Chapter 1

Neo-Feminism and the Rise of the Single Girl

Explicitly and implicitly, women are instructed by their environment (from the school room to the women’s magazine) in how to “become” a woman—a task that is never completed and is subject to constant revision.1 This concept of identity as a process of “becoming” has been understood as offering emancipatory possibilities to the individual who is invited, not to take up a stable, untested and fixed position, but, rather, to see her “self,” or even “selves,” as subject to a multiple and on-going process of revision, reform and choices.2 The development of contemporary culture, however, beginning with the rise of consumerism and the concomitant cultivation of the body and self-presentation, exploits the idea of the “becoming woman” for the purposes of consumer industries. As a result, it is difficult to maintain an entirely optimistic view of this system of unstable identities, which capitalism encourages, rather than discourages.3

In 1992, sociologist Robert Goldman used the terms “neo-feminism” and “commodity feminism” to describe the ways in which advertisers suggested, in the 1970s and 1980s, that “control and ownership over one’s body/face/self, accomplished through the right acquisitions, can maximize one’s value at both work and home.” He maintains that “[a]s far as corporate marketers are now concerned, this new ‘freedom’ has become essential to the accumulation of capital—to reproducing the commodity form.”4 Following upon analyses like that of Goldman, I propose to use the term “neo-feminism” to refer to the tendency in feminine culture to evoke choice and the development of individual agency as the defining tenets of feminine identity—best realized through an engagement with consumer culture in which the woman is encouraged to achieve self-fulfillment by purchasing, adorning or surrounding herself with the goods that this culture can offer. Choice, particularly in the form of “shopping,” as a process of weighing and evaluating alternatives with a view to making a decision that optimizes the individual’s own position, is the fundamental principle that governs neo-feminist behavior.5

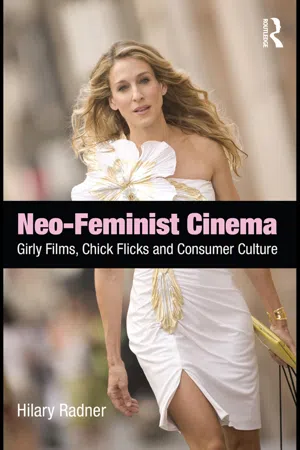

Neo-feminism, then, can be understood as a set of practices and discourses that define a certain position or “identities” (that women may or may not take up) that have developed in the post-World War II period in the United States and in Western Europe. The topic that I wish to explore here is the discursive formation that arises out of this development in the evolution of feminine subjectivity, particularly in the way it informs a spate of films that I call “girly” films, using the term girly for two distinct reasons.6 The first is to suggest how “girlishness” and “girl” have been reclaimed by feminine culture as a new ideal promising continual change and self-improvement as a sign of individual agency (a girl is always in the process of “becoming”). Second, the term underlines ways in which the sexual availability of women, represented by images initially addressing a male viewer, as in the girly magazines of the 1940s or 1950s, has been rewritten as a form of personal empowerment. The girly films form a distinct class of cinematic narratives, regularly released over the last 20 years, that reproduce a neo-feminist paradigm aimed at women audiences, falling into the category “chick flick,” without exhausting it. While all girly films sit comfortably within the category “chick flick,” not all “chick flicks” are girly films, nor do all “chick flicks” reproduce a neo-feminist paradigm. It would be difficult, however, to find a single popular film made after 1965 that has not been influenced by this neo-feminist position—or rather, the sets of discourses and practices that inform it.

The various discursive practices involved all concern contemporary feminine identity—in Stuart Hall’s terms, “not ‘who we are’ or ‘where we come from,’ so much as what we might become, how we have been represented and how that bears on how we might represent ourselves.”7 For Hall and other cultural-studies scholars, “identity” in the form or a “self” or “selves” is a necessary heuristic device—not simply for scholars, but also for the subject, who must fashion a “self” in order to perceive, understand and act.8 This does not mean, however, as Hall explained in an oft-quoted article, that the self is an invention by a particular individual; rather, “selves” have a “discursive, material, or political effectivity.”9

My interest in the girly film as a particular representation of neo-feminism stems from the manner in which this cycle of films underlines the inherently fissured and contradictory nature of the discursive formation that it invokes. In a 1974 article commenting on classical Hollywood cinema, film scholar and theorist Dana Polan remarks: “[b]ourgeois existence is often little more than a continual succession of disappointments, of subversions, all of which fissure our self unity and social unity as acting subjects.” For Polan, popular art-forms hold a privileged relationship with the “self-unity and social unity” of a given subject—which is not to say that this unity is homogeneous, but rather that it is itself a facet of identity as a process of self-revision. In the same article, he comments that “texts … are contracts in which spectators or readers willingly agree to relate to codes in a certain way … with knowledge usually of the workings of many of these codes.” Polan also underlines the fact that transgressions of the code—the production of contradiction and critique—are “inherent in the system.”10 The girly film, being a discursive form that depends upon both shared codes and their transgression, displays the inherently vexed nature of femininity that both feminism and neo-feminism imply for the feminine subject in contemporary culture.

