Becoming an actress

I realised that I was an actress after writing this profession in my passport. I had already been working for a few years at Odin Teatret, the Danish theatre group founded in 1964. As a teenager I never contemplated becoming an actress, a job I associated with falseness. I was shy, it was hard for me to speak in public and I would never have imagined myself on a stage.

A film I saw when I was ten is the first memory I associate with theatre. It was projected in a theatre in Milan that usually showed English-speaking comedies. It gave me a pleasant feeling. It told the story of a group of shipwrecked children and their adventures on an island. A year later, my grandmother took me to see my first real theatre performances. In London I saw Rudolf Nureyev dance and I watched a matinee of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I counted the times Nureyev crossed his legs when he lifted off the floor in a leap that seemed eternal, while in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, performed in a park, I enjoyed seeing the characters appear from behind trees. I knew of Shakespeare from a children’s book in which his tragedies had been given happy endings; when a few years later I saw Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet, I filled a whole scarf with tears as I did not expect the sequel of suicides.

Survivors on islands, physical activity and actors in the open air: these first images of theatre reappear today in my actress’s work as reality, constriction and necessity. The floating islands of the Third Theatre, training and performances in unusual places, are nowadays recognised as part of the variegated world of theatre. However, to get in touch with them, I had first to replace the sensation of falseness I associated with the theatre profession, as presented on television and in magazines when I was a teenager, with the concreteness that becoming an actress would demand of me.

The first place I worked with theatre was a garage in Milan. Three times a week Teatro del Drago rehearsed there, after removing the cars. The floor was dirty with oil. Our costumes consisted of jeans and blue t-shirts. The group had started a year earlier with some students gathered by Massimo Schuster, an Italian who had worked with the Bread and Puppet Theater in the United States. Bored by my school and its slowness and lack of challenge, I had joined an evening class in German to use my time in a better way. There, one of my classmates spoke about underground theatre. The word underground caught my attention: in those days, in Italy, political terms were more fashionable. It was November 1972 and I was eighteen years old.

