1 Something worth writing about?

Introduction

Teaching children to write can be exceptionally rewarding work. If you have been close at hand while young writers find a voice that is uniquely theirs and begin their early mastery of the written word, then you are fortunate indeed. Writing at its best is a powerful medium: it allows us to recount experiences, real or imagined; to express our thoughts, feelings and ideas; to argue, advocate and persuade. As they learn to do these things, children grow to think how writers think, to feel how writers feel, to experience what writers experience, and to write how writers write. And good writing can change things for the better: we need only to think of the power of a good letter of application or a well-written complaint; either can have an immediate and sometimes dramatic effect on our lives. For those lucky enough to be shown how to do it, there is true delight to be had in that sense of achievement and fulfilment which comes from knowing that one has written something and written it well. To leave children unable to write, more particularly unable to write well, can have a direct and damaging effect on the options that might be open to them in their adult lives.

Small wonder then, that the teaching of writing in our schools has been given such high priority in recent years. In England, it would not be exaggerating to say that our teaching has gone through something of a revolution. The practices of modelling for, sharing with and guiding children to help them become confident, independent writers are very much more widespread than they were a decade ago. In many schools, they are so firmly embedded that they are a natural part of our daily teaching. These are practices which attend explicitly to the skills of the writer and show children how writing is made. And we should applaud them and all the teachers who have worked so hard to sustain them in their regular teaching practice.

And yet there seem to be so many primary schools in which the teaching of writing remains a significant issue and area for development. Whether it is through national test results, inspection by the Office for Standards in Education, or a school’s own careful assessment and analysis of children’s written work, many identify improving children’s writing as a major concern. For many teachers and school leaders this can be frustrating to the point of exasperation: after all, they have worked so hard at implementing the recommended strategies, at planning, at marking and assessing. And still there seems to be something missing.

We speak to a great many teachers in the course of our work and most of them identify a very similar set of issues and problems in relation to writing in their schools. For all the hard work that has gone into addressing it in recent years, spelling persists as a challenge to many young writers. Even when they manage to spell difficult words in the lessons we have devoted to teaching it, getting correct spelling to be a natural part of independent writing is a challenge of an entirely different order. We are all very well aware of how a lack of confidence in his ability to spell can affect a young writer’s willingness to write. Then teachers often talk of children’s limited experience, often of their limited vocabulary, and often of a perceived connection between the two. A lack of imagination is also widely identified: why do they seem to have so few and such limited ideas? All these factors combine to give rise to that most familiar of cries, ‘I don’t know what to write!’ And we have all worked so hard.

This gentle parody might serve to illustrate something of the problem:

Remembering to open some sentences with a subordinate clause, the young writer dutifully began. It was a warm, sunlit afternoon and the stuffy room was filled with his classmates, all eager to show off their hard-earned skills.

‘That last sentence was impressively long,’ he thought to himself, ‘But I may have used a few too many commas.’ He knew very well that he must show his command of a range of punctuation: colons; semi-colons; even dashes—if only he could find a way to work some of those in.

‘Stop!’ he could almost hear his teacher cry. ‘Remember what we’ve been talking about: think of your reader.’ And she was right. Perhaps it was time to ask a question to draw his reader in? Should he add some shorter sentences to help build tension? This writer knew all about tension. Palms sweating, he remembered the dramatic effect of short sentences. Very short. Tiny. If the passive voice was used for the next sentence, the tension would become almost unbearable. Who had written that last one? And why?

There could be no doubt about it: this was a writer who could really see the craft.

‘Look, look!’ they cried. ‘There’s the craft!’ I could see the craft and it was bright and shiny with all lights on it and it was full of aliens and they came towards me and there was a big fight.

‘POW! POW! POW!’ I shot them with my laser gun and I killed them all until they are all dead and the end.

Perhaps it is a little unkind but, as you will have guessed right away, no real writer ever wrote it. Yet the problem it illustrates will be familiar to many teachers: there is so much more to effective and engaging writing than the slavish application of technique. What we have all learned to call ‘the craft of the writer’ is about much more than remembering all the ‘tricks of the trade’; speak to most writers and they will tell you that there are very few of those. What is more, when we become overly concerned with such techniques it can easily make our writing tiresomely self-conscious: at best laboured and labouring; at worst just plain clichéd. And when the young writer imagined in this piece suddenly finds a story raging in his head like a film or a video game, that frail veneer of technique quickly deserts him. All of which begs the question: What does make a good writer and what is good writing?

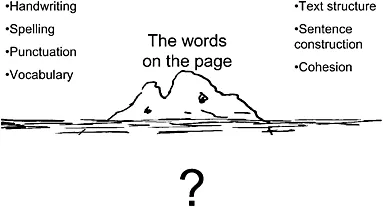

Once we have written something and given it up to the reader, the words are everything. Sometimes they may interact subtly and beautifully with illustrations, photographs, sounds or even video. Even then, what we write has to stand alone and do its own work: the writer is not generally on hand to explain, interpret or correct. Yet good writing can entertain, inspire, illuminate, clarify, and sometimes even move the reader to tears. We know that such writing has real ‘depth’ to it: a depth of experience, of feeling, and of subtle skill. In many ways the words that appear on the page are only ‘the tip of an iceberg’. The iceberg is a widely used metaphor and we are all familiar with the idea that the greater part of it lies beneath the surface, mostly out of sight. We want to use that familiar image to propose a model of how we might rethink what makes children good writers and how we can all help them to get better.