Fundamental to this analysis is an assumption that feature-length films provide a particularly dense articulation of the contemporaneous discursive formations in which the film participates—formations that it may reproduce, modify and critique.11 In contrast with television programming, women’s magazines, blogs, or other popular-culture forms, the feature-length Hollywood film characteristically condenses the terms that define a given formation in order to amalgamate them into a single representation of a finite duration. While film and television (as opposed to the blog) share a mode of production depending upon a deep division of labor, the feature-length film, as a lynchpin element in a system of media synergies, constitutes a privileged cultural form in terms of capital investment as well as labor. Consequently, these films offer highly schematic representations of both the codes, and the transgressions of these codes, that define neo-feminism. Scrutinized by marketing experts, the popular Hollywood film may well provide a “royal road” to the collective drives, conscious and unconscious, of its audiences, its desires and fears, in so far as these can be made to coincide with the tenets of the consumer-culture orientation of the medium itself. Because the neo-feminist paradigm encourages and reinforces consumer culture practices, it constitutes a very attractive—and hence often exploited—version of feminine identity, from the perspective of Hollywood.

The term “neo-feminism” has been used sporadically and somewhat impressionistically in a variety of ways since the 1970s, having in common the assumption that neo-feminism is a reaction to feminism, in particular second-wave feminism. A 1998 manifesto claimed “neo-feminism” as the antidote to post-feminism, focusing on “choice” and individual fulfillment. These self-proclaimed “neo-feminists” reject certain forms of consumer culture, as did third-wave feminist Naomi Wolf, but share her focus on the individual and individual fulfillment. “Neo-feminism” is a term also used in opposition to “state feminism” in the discussion of Soviet bloc countries. Again, the term suggests a turning away from political reform. Similarly, neo-feminism also appears from time to time to characterize any kind of wrong turn in feminist thought, as in the case of Margaret A. Simons, who describes as “neo-feminist” the trend in French feminist thought that sought to replace Simone de Beauvoir’s rationalist (and hence masculinist) feminism (moving towards the erasure of gender difference) with a glorification of the feminine, frequently referred to as essentialism. These perspectives have in common the assumption that neo-feminism is a reaction to feminism, in particular second-wave feminism.12

Most notable are feminist literary critics, who have tended to locate “neo-feminism” as an outgrowth of feminism, manifested most clearly in novels in which the heroine, in the words of Ellen Morgan, writing in 1978, “is a creature in the process of becoming … struggling to throw off her conditioning and the whole psychology of oppression.”13 Kim Loudermilk, for example, writing in 2004, associates “neo-feminism” with third-wave feminists such as Naomi Wolf, because of Wolf’s emphasis on individual choice as the solution to women’s oppression, in particular through her critique of the feminist positioning of women as “victims.”14 Loudermilk traces the development of “fictional feminism,” a form of feminism propagated by novels, and to a lesser degree cinema, which she claims “recuperates feminist politics, containing any threat that feminism poses to the dominant culture.”15 The novels and films that she considers, such as The Handmaid’s Tale, or The Witches of Eastwick,16 engage explicitly with the representation of feminism in ways that undermine a contemporary understanding of the goals of second-wave feminism. Where I take issue with scholars such as Morgan and Loudermilk is the manner in which they see second-wave feminism itself as the origin of these neo-feminist tendencies in contemporary culture. I argue that neo-feminism, while arising out of the same social conditions as feminism, and sharing some ambitions of second-wave feminism, such as affirming the need for financial autonomy for women, had significantly different goals—goals that coincide not with the reformist agenda of second-wave feminism, but with the individualist and rationalistic agenda of neo-liberalism.17 In part, what provokes Morgan’s and later Loudermilk’s reactions to what Loudermilk calls “fictional feminism” is not simply the co-option of feminism, but also the rise of neo-feminism, which did indeed deftly turn many of feminism’s reforms to its advantage, while being motivated by principles of self-interest.

