![]()

1

A Public Opinion Model

Public opinion, if we wish to see it as it is, should be regarded as an organic process, and not merely as a state of agreement about some question of the day. (Cooley, 1918, p. 378)

A THREE-DIMENSIONAL

INTERACTIVE SYSTEM

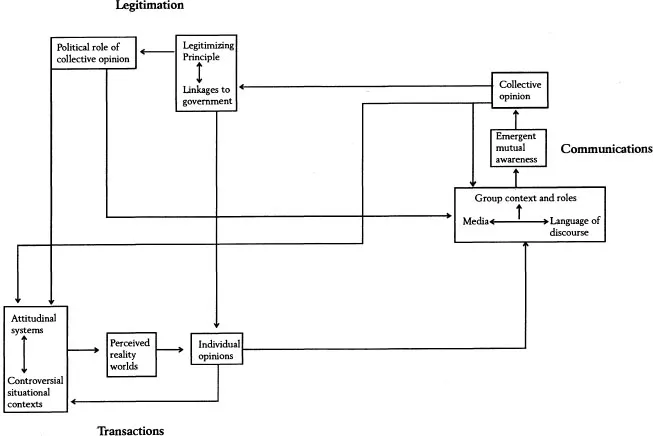

Public opinion on particular issues emerges, expresses itself, and wanes as part of a three-dimensional (3-D) process in which individual opinions are formed and changed, these individual opinions are aroused and mobilized into a collective force expressive of collective judgments, and that force is integrated into the governance of a people. Associated with each dimension is a corresponding subprocess: (a) transactions between individuals and their environments, (b) communications among individuals and the collectivities they comprise, and (c) the political legitimation of the emergent collective force.

These three processes are interactive aspects of the larger, continuous process so that their significance has to be understood in relation to each other. This conceptualization of public opinion as a multidimensional interactive process serves as an anaytical model for studying public opinion.

Three implicit characteristics of this model of public opinion as process that should be made explicit at this time are:

1. None of the three dimensions of public opinion is inherently antecedent to any other.

2. The three dimensions form an interactive system that is not characterized by a unidirectional causal flow.

3. Each dimension is itself modeled around interactions related respectively to the transactional, communicative, and legitimizing dynamics of public opinion.

Each of the three dimensions can be described in terms of how the subprocess associated with it links a particular set of variables, namely:

1. Transactions: This subprocess has to do with the interactions among attitudinal systems (consisting of beliefs, affective states, values/interests), controversial situational contexts, and perceived reality worlds that lead to the emergence of individual opinions.

2. Communications: This subprocess, which creates collective opinion as a social force by developing mutual awareness of one another’s opinions, involves the interactions between the language used in public discourse and the group contexts and roles related to that discourse.

3. Legitimation: This subprocess establishes the political role of collective opinion through the interactions between the principles that establish whether collective opinion is politically legitimate and linkages of collective opinion to government.

Figure 1.1 models this understanding of public opinion as process rather than as a condition of or decision by a society. Note that the public opinion process as depicted in Fig. 1.1 forms an interactive system and not a sequence of causally linked stages of development. By way of illustration, part of the situational contexts out of which individual opinions arise in contemporary democracies are the collective opinions which individuals experience—through nonpolitical as well as political contacts—and expectations that opinion should and, in fact, does have a legitimate role in the political life of a society. Both these elements affect the public opinion process at all stages rather than each being characteristic of a particular stage.

Intrinsic to this model of public opinion as process is the realization that public opinion is neither a group, institution, or structural aspect of a society nor the discrete states of mind of a set of individuals. Rather, it refers to continuous interactions and outcomes. Davison (1958) referred "to action or readiness for action with regard to a given issue on the part of members of a public who are reacting in the expectation that others in the public are similarly oriented toward the same issue" (p. 93). He contrasted this perspective with the view that public opinion is the majority view (e. g., as measured in a poll), the ideas that dominate public communications, or that act as an agent of social control. To demonstrate public opinion as process, instead of describing a given state of public opinion, Davison traced a sequence of stages, namely: The emergence of a public issue, the role of leadership in gaining public attention, the onset of public debate and discussion, the continued interchange of individual opinions, which leads to awareness and expectations concerning the opinions of others, which, in turn, may result in opinion change and, finally the disappearance of the issue in public thinking. Our model adds to Davison’s description the idea that at each stage of development there is a multidimensional interaction of psychological, sociological, and political elements.

