Chapter 1

Critical voices in an age of anxiety

A reintroduction to the fear of crime

Stephen Farrall and Murray Lee

When faced with writing an Introduction, or indeed any sort of overview of the fear of crime, one is immediately struck with two questions. The first is ‘where to begin?’ and the second is ‘is there anything left to say?’. We think that there is still plenty left to say about the creature which has become known as the fear of crime (and since we do not intend to attempt an overview of the field, we give the first question a bit of a body-swerve). Those hoping to find between the covers of this book a review of the relationship between the fear of crime and various socio-demographic variables, or looking for a ‘quick fix’ to issues of how to reduce the fear of crime for some or other government target will find themselves sorely disappointed. We make no apologies for this. Such is the generally repetitive nature of most research on the fear of crime that Hale’s review (drafted in the early 1990s and published in 1996) is still an excellent summary of the field. However, this collection, we hope, drives on the debates which surround the fear of crime. All of the chapters are written by people who have some considerable experience of researching and thinking about the topics at hand. Our ‘critical voices’ come from around the industrialised world and from a variety of perspectives and backgrounds (urban geographers, sociologists, psychologists, psycho-analytically-inspired criminologists, political studies, and so on). Yet each, in some way, challenges some of the basic premises of the field. We shall return to these voices and what they have to say presently, but before we do we want to locate the fear of crime both in terms of the shifting nature of the debates and in terms of its place in wider social and political processes.

Locating the fear of crime I: An example from the UK

Interest in the fear of crime has ebbed and flowed since it was first discovered in the 1960s (some, see Loo, Chapter 2, in this book and Lee 2007, may prefer the word ‘invented’). Initially, the fear of crime was viewed as legitimate topic of research, expressing as it appeared to a range of concerns about urban disorder in the US and rises in crime rates in the UK. Debates at this point focused on the seemingly strangely high levels of fear given the objectively low levels of risk. ‘Why were fear levels so out of kilter with risk levels?’, we asked ourselves. However, the tone of the debates changed, at least in the UK, from the 1980s onwards, as left realists and feminists waded into the field, questioning what crime surveys ‘did’ and what the fear of crime ‘meant’ and was ‘used for’. Some answered the ‘rationality question’ with a further question (along the lines of ‘what would a rational level of fear be, anyway?’, Sparks 1992) whilst others suggested that if one viewed levels of fear through the lenses of patriarchy and low level but enduring intimidation then the higher rates of fear for, amongst others, women, ethnic minorities and the urban working class, started to make sense. Following these debates, the UK’s Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC) commissioned a programme of research entitled Crime and Social Order. A number of the projects touched on the fear of crime (or as it was sometimes called ‘anxieties about crime’ or ‘public sensibilities towards crime’ – and some of those most centrally involved in that programme and its work as it pertained to the fear of crime are amongst our contributors).

The Crime and Social Order programme ended towards the end of the 1990s. Various of the projects which had explored the fear of crime ended on notes which suggested that the fear of crime was a confused and congested topic (which indeed, it was and still is). For example, Wendy Holway and Tony Jefferson (2000) pointed to the importance of making sense of individual biographies when exploring the fear of crime. Others, such as Evi Girling, Ian Loader and Richard Sparks (Girling et al. 2000:66) suggested that public sensibilities and ‘crime talk’ constitute ‘a means of registering and making intelligible what might otherwise remain some unsettling, yet difficult to grasp, mutations in the social and moral order’. This involves, they suggested, the use of metaphor and narrative about social change and the folding of stories, anecdotes, gossip, career, and personal biography together with perceptions of national change and decline. Yet others, for example the team lead by Jason Ditton, reported that they had pretty much lost faith in the then current survey measures used to explore the fear of crime (see Farrall et al. 1997 most notably). So, just as the Labour Party (or New Labour as they preferred to be called) came into office, academic criminologists in the UK dropped the fear of crime as a research topic and went off in pursuit of new toys. However, as Lee (2007) notes, despite the critical nature of this later qualitative turn, fear of crime had already become an object of intense governmental interest.

As academic research on the fear of crime in the UK pretty much dried up completely, so the fear of crime ‘industry’ switched homes; leaving academe and taking up residence first in central government departments before, like many approaching their forties, moving out to the provinces as part of a key plank in the Crime and Safety Audits inspired by the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (see also Lee, Chapter 3, in this book, for a review of the situation in Australia). If academics had appeared reluctant to engage with the fear of crime for methodological or conceptual reasons prior to this, there was now no way that many of them were going to get their hands dirty with the messiness of ‘delivery’. This is not to suggest, by any stretch of the imagination, that there are no UK academics prepared to ‘roll up their sleeves’ and put the concept to good (and critical) use, for some notable exceptions do exist. Betsy Stanko, now of the Metropolitan Police, but formerly well and truly of academe, is amongst the best known of UK-based researchers who has taken on this task, and of course, her work will be familiar to more than just British readers. Still, by and large, academic criminology in the UK has fallen out of love with the fear of crime.