The iceberg model

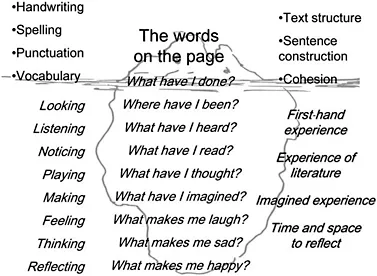

The ‘iceberg’ model we propose (see Figure 1.1) builds through four stages to offer some analysis of what might be needed to make a writer, and then suggests a number of headings under which a school can take deliberate and planned action to create that writer in every child.

When a child (or anyone for that matter) writes, the words we see on the page are all we have. Whether we read them as a teacher, a parent, another child, or even an external examiner of writing tests, we have only what we can see to celebrate, judge, applaud, criticise, or simply enjoy. And when we see those words, we can apply very particular criteria to judge them and maybe even assign them a level according to the National Curriculum. Young writers are regularly judged in this way. We should be very clear that the skills and abilities that are so judged are vital and that nothing we say is intended to detract in any way from the importance of teaching them. We have placed these skills ‘above the surface’ in our model because they are the most readily seen, often the most straightforward to judge, and often appear to be the most ‘teachable’.

Figure 1.1 The words on the page as the ‘tip of the iceberg’

We suggest that it is in the teaching of these very ‘visible’ writer’s skills—spelling and handwriting, vocabulary, punctuation and grammar, text structure and cohesion—that the dramatic changes in practice of recent years have been most evident. There has been a strong emphasis on assessing and analysing what appears on the page when children write, identifying those elements of the visible skills which need developing, and focusing our teaching very deliberately on those. We may, for instance, discover through our analysis of assessments that children seem to have a particular problem with unstressed vowels in polysyllabic words. As a result of this we can develop clear strategies to address the perceived problem and conduct further assessments at a later date to judge how much difference our teaching has made. For addressing particular technical writing skills, this approach can be highly effective.

If we pursue the metaphor of the iceberg further though, it may reveal another problem which is so often experienced by the teachers with whom we work. However big or small an iceberg might be, the proportions above and below the surface will remain constant at about one-ninth above and eight-ninths below. So if we were to try to increase the size of a real iceberg just by adding more and more ice above the surface, eight-ninths of it will sink out of sight. Keep doing this for too long and the iceberg would probably become unstable and capsize. So what might happen with the metaphorical iceberg of children’s writing? Many teachers can relate to the experience of working away at particular sets of skills, for example, spelling, finding that children complete all their exercises and worksheets accurately only to see those skills disappear when they are asked to write independently. Perhaps they have ‘sunk’ below the surface? We suggest that if you want more significant and sustainable improvement in what appears on the page, improvement that is appreciated not only by you the teacher but by the writers themselves, you may also need to look a little further and deeper at what lies beneath the surface.

The importance of experience

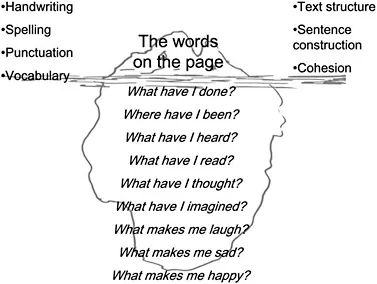

In Dear Mr Morpingo, Geoff Fox takes us ‘inside the world’ of the children’s writer Michael Morpurgo. He tells us that almost every time the writer gives a talk in school, Michael is asked the same question: ‘Where do you get your ideas from, Mr Morpurgo?’ That question is a very good one. How is it possible for one man to produce such an extraordinary range of such high-quality writing? Is it because his spelling is so exceptional, or that he has particularly beautiful and fluent handwriting? Both may be true, but what is clear is that the answer to the question ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ is as complex and difficult to fathom for Michael Morpurgo as it is for any other writer. We suggest that much of the answer lies beneath the surface and may not be so easily visible (see Figure 1.2).

When we write, we draw on experience, and we need more than just our technical skills. Our ability, enthusiasm and inspiration to write will be profoundly affected by where we’ve been, what we’ve seen, heard, touched, felt, smelled, or even tasted. What have I read? What have I thought and imagined? And how am I personally affected by all these experiences? What makes me happy or sad, moves me to laughter or tears, makes me hopeful or despondent? The answers to those questions are importantly different for all of us and yet, we suggest, can have a profound effect on the writer we might each become.

Figure 1.2 What lies beneath the surface?

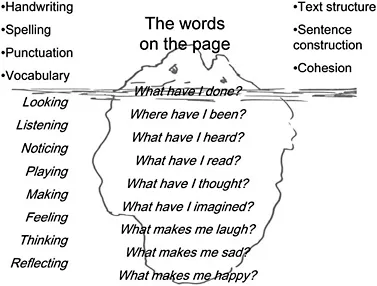

We suggest that a richness and diversity of these experiences encourages the development of another set of writer’s skills (see Figure 1.3): less visible on the page, less technical and less obviously ‘teachable’, but certainly no less important.