FIG. 1.1. The Public Opinion Process.

The model accommodates existing middle-range theories derived from separate disciplines without reducing the many aspects of public opinion to one dimension. The individual elements of the model, as elaborated in this work, represent the tested output of empirical research. The model’s contribution is to explicitly structure the separate dimensions of the public opinion process and their component elements into a multidimensional, integrated, ongoing phenomenon. In doing so, the model resolves the old and ultimately sterile controversy as to whether public opinion is really no more than an aggregate of individual opinions or whether it is a collective phenomenon that is reflected in individual opinions. The model also helps us examine the interrelations among the psychological, sociological, and political dynamics of the public opinion process. Thus, it avoids the twin fallacies of reductionism and reification.

Before turning to the details of the model’s three dimensions, it is useful to review briefly how the model affects how we think about public opinion.

THE SIGNIFICANCE

OF MULTIDIMENSIONALITY

There is a long-standing theoretical controversy as to what attribute or quality defines the essence of public opinion, for example, whether it is the majority position or the dominant opinion (Lang & Lang, 1983). Underlying such controversy is the unidimensional assumption that there is one central quality that defines what is truly public opinion, whether that quality refers to individual opinions, some kind of collective structuring of individual opinions, or the political role of opinions. Integral to the assumption of unidimensionality is that there is a single causal flow at work so that, no matter how complex public opinion may be, it is possible to identify a common underlying causal factor, or set of factors, that explains the rise and development of public opinion.

In opposition is the multidimensional stipulation that public opinion exists simultaneously at a number of levels of reality, each characterized by distinctive causal processes. This view has its roots in the realization that public opinion does not merely exist as a summarization of opinions but is in a constant process of emergent development. An early expression of this realization is Bryce’s description of the stages through which public opinion must go before opinion begins to affect government (Bryce, 1891). These stages proceed from (a) a rudimentary form characterized by expressions of individual opinion that are in some way representative of general thought on an issue; to (b) a stage at which individual opinions crystallize into a collective force; to (c) a third stage in which after discussion and debate definite sides are taken; and then to (d) the final stage in which action has to be taken, typically as a member of some group or faction.

Our multidimensional process model goes beyond Bryce’s formulation in that it does not assume a fixed, unidirectional sequence of transitions. Instead, it recognizes that a complex set of processes are at work at each stage and that these processes are interactional rather than unidirectional. This recognition incorporates the findings of public opinion researchers who have investigated such varied phenomena as the relation of opinion to underlying beliefs and values; socioeconomic position and political leadership; the impact of events and communications on the movement of opinion; political socialization; interaction between opinion leaders and followers; the role of mass media in agenda setting; and personal versus impersonal forms of communication. Without giving up the notion that there is a life history of public opinion on any particular issue, the multidimensional process model requires us to think about all these phenomena as existing at each stage.

INDIVIDUAL VERSUS COLLECTIVE ASPECTS

OF PUBLIC OPINION

A problem inherent in the term public opinion is how to differentiate between its individual and collective aspects, and then reconcile them. One impediment to a satisfactory resolution of this problem has been a proclivity to reify the concept of public opinion, that is, to conceptualize the relationship of the public opinion process to collective action in a way that transforms the process into a being or thing that acts in its own right, separate from the individuals who make up the collectivity. The propensity to reify the public opinion process stems from the fact that although opinions are held by individuals, there is a feeling that the process has to do with something more than the thought and behavior of individuals and that "there is some social reality beyond individual attitudes" (Back, 1988, p. 278).

Social scientists have long been sensitive to the danger that asserting that public opinion involves more than individual opinions can lead to the "group mind" fallacy, with public opinion personified as "some kind of being which dwells in or above the group, and there expresses its view upon various issues as they arise" (E Allport, 1937, p. 8). It is especially important that those who maintain that public opinion involves collective phenomena with a reality distinct from individuals should also recognize that this does not mean that public opinion is a distinct being that, in any meaningful way, can be said to think, feel, decide, or act. Discussing the public opinion process as if it is an acting entity directs attention away from its actual complexity as a collective phenomenon. The reality is that there is a never-ending flux in which the balance of individual opinions and coalitions of opinions shifts back and forth, a flux in which the relevance and importance of different issues continuously change. Reifying the public opinion process muddles our understanding of this reality, even if, when pressed, we hasten to acknowledge the fallacy of reification.

