![]()

1

Composition and Diversity

RICHARD L. MORELAND

An important aspect of every group is its composition—the number and types of people who belong. Several reviews of research on group composition have appeared over the years, but for present purposes, a paper by Moreland and Levine (1992) seems especially useful.

In that paper, Moreland and Levine argued that all research on group composition can be organized along three broad dimensions. First, different characteristics of group members can be studied. Some researchers study the size of a group, noting the simple presence or absence of members. Other researchers study the kinds of people who belong to a group, focusing on their demographic characteristics (e.g., age, race or ethnicity, gender), abilities (e.g., knowledge, skills), opinions (e.g., beliefs, values), or personalities (e.g., traits, motives, neuroses).

Second, the characteristics of group members can be measured in different ways. Some researchers use measures of central tendency, such as the mean level of a characteristic among group members (for continuous qualities) or the proportion of group members who possess a characteristic (for categorical qualities). Other researchers use measures of variability and thus assess the level of diversity in a group, or compare groups that are heterogeneous with those that are homogeneous. And a few researchers measure special configurations of characteristics in groups. Kanter (1977), for example, studied the problems that can arise in groups containing token members, and some researchers (e.g., Felps, Mitchell, & Byington, 2006) have recently become interested in whether and how one “bad apple” can affect a group.

Finally, different analytical perspectives can be taken toward group composition. Some researchers have viewed group composition as the consequence of certain social and/or psychological processes. Sociologists, for example, have focused on the impact of various external factors, such as shared memberships in social networks, or participation in common activities, that bring people into contact (Feld, 1982; McPherson, Popielarz, & Drobnic, 1992; Ruef, 2002). In contrast, psychologists have focused on the impact of various internal factors, such as commitment, that can lead people to enter or leave certain groups and groups to accept or reject certain people (Moreland & Levine, 1982; Schneider, 1987). Other researchers have viewed group composition as a context that moderates the operation of various psychological processes. Zajonc and Markus (1975), for example, argued that the intellectual development of a child is shaped by the “intellectual environment” of his or her family, as reflected in the average mental ability of all family members. Most researchers, however, have viewed the composition of groups as a cause for other phenomena, such as group structure, dynamics, and performance. Barrick, Stewart, Neubert, and Mount (1998), for example, measured both the abilities and personalities of work group members in various ways (the minimum, maximum, and mean score and the variance in scores), and then used those measures to predict several group outcomes (cohesion, viability, and performance).

A Generic Model of Group Composition Effects

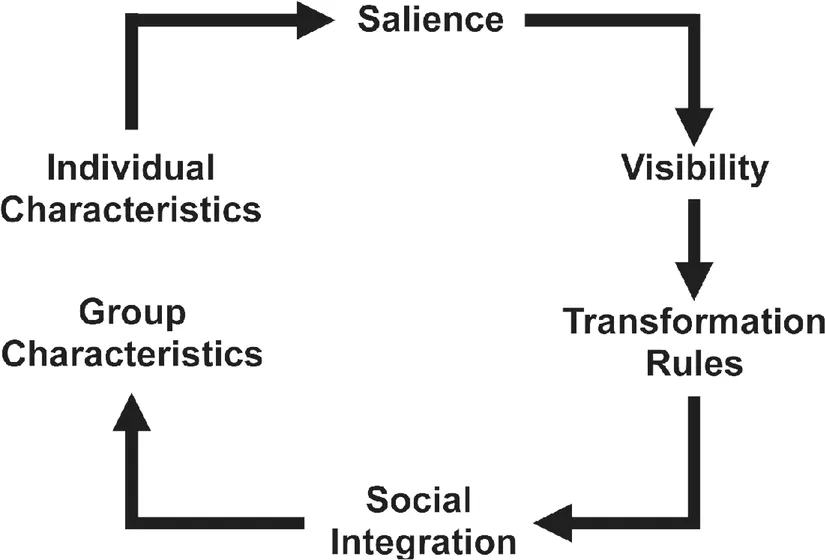

This last analytical perspective was the main focus of Moreland and Levine's (1992) papen One drawback of the research they reviewed was that researchers tended to focus on just one or two individual characteristics, ignoring theory and research on other characteristics, even when they were likely to display similar effects. Moreland and Levine (see also Moreland, Levine, & Wingert, 1996) thus developed a "generic" model of group composition effects that would be applicable to any member characteristic. That model is shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 A generic model of group composition effects (Moreland & Levine, 1992).

