’s imitation of Amadis is explicit As he prepares to begin his penance, he states:

Long live the memory of Amadis, then, and let him be imitated in so far as may be by Don Quixote de la Mancha, of whom it shall be said, … that if he did not accomplish great things, he died in attempting them. I may not have been scorned or rejected by Dulcinea del Toboso, but it is enough for me, as I have said, to be absent from her. And so, then, to work! Refresh my memory, O Amadis, and teach me how I am to imitate your deeds.2

Don Quixote’s triangular, or mimetic, desire proves contagious. Sancho Panza, a simple farmer concerned only with filling his stomach before becoming Quixote’s companion, imitates his master when he develops a desire to become governor of his own island and to gain for his daughter the title of duchess. According to Girard, these desires “do not come spontaneously to a man like Sancho. It is Don Quixote who has put them in his head” (Deceit, 3). Thus the knight becomes the model, or mediator, of his page’s desires, just as Quixote learns his desires from Amadis. In both cases reality has been transformed, and the judgment if not the perception of both men has been severely impaired. Leaving behind a comfortable existence as well as their responsibilities, the two set out on a harebrained search for glory. What they encounter is the banal, everyday world of the Spanish countryside, but in the fevered brain of Don Quixote, driven by dreams of imitating Amadis, this world is transfigured into a dangerous, fantastic place full of evil, mysterious knights, and damsels in distress. Even the most innocuous objects are transformed completely: a barber’s basin becomes the legendary helmet of Mambrino, sheep become enemy warriors, and, of course, windmills become fearsome giants. As Girard affirms, “Triangular desire is the desire that transfigures its object” (Deceit, 17).3

Don Quixote is not the only literary masterpiece with striking examples of external mediation, where the subject, in this case Don Quixote, imitates a model removed in space and time, the legendary Amadis of Gaule. In an article entitled “The Mimetic Desire of Paolo and Francesca” Girard argues that the passion of Dante’s famous lovers in The Divine Comedy is not so spontaneous as is frequently assumed but is in fact the result of their reading the story of Lancelot together:

When they [Paolo and Francesca] reached the love scene between the knight and Queen Guinevere, Arthur’s wife, they became embarrassed and blushed. Then came the first kiss of the legendary lovers. Love advances in their souls in step with their own progress through the book. The written word exercises a veritable fascination. It impels the two young lovers to act as if determined by fate; it is a mirror in which they gaze, discovering in themselves the semblances of their brilliant models, (“double business,” 2)

Although Stendhal’s Scarlet and Black is a novel dominated by internal mediation, it, too, provides notable examples of external mediation. The novel’s young hero, Julien Sorel, is constantly trying to live up to the example set by Napoleon Bonaparte. Julien imitates his hero’s desire not only in his aspirations to achieve military glory but in his belief that it is his duty to seduce the women around him. When Julien decides that he must possess Madame de Rênal, the woman whose children he tutors, his decision has less to do with Louise de Rênal’s charms than with his conviction that Napoleon would have set out to conquer her. As Stendhal remarks, “Certain of Napoleon’s remarks about women, … gave Julien then, for the very first time, a few ideas that any other young man of his age would have thought of long before.”4 Through Napoleon’s mediation, all the stages in the seduction of Louise are transformed in Julien’s mind into so many military confrontations and triumphs. Mme. de Renal becomes “an enemy he ha[s] to fight.”5 It is his “duty” first to take her hand in the garden and later to go to her room. So intent is he in playing the part sketched out by Napoleon, of imitating Napoleon’s own bold pursuit of women, that he fails to take pleasure in the actual seduction. After making love to Louise for the first time, Julien wonders, “Is being happy, is being loved, no more than that?”6 Mimetic desire thus in no way guarantees sensual or sexual gratification in the possession of the object In fact, the opposite is the case.