We hope that, perhaps, this book can go someway towards reinvigorating academic interest in the topic – certainly if this collection of voices cannot inspire further research, it is hard to see what can. For while many contributors to this book might lament the invention of fear of crime as an organising principle for this body of research and literature, most would also be wary of it becoming the exclusive domain of an ‘administrative criminology’ conducted only in the service of government and government-inspired targets. To disengage with the debates now runs the risk of a poor organising principle, and a range of mediocre if not counter-productive methodologies, becoming even more ingrained. As we have seen with the development of this body of knowledge, time-series data can often become normalised in a way that reinforces its own truth value (Farrall 2004; Lee 2007).

Locating the fear of crime II: Where ‘is’ the fear of crime, what does it ‘do’?

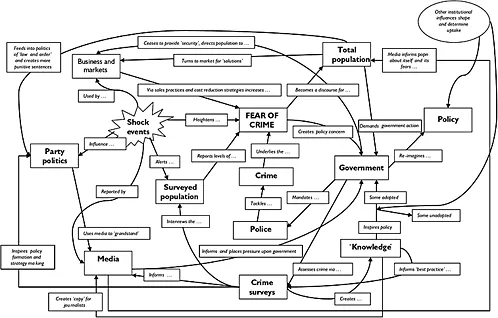

By posing these questions, we do not mean to embark upon a series of (frankly, quite tedious) paragraphs devoted to discussions of ‘hot spots’ of crime, ‘sink estates’ or to go through the houses on poorly-lit underpasses. Nor do we see ourselves initiating a review of the fear of crime as enforcer of after-dark curfews or of reducing levels of social cohesion (although, undoubtedly for some, it does have this effect). Rather, we see these (and similar questions) as a way into our own efforts to think through what it is that the fear of crime does to debates in contemporary societies and how it influences debates about ‘law and order’ (for want of a better term). We sketch these ideas out as Figure 1.1.

This figure attempts to describe the relationship(s) between the fear of crime (at the centre of the figure) and key political, social and economic organisations and institutions (in bold in the square boxes). The relationships are represented by the arrowed lines, and their operational characteristics described in italics in smaller square boxes.

Let us start not with the fear of crime, but with government. Governments initiate crime surveys in order to assess crime in their jurisdictions. This is partly because of a widening disillusionment with official crime statistics (which comes in part from ‘knowledge, that is academic and officially-approved versions of truth which point to the failings of such official crime statistics) and the media (which report such views). Having commissioned crime surveys, samples of the population are surveyed, and over time, the information gained from such surveys fed back to the media and the wider population itself (the ‘double hermeneutic’ as Giddens (1984) would have it, or the fear of crime feedback loop in Lee’s work, for example 2001). The surveyed population reports varying levels of crime fears (amongst other things, of course). Such fears become a discourse amongst the wider population for making sense of events (Girling et al. 2000) or for expressing other anxieties (Taylor and Jamieson 1998; Farrall et al. 2006), and also creates a pressure for the government of the day to ‘do something’ about crime. As well as placing pressure upon the government, the views of the populous (along with the data from crime surveys) are used by political parties to attune policies and encourage some to appeal to the electorate by making crime (and/or the fear of crime) an election issue. Survey data also, of course, assist in the formulation and reformulation of ‘knowledge’ and hence policy suggestions.

Figure 1.1 Relationship(s) between the fear of crime and key political, social and economic organisations and institutions

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the government is slowly moving away from its role as ‘provider of safety’, instead pointing citizens towards the market for solutions to crime and their fears (which the population, with its understanding of budget restrictions and their own responsibility, has little choice but to embrace). Businesses operating in this market, which is – like all markets – competitive, need to exploit such fears and anxieties in order to sell their goods and services (new credit cards which are ‘fraud-proofed’, new windows which are burglar-proof and such like, see Hardy 2006 on the motor cycle insurance industry). Such practices remind the population that it is ‘at risk’ and serve to heighten crime fears. Shock events (murders of ‘decent passers-by’, abductions of children, serious crimes against members of the public, unexpected rises in crime rates, etc.) are used by those operating in the market to ‘ram home’ their message, and in so doing such events both directly and indirectly increase fears by their usage by businesses, media reporting and political grandstanding.

‘Knowledge’ suggests to government various policies which could be pursued to tackle the fear of crime. Some of these are adopted, others are not. The reasons for the adoption or non-adoption of such policies is influenced by a range of institutional pressures. Some of these relate to cultural norms which are unique to each nation, its history, political colour and popular ideas (which influence both government officials and academics, of course) about the causes of crime. All of these will vary over time and are not in anyway static.