The figure describes the transformation of individual into group characteristics, a complex process in which several variables play a part. The first of these is salience, which varies from one individual characteristic to another. Salience determines which characteristics (among all of those that group members possess) are likely to be transformed. Certain characteristics, such as gender or race, are naturally more salient than others, and thus will produce stronger composition effects, at least until group members have interacted enough to discover the other characteristics (e.g., abilities, opinions, personalities) that they possess (cf. Harrison, Price, Gavin, & Florey, 2002). Another factor that can affect the salience of a characteristic is its distribution within a group. Several theorists, especially Mullen (1987), have argued that a characteristic attracts more attention as its variance increases. For example, gender becomes more salient as the proportions of males and females in a group diverge (Kanter, 1977). This suggests that more heterogeneous groups will display stronger composition effects. Finally, a characteristic can become salient when it seems relevant to group members’ outcomes or lends meaning to their experiences (Oakes, 1987; Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004). What can make a characteristic relevant or meaningful? The answer depends on situational factors (e.g., the type of task on which a group is working) that direct group members’ attention toward particular characteristics and on personal beliefs among group members about which characteristics are most relevant to a given situation. This suggests that when a situation is highly structured, so that its meaning is clear to everyone in a group, or the group’s members come from similar backgrounds and thus interpret the situation in similar ways, a narrower range of composition effects will occur and those effects will be stronger.

When an individual characteristic is salient, composition effects involving that characteristic will occur. Every member of a group is likely to possess some level of the characteristic, but everyone may not contribute equally to any composition effects. Visibility, or the extent to which someone’s characteristics are noticed by other group members (Marwell, 1963), is an important variable. Visibility varies from one member of a group to another and several factors could influence a person’s visibility. For example, people who participate more often in group activities should have more impact on a group, because their characteristics are more visible to other members. And visibility should be correlated with status. For example, Schein (1983) claimed that groups often reflect the characteristics of their founders, and leaders’ characteristics may have more impact than those of followers on their groups (see Haythorn, 1968). Seniority could increase a person’s impact as well, because someone who has been in a group longer will be more familiar to its members. Finally, situational factors, such as the kinds of tasks a group performs and the relationships between its members and outsiders, could affect visibility. When a work group participates in an outdoor team-building exercise, for example, someone who has military experience may gain visibility because he or she possesses (or is believed to possess) relevant skills. And when a local sports team needs new uniforms or equipment, someone who has a wealthy relative, or a friend who works for a company that manufactures sports products, may gain visibility as well.

Finally, how do individual characteristics actually combine to affect a group? That is, what rules govern the transformation of individual into group characteristics? Two rules have been identified, although others may exist. According to the additive rule, the effects of individual members on a group are independent. This rule implies that a person will affect every group to which he or she belongs in the same way. The additive rule thus reflects a rather mechanistic view of groups. According to the interactive rule, however, the effects of individual members on a group are (to some extent) interdependent. This rule implies that a person will affect every group to which he or she belongs differently, depending on who else belongs. The interactive rule thus reflects a more organismic view of groups. When the interactive rule is operating, the transformation of individual into group characteristics is more complex and can thus be difficult to understand or predict (Larson, 2010). The special “chemistry” that occasionally occurs in groups can be interpreted as evidence of interactive composition effects.

When are additive versus interactive transformation rules likely to operate? A group’s level of social integration is the key factor. Moreland (1987) described social integration in terms of the environmental, behavioral, affective, and cognitive bonds that bind group members together. The more group members think, feel, and act like a single person, the more socially integrated they become. Composition effects that involve the additive transformation rule require little or no social integration, and so such effects are very common. Considerable social integration may be required for composition effects that involve the interactive transformation rule, however, so those effects are much less common.

Diversity in Groups

The main focus of this chapter is diversity and its effects on groups. In recent years, there has been a great surge in diversity research, primarily among organizational psychologists, who want to help managers cope with groups that contain an ever-greater variety of workers (see Friedman & DiTomaso, 1996). Many reviews of research on diversity have been published, covering literally hundreds of studies. (Some recent examples include Bowers, Pharmer, & Salas, 2000; Horwitz and Horwitz, 2007; Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003; Jehn, Greer, & Rupert, 2008; Joshi & Roh, 2009; Mannix & Neale, 2005; Van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007; Webber & Donahue, 2001; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998.)1 More reviews are likely to appear, because the problems of work group diversity are far from being solved.

Reviews of research on diversity’s effects vary widely in the amount and type of research that they cover and the ways in which that research is analyzed (e.g., narrative reviews vs. meta-analyses). Yet there is considerable consistency in the conclusions reviewers have reached. For example, they often agree that whereas diversity has negative effects on group processes (e.g., trust and cooperation, conflict, communication, and cohesion), its effects on group performance are ambiguous. Those effects have been described as “weak” and “inconsistent,” among other things. This is not to say that one cannot locate specific studies that reveal positive effects (e.g., Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Hambrick, Cho, & Chen, 1996; Hoffman & Maier, 1961; McLeod, Lobel, & Cox, 1996) or negative effects (e.g., Ancona & Caldwell, 1992; Zenger & Lawrence, 1989) of diversity on group performance. Rather, the problem is that both kinds of studies are readily found...