In Remembrance of Things Past Marcel Proust also offers interesting examples of external mediation in a novel dominated by internal mediation. The young narrator, Marcel, is a passionate admirer of the writer Bergotte. Because Bergotte is a writer, Marcel wishes to become one as well. Bergotte admires the actress Berma, and it is therefore one of the young narrator’s most ardent desires to see her perform. Just as Marcel desires what Bergotte desires, so he remains indifferent to those things that do not interest the older man. As Girard remarks, Marcel’s stroll along the Champs Elysées leaves him cold because Bergotte has failed to describe the famous avenue in his writings.

As with Don Quixote and Julien Sorel, the desirability of the object stems not from its own merits but from its designation by the mediator. Moreover, those objects which are designated are transformed in the eyes of the desiring individual such that they assume a magical aura that they do not really possess. Finally, although the model or mediator’s influence is overwhelming, the distance between him and the desiring individual is so great in terms of space and time or status alone that he in no way interferes with the individual or becomes his rival in the quest for the object Amadis is a legend, and Don Quixote would never dream of competing with him even if it were possible. Napoleon had died on St Helena, and Julien knows of him only through books and conversations with an old army surgeon who had served in the Emperor’s Grand Army. Bergotte belongs to the world of the adults, a world which the child Marcel observes and admires but only from the outside. Sancho Panza may share Quixote’s adventures, but it would never occur to him to compete with his master. The harmony that exists between knight and page is never disrupted by rivalry. Once, however, the distance between the desiring individual and the mediator is no longer so great as to prevent such rivalries, a dangerous threshold has been crossed. External mediation gives way to internal mediation.

Internal Mediation

In its simplest manifestations internal mediation appears as easily discernable and straightforward as external mediation. In Scarlet and Black Monsieur de Rênal decides to hire Julien Sorel as his children’s tutor because he believes his local rival, Monsieur Valenod, intends to do the same. Later Valenod will attempt to hire Julien himself precisely because Julien is now in the employ of Monsieur de Rênal. For both men, Julien’s value is a function of what each rival perceives as the young tutor’s desirability in the eyes of the other. Neither man really cares much for Julien or his talents, and both are indifferent to the educational possibilities the tutor offers their children. In this example of internal mediation, the most obvious change from external mediation is the rivalry between model and mediator (Rênal and Valenod are each other’s mediators), but other changes have occurred as well. The spatial and temporal distance between subject and mediator has decreased considerably. Valenod and Rênal are neighbors living in the same town at the same time. Their difference in terms of social status is not so great as to prevent them from becoming rivals. Neither is an idealized god-like hero for the other, as Amadis is for Don Quixote and Napoleon for Julien. In fact, the two men come to resemble each other a great deal through the identity of their desires. As the rivalry itself effaces what differences remain, they are finally no more than each other’s doubles.

Another significant change from external to internal mediation is that the object of desire designated by the mediator has become much more precise. Girard remarks that in Don Quixote “Amadis does not indicate precisely any object of desire but on the other hand he designates vaguely almost everything …;” (Deceit, 84). The same can be said, to a more limited degree, of the influence of Napoleon on Julien or Bergotte on Marcel. For Rênal and Valenod, however, the object of their rivalry is quite precise, and no substitutes will do. Finally, while Don Quixote’s and Marcel’s imitation of their models is essentially a source of pleasure for both, Rênal and Valenod’s imitation of each other is a source of anguish for the two men. Because the mediator in internal mediation desires the same object and is a rival, he is also an obstacle in the path of the individual who copies his desire. The inevitable result is confrontation and struggle over the desired object Thus, internal mediation always results in what Girard describes as conflictual mimesis.

In Deceit, Desire, and ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Series Editor's Foreword

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter One: From Triangular Desire to Interdividual Psychology

- Chapter Two: Sacrificial Violence and Scapegoat

- Chapter Three: Myth

- Chapter Four: The Bible: Antidote To Violence

- Chapter Five: Girard's Critics and the Girardians

- Interview

- A Venda Myth Analyzed

- Bibliography