This fluidity of crime fear discourse, its diffuse and yet often intensely localised nature, is often lost in its attempted quantification – or at least in the way it has traditionally been quantified. If there is one theme that, perhaps, defines this book, it is this inclination to move away from a static enumerated reading of fear of crime and to see it in its socio-political, psycho-social and geo-spatial contexts. That is not to suggest that the contributors here have disengaged with quantitative methodologies; rather they engage with these in new and reflexive ways with intense critical reflection which takes account of the researchers’ own role in the production of knowledge. Reading this book will, no doubt, confirm that fear of crime is irreducible to specific ‘causes’, inherently political, discursive and yet intensely personal.

The collected essays

Our first essay is that by Dennis Loo. Loo takes us back to the 1960s, and to the US. Loo identifies the Republican Party’s desire to challenge the bedrock of values which had produced and been consolidated by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his New Deal programme and the notion of a Great Society under Democratic President Lyndon Johnson. Loo argues that ‘elites fabricated a fictive consensus around “law ‘n’ order” in the 1960s and employed it as a device to introduce momentous public policy changes’, directly challenging the notion that these changes in social values occurred naturally. In a telling passage, Loo argues that:

By combining several different items into a category created after the fact, Gallup created the impression that crime concerns were much higher than they actually were. Other polls publicised in the remainder of 1968 also either conflated categories, perpetuating the impression of more robust crime concerns than were actually justified by the data or particular polls were selectively presented in a manner that generated the same impression. The polls not publicised in 1968 actually revealed crime concerns were dropping.

The ultimate message of Loo’s essay, however, is that the Republican Party shifted the terms of the debates from social injustices to a focus on law and order, pollsters manipulated or selectively reported their results to reflect this shift, leaving the Democratic Party little choice but to follow the agenda as it moved. A similar, although, of course, not identical process was witnessed during the UK’s 1979 General Election campaign, when Mrs Thatcher (who won the campaign for the Conservative Party) spoke of citizens having the right to feel ‘safe in the streets’ (the central referent of a key measure of the fear of crime in many a crime survey) and needing ‘less tax and more law and order’ (see Farrall 2006).

Following from Loo’s essay, we turn to that by Lee. Lee’s aim is to ‘identify a range of obscured dimensions of knowledge and power in relation to the representation of data concerning public anxieties about crime’. Lee argues that the intensely political dimensions of the fear of crime (and the resulting data, of course) and the socio-cultural implications of this, are often overlooked by government or ‘administrative’ criminologists who, on the assumptions that this thing ‘exists’ and is ‘out there’ to be measured, tend to reduce debates about ‘fear of crime’ to technical arguments. This, Lee argues, ignores all of that work (see Lee 2001, 2007; Stanko 2000; Loo and Grimes 2004; Loo, Chapter 2, in this book) which suggests that the fear of crime is contingent – something of a category of convenience. To paraphrase Lee, we created the concept (of crime fears) and only then reflected on whether or not it might be the most appropriate organising principal for a body of social scientific knowledge. This, naturally, is not to suggest that there was no anxiety about crime prior to the 1960s, for certainly there was (Pearson 1983). Rather, it is that the term ‘fear of crime’ was not an organising principle. As Lee elsewhere has noted (Lee 2007), the term was rarely if ever used before 1965. That the enumeration of such fear which resulted from surveys indicated significantly high levels of fear – or whatever was measured – meant that it became a governmental problematisation. Of course, once the fear of crime was enumerated and had become an organising principal for a range of criminal justice and social policy targeting, it also became a staple object of criminological inquiry attracting research funding and becoming the topic for thousands of academic publications (Hale 1996; Lee 1999; Lee 2007; Ditton and Farrall 2000). Consequently, not insignificant resources were invested in the ‘new problem’ of the fear of crime. As such, and this is also connected to the previous point, fear of crime became political from the moment it was enumerated.

Recent evidence (as if further evidence were needed) of the politicisation of the fear of crime and the associated concept of ‘insecurity’ has stemmed from the attacks on the US in 2001. Our next two essays consider this topic in some depth. First of all we have Smith and Pain’s essay, in which they develop from two models of analysing fear – the everyday and the geopolitical – a third model of understanding the fear of crime. This is an approach which does not ignore global processes and events or attempts at political manipulation, and which accepts that outcomes at the rather more mundane or ‘everyday’ level, are not predictable, requiring that they ‘make space for resistance to fear and fear discourses in everyday life too’. Ultimately, they argue that we need to shift the emphasis from ‘authoritative, remote, top-down models of fear’ towards more nuanced and grounded approaches based on everyday realities and perceptions. In so doing, Smith and Pain highlight the entwined nature of globalised fears and the processes which underlie them. Their ideas on the immediate local everyday fears and anxieties that are already present in some people’s lives and the relationship of these to the wider world stimulates further thoughts about their connections.

Weber and Lee seek to ‘critically assess the use of fear as a governmental tactic which has been employed as part of a national...