Clarity requires recognizing that when we say, "Public opinion is aroused," "Public opinion has spoken," or "Public opinion has bestowed its mandate," we are using what is little more than a journalistic or literary metaphor. But even as a journalistic metaphor, reifying public opinion can have pernicious effects by leading to misinterpretations of political reality. This is readily evident in news analyses of the meaning of election results, of what mandate has been decreed. The reality is not that the electorate, as a corporate body, has reached a new consensus on issues of the day but that a different balance of political power has come into place. Those who lose an election have not, as components of the larger body, changed their opinions. They may recognize the fact that they are not in power, they may change their strategies and tactics, but in all likelihood, they mostly continue to promote the same basic policies they have in the past.

The fact that election results can have a significant impact on how a democracy is governed does not mean that political cleavages based on conflicting values and interests have somehow been, at least temporarily, resolved. They persist, though sometimes in altered forms. Also, although the losers do not disappear, over time, winning and losing particular elections can affect the ability of contending parties to persist as viable political forces. Metaphorical references to public opinion having reached a decision should not be allowed to confuse thinking on these matters.

Unfortunately, the realization that public opinion is not a superindividual actor often leads to the reverse fallacy of reductionism, that is, analyzing the collective aspects of the public opinion process only in terms of its individual components. Contributing to the reductionist perspective in the study of public opinion is the fact that over 50 years of empirical research have been dominated by survey research methodology. As Back (1988) observed, this is "a very individual oriented method, adding up individual opinion to reach a societal characteristic and corresponds to our individualistic society" (p. 278). He further observed that this extreme individualism has hindered the development of a general definition of public opinion that is not restricted to contemporary American and European society.

Illustrative of the reductionist approach to the study of public opinion is this definition:

Public opinion refers to people’s attitudes on an issue when they are members of the same social group. ... The key psychological word in this definition is that of "attitude" ... (namely), the socially significant, internal response that people habitually make to stimuli (Doob, 1948, p. 35).

Although this definition acknowledges group membership as an aspect of public opinion, there is no question that the essence of public opinion as Doob sees it lies in the expression of individual attitudes.

F. Allport (1937) left open "the possibility that a superior product of group interaction may exist," but nonetheless asserted that "if there is such an emergent product, we do not know where it is, how it can be discovered, identified or tested, or what the standards are by which its value may be judged." (p.11) In accord with this point of view, Allport listed 13 items as constituting the phenomena to be studied under the term public opinion. Of the 13 items, 7 explicitly refer to the individual, although in some cases a collective context is acknowledged:

They are behaviors of human individuals.

They are performed by ... many individuals.

The object or situation they are concerned with is important to many.

They are frequently performed with an awareness that others are reacting to the same situation in a similar manner.

The attitudes or opinion they involve are expressed or. ... ... ... individuals are in readiness to express them.

The individuals performing these behaviors, or set to perform them, may or may not be in one another’s presence.

Being efforts toward common objectives, they frequently have the character of conflict between individuals aligned upon opposing sides. (F. Allport, 1937. p. 13, italics added).

Although Allport’s other six points did not stress so explicitly that public opinion refers to the thoughts and behavior of individuals, they related to individual phenomena such as verbalization and action or readiness to action.

Even when individual thoughts and actions are examined as manifesting themselves in aggregations, the reductionist understanding of public opinion will exclude the possibility that collective qualities may emerge that involve more than the thoughts, feelings, and behavior individual (E Allport, 1937). The following is one illustration of this perspective:

I do not want to imply that the public is any more than the sum of all its parts. Clearly, as in any assemblage of people such as a town meeting, some will feel the issue is irrelevant, and having no opinions they may not participate. Public opinion in such cases is the opinion of those who have preferences and choose to participate. The saliency of the issue to a given individual and his resulting intense participation might well cause his opinion to weigh more heavily in some linkage processes. (Luttbeg, 1974, p. 1)

In contrast, others who insist that only individuals think and behave, and not collectivities, may still recognize the reality of a collective dimension to the public opinion process. Lasswell (1927) explicitly rejected the idea that "collective attitudes" relate to a superorganic entity that exists "on a plane apart from individual action," (p. 27) but...