Writers need to look, listen, feel, smell and taste. And when they do all those things, they need to notice. So many good writers have an eye—or an ear or a nose—for detail. It is so often in the noticing of such detail, and the skilful use of it in their writing, that they are able to share experiences with us and draw us as readers into them. Good writers can not only paint a grand landscape in words, they can also draw our attention to some tiny detail that evokes a time, a place or a person with extraordinary clarity. When they hear, it is not only the everyday sounds that are all around us; it is also the particular and delightful details of the ways people really speak to each other. They notice how people look or don’t look at each other when they are talking, how the ways in which they sit or stand or move all give us clues about what they are thinking and feeling.

The widespread use of the term ‘creative writing’, most usually applied to fiction and poetry, can easily lead us to forget that all writing is, in essence, a creative process. Until we write, there is nothing on the page and whatever finishes up there has been created by the writer. Creating is fundamentally about making, about fashioning, shaping and crafting. But creating can also be a playful process and good writers may be very playful. This is not just about a willingness to be inventive with words on the page, important though that is. It is also about the vital relationship between play and imagination. In their role play, young children are capable of creating and sustaining imagined worlds and living out stories in the world they have made, be that world a home, a shop, a magic castle, or even another planet. In essence it is the same capacity as that shown by Philip Pullman in the remarkable His Dark Materials trilogy. Entire worlds are invented and given life with extraordinary consistency.

Figure 1.3 Some other writers’ skills?

The last sets of skills we identify are those of thinking, feeling and reflecting. In many ways these present the greatest challenge to our practice and to current educational orthodoxies. Thinking, feeling and reflecting need time and space, both of which are difficult to find in many primary schools. They are not always driven by objectives and their effects cannot always be seen in children’s writing the day after tomorrow. But most writers know just how important it can be to take time, to let ideas take root and grow, and to return to them more than once. There is a very understandable temptation to believe that the best way to learn to write a complete piece in under an hour is through repeated, timed practice. In order to prepare children to face that ordeal, some practice of this kind may be helpful, but it is never going to create writers. Take time to develop children fully as writers, we suggest, and they will perform well in any test anyone chooses to give them. If we teach them to take tests, they might also perform well, but they will never make writers.

When we use the iceberg model during our in-service work with teachers, it is generally recognised and accepted as a clear way of analysing a particular problem. Like all such models, of course, it is deceptively simple. Though we have tried to outline them as clearly as we can, the experience and skills that lie ‘beneath the surface’ for a writer are very complex and subtly different for every young writer we teach. And if the iceberg metaphor holds, something like eight-ninths of what makes a writer lies in this murky, sub-surface domain. Many teachers are also quick to recognise how much the experience and subtle range of skills that lie beneath the surface will vary not just from one child to another, but from one school to another. Many feel that their children are at a distinct disadvantage from the start. Some will arrive at school with a glorious richness and diversity of experiences, a growing love of literature that has been devotedly nurtured in them by their parents since they were tiny, and an imagination that surprises and delights us with its capacity to play, invent and create. Other children seem to have rather less. At that point some teachers might be forgiven for throwing up their hands in despair and lamenting the unfairness of it all, the crude brutality of league tables and the failure of those in power to realise the struggle that we face. But to their enormous credit, most teachers remain very positive and are eager to explore what they might begin to do about it all. That is what this book is fundamentally about. Those capacities teachers have developed for the deliberate and focused teaching of particular writing skills remain essential and we show how you can keep right on using them. But this is not another book about how to teach spelling or handwriting or grammar or how to recognise and write different non-fiction text types. There are plenty of those on the market and many teachers have also benefited from a good deal of in-service work to address those very particular teaching skills. Our central concern is to introduce and illustrate some teaching approaches that build on the essential writing capacities that lie beneath the surface, that are harder to see, perhaps more subtle to teach, but no less vital in the development of young writers. Equally, we address very particular and practical teaching strategies which help the young writers’ experience to ‘break the surface’ so that when they write they are able to draw on all they know, have experienced, what they think and what they feel. In taking this approach, we suggest there are four essential elements (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Four essential elements

First-hand experience

Ask a good teacher of the early years—or any good teacher for that matter—and they will tell you just how vital first-hand experience is for all learning. If a richness of experience is essential for a writer, then it has to be gained at first hand and we need to bring all our senses to the process. This may seem obvious, but it is not always easy to do if we feel that time is so precious and pressured. Some developments in recent years seem to have resulted in primary school children spending more and more time in their classrooms, sitting at their desks. And when they do get out of the classroom, we are often so determined to meet our learning objectives that we give them little time to look and listen, touch, feel and smell what is around them. This is not to suggest that the first-hand experiences we offer to children should be unstructured or woolly, rather that we might think more deeply about how we draw on them with the children. First-hand experience is something that you have, not something that is packaged and given to you.

Early years teachers can...