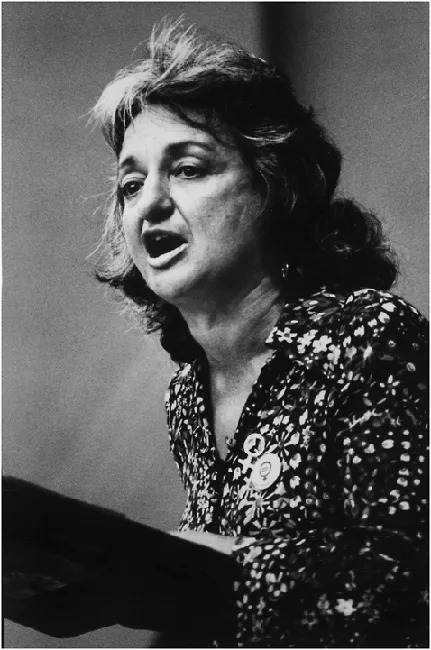

Second-wave feminism is represented by activists like Bella Abzug (1920–98) or Betty Friedan (1921–2006), middle-class educated women, as a whole “white”; these last were inspired by ethical imperatives to take up the cause of women and become her political voice, with the aim of achieving political and institutional reform within a traditional definition of a civil society, which they sought to enlarge (see Figure 1.1). While second-wave feminism did advocate a program of self-fulfillment, it did so within a climate of social responsibility and state intervention. Individual fulfillment was meaningless outside the policy of larger social and institutional change. Characteristic of this position (which remains a crucial dimension of contemporary feminism) is that of Barbara

Ehrenreich (b. 1941), feminist activist and writer, who, in 2002, exhorts her readers to seek “activist solutions” to the plight of “migrant women engaged in illegal occupations such as nannies and maids.” Ehrenreich and her co-author Arlie Hochschild (b. 1940), another longstanding feminist, urge their readers “to consider these women as full human beings. They are strivers as well as victims, wives and mothers as well as workers—sisters, in other words, with whom we in the First World may someday define a common agenda.”18

In contrast, the preoccupation of neo-feminism is the individual woman acting on her own, in her best interest, in which her fulfillment can be understood as independent of her social milieu and the predicament of other women as a class that crosses international boundaries. As a largely pragmatic set of behaviors and principles, neo-feminism seeks to provide a means of survival and success for the woman who, without family or other sources of material support, counts her own body and the work that it performs as her principle resource. Though neo-feminism can be said to challenge patriarchal structures, it does so in the name of capitalism, in which allegiance to family, for example, has little significance within an economic field. The subject is a free agent working in his or her own interests with a view to optimizing his or her position outside of the confines of family and hereditary status, but within a profit-driven society.

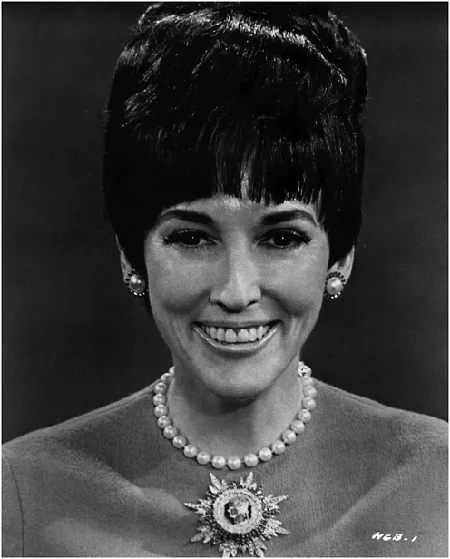

Crucial to the establishment of the neo-feminist paradigm in the 1960s and 1970s was the emergence of the single girl as a feminine ideal, exemplified by Helen Gurley Brown (b. 1922) as a media icon, as well as through her various publications, beginning with Sex and the Single Girl in 1962 (see Figure 1.2).19 The single girl achieves her identity outside marriage and, significantly, does not define herself in terms of maternity. Both in appearance (waif-like and adolescent) and in goals (to be glamorous, adored by men and financially independent), the single girl, for whom sexual pleasure is a right, defines femininity outside the reigning patriarchal construction based on marriage and motherhood. At the same time, the single girl is defined through consumerism—in particular, her capacity to function as a knowledgeable acolyte of feminine consumer culture. One of the significant traits of the neo-feminist paradigm is the way in which consumer-culture glamor replaces the maternal as the defining trait of femininity. While the neo-feminist paradigm does not preclude maternity, as the recent vogue for “yummy mummies” demonstrates, it displaces the centrality that it held, for example, in the early twentieth-century and nineteenth-century accounts of feminine self-fulfillment.20

Fueled by the ever-increasing need of consumer industries for new markets, popular culture encouraged the emergence of discourses presupposing that fulfillment of an individual’s needs and desires is an expression of good citizenship and, paradoxically, the sharing of a common culture. This discourse

encourages the individual to realize his or her self in the pursuit of pleasure— a pleasure that is first and foremost sexual—with individual gratification being the final expression of the citizen’s inalienable right to the pursuit of happiness. In this articulation, popular culture posited the personal rather than the political as the primary arena of experience and citizenship. Although the formula “the personal is political” came to characterize the new feminist values of the 1970s and 1980s, this neo-feminist position, far from challenging consumer culture, affirmed its continued attempts to collapse the public and the private, to eliminate the public sphere as the forum of a specifically political e...