![]()

1

THE HISTORY OF THE NEANDERTHAL

DISCOVERY

Mettmann, 4. September. In the neighboring Neander Valley, the so-called “Rocks,” a surprising discovery was made in recent days. During the breaking away of the limestone cliffs, which cannot be sufficiently lamented from the point of view of aesthetics, a cave was uncovered, which over the course of centuries had been filled with clay sediment. Upon digging out this clay, a human rib was found, which doubtless would have been unregarded and lost had not, fortunately, Dr. Fuhlrott of Elberfeld secured and investigated the find.

Site of find, fossil, and finder. This contemporary account of the discovery of the Neanderthal, later to be world famous, appeared in the Elberfeld newspaper on 6 September 1856. It seems rather paltry from a modern perspective. The first find of human fossils to be recognized as such was made in an era of technological and scientific upheaval. The Industrial Revolution had made its mark on Europe and the idea of evolution had already appeared. In 1758, a century before the find in the Neander Valley near Mettmann, the Swedish Christian and natural scientist Carl von Linné had classified human beings together with prosimians, monkeys, and bats in his hierarchy of mammal primates or “ruling animals.” His contemporaries were indignant. After all, ever since the Middle Ages the ape had been viewed as a devil-created mockery of humanity. So to place the human being, created in the image of God, on a line with apes bordered on blasphemy. A hundred years later, in 1858, Charles Darwin threw open the question of human evolution with a single remark in his Origin of Species: “Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.” A heretical sentence, which the first German translator of the work found so offensive that he did not translate it. Darwin’s hidden thesis (and that of his often-forgotten fellow fighter Alfred Russel Wallace) that humans, like all other living things, must be the result of an evolutionary process and not a unique divine act of creation, was revolutionary. Darwin himself first summed up his views on human origins in 1871 in his Descent of Man. In Germany, the zoologists Carl Vogt and Ernst Haeckel paved the way for the theory of evolution in scholarly circles. In 1863, Haeckel delivered a lecture in which he argued that there must have been a link, now extinct, between apes and humans. He named this “missing link” Pithecanthropus alalus—“non-speaking ape-man”—and foretold that the fossil remains of this ancestor would be found in southeast Asia. Haeckel’s prophecy about the place of discovery would be fulfilled.

The origin of humanity has never been discussed with complete objectivity, since of course it is an issue that touches all human beings and is closely linked to ideological and political interests. Many regarded the extension of the human family tree into the animal kingdom as scandalous. As the bishop of Worcester’s wife is supposed to have said after a conversation with Darwin’s supporter Thomas Henry Huxley in 1860: “My dear, descended from the apes! Let us hope it is not true, but if it is, let us pray it will not become generally known.” Neither the fervent hope of the pious bishop’s wife nor the 1812 pronouncement of the French natural philosopher Georges, Baron de Cuvier, that “fossil man does not exist” kept fossil humans from winning recognition. The Neanderthal discovered in 1856 provided the first “living” evidence.

The Neander Valley near Mettmann, the discovery site of the first fossil evidence of primordial humans, was named after the Bremen theologian and hymnographer Joachim Neumann (composer of “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty, the King of Creation”). As was fashionable in 1670, he used the Greek translation of his name, “Neander” (Newman), in compliment to antiquity. Joachim Neander, at that time rector of the Düsseldorf Latin School, visited the “Rocks,” as the area was called then, seeking inspiration from the mountains, crags, streams, and cliffs “with a special amazement.” Whole generations of painters from the Düsseldorf Academy did the same. The Neander Valley became a locale for seeking the muses, a place of lyric poetry, sketches, and watercolors. It was doubtless the picturesque limestone cliffs and mysterious caves along the course of the Düssel River that enticed artists and town-dwellers to the “Rocks” (also called “Dog’s Crag” locally), only two hours distant by coach. Countless excursion groups sent couriers to the nearby guesthouses to order the proprietors “to have trout for 25 people ready, and also to lay in a supply of fresh butter and bread,” so that, strengthened by a good meal, they could wander in the valley.

The picturesque limestone cliffs between Erkrath and Mettmann were formed in the Devonian Age, between 360 and 410 million years ago. At that time, a shallow, tropically-warm sea covered the area that is now central and southern Europe. Clay and sand were repeatedly washed into the sea and laid down layer by layer. Coral reefs developed that, with the remains of their former occupants (lime-containing shells), created enormous chalk layers over the course of millions of years, finally hardening into limestone. These layers were covered over with slate. Finally, more clay and sand were washed into the sea from the land during the later Devonian Age, destroying the coral reefs’ habitat. In the following Carboniferous Era (360–290 million years BP [before the present]), tectonic plate movements pushed the limestone up through the slate layers above it. The limestone cliffs became solid land; their surface eroded and was cleared away by natural processes like rain and wind. Less natural was the demolition carried out by humans millions of years later. This landscape of cliffs and caves, where the study of primordial humankind (paleoanthropology) was born, has now to a large extent vanished.

In less than fifty years a limestone quarry that was opened in the region destroyed the picturesque valley and its gold-white limestone cliffs and caves. Johann Carl Fuhlrott, the first preserver of the Neanderthal bones that two quarry workers found in 1856, both lamented and welcomed this circumstance in his first description of the fossils:

When the bones were uncovered, the credit for keeping them from being dumped into the Little Feldhof Grotto along with the limestone rubble goes to Wilhelm Beckershoff, owner of the quarry in the Neander Valley. Guided by a hunch that what had been found were the fossil bones of cave bears, he had the fragments collected from the loose rubble. At that time, fossil animal bones were no longer a novelty. Johann Heinrich Merck of Darmstadt, a good friend of Goethe, collected, described, and reconstructed fossil animals. And the Bonn geologist Johann Jakob Noeggerath, who visited the Neander Valley and its cave-filled landscape, wrote:

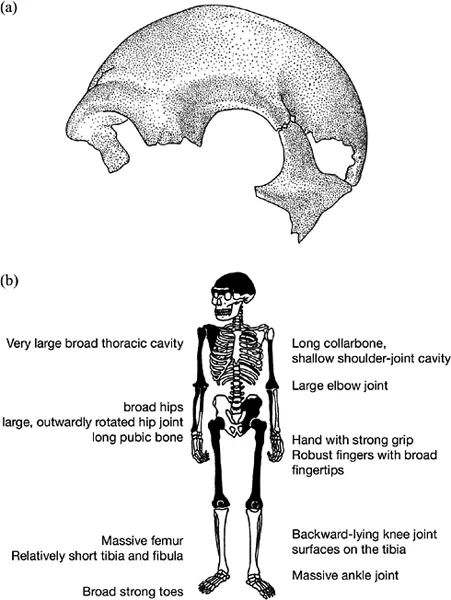

As prophesied by Noeggerath, it became clear how fortunate the quarry-owner Beckershoff’s find was when his partner Friedrich Wilhelm Pieper gave the bones to the zealous fossil collector Fuhlrott. Fuhlrott, a teacher in Eberfeld, was a child of his age. He knew about the latest findings in the new sciences of geology, archaeology, and paleontology, and did not hesitate long with his assessment. He labeled the bones that had been given him as supposedly those of cave bears—a skull cap, a fragment of a right shoulder blade, a right clavicle, as well as right and left humerus, two ulnas, a radius, five rib fragments, the left half of a pelvis, and two femurs—as unequivocally human (Figure 1).

Stimulated by the sketchy media report about the early humans, who must have belonged “to the race of the flat-heads, who still live today in the American West,” two Bonn anatomy professors contacted Fuhlrott. These men, Hermann Schaaffhausen and Franz Josef Carl Mayer, were curious about the discovery and asked Fuhlrott to send them the precious bones. Fuhlrott kept the two scholars dangling for a bit, then traveled to Bonn himself, carrying the Neanderthal in his luggage, carefully packed in a wooden chest. Mayer, sick in bed at the time of Fuhlrott’s visit, missed the first scientific encounter with the Neanderthal. Nonetheless, the fossils found themselves in good hands with Schaaffhausen. He himself had already written an article, “On Stability and Change in Species,” in 1853, in which he discussed the existence of fossil humans. Only six months after this first appraisal, on 2 June 1857, Schaaffhausen and Fuhlrott presented the discovery to the scholarly world. Those who attended this meeting of the Natural History Society of the Prussian Rhineland and Westphalia witnessed a major historical moment. In his essay “Human Remains from a Cliff Grotto in the Düssel Valley,” published in 1859, Fuhlrott achieved a remarkable contribution to research on the existence of fossil humans.

The discovery would not let the teacher rest. Thus, two years after the bones were uncovered he again asked the workers about the exact site of the find. It emerged that the fossil-bearing clay layer in the Little Feldhofer Grotto was about 1.5 to 1.8 meters thick and that it was therefore likely that the entire skeleton lay about half a meter below the surface of the sediment, with its head toward the cave’s entrance. The published data included precisely described anatomical peculiarities in the find, such as the unusually heavy bones and brow ridges, “which were completely joined in the middle.” The editors of the society’s proceedings commented in an afterword that they “cannot share the reported opinions.” Fuhlrott ended his essay interpreting the Neanderthal as an ice-age “primitive member of our race” with the statement that he would gladly renounce “every attempt at propaganda” to convince “and leave the final judgment about the existence of fossil humans to the future.” But the German scholarly community had apparently reached its negative judgment long before this point.

THE NEANDERTHAL AS OBJECT OF SCHOLARLY CONTENTION

Schaaffhausen provided exact anatomical descriptions and suggested that the massive bone development of the unique fossil skeleton, perhaps dating to the Diluvian Age, gave evidence of impressive muscular development that in turn hinted at the arduous life circumstances of these raw and wild early Europeans. The influential anatomist and pathologist Rudolf Virchow, an opponent of evolution, took the opposite position in the debate over primitive humans. He personally viewed the original bones in 1872, having previously left their examination to Franz Josef Carl Mayer, Schaaffhausen’s colleague in Bonn and a crucial supporter of the Christian creation doctrine. Mayer affirmed the Neanderthal’s rachitic bone deformations, which established, according to Virchow, that he must “have walked only in a somewhat grotesque manner.” Mayer asserted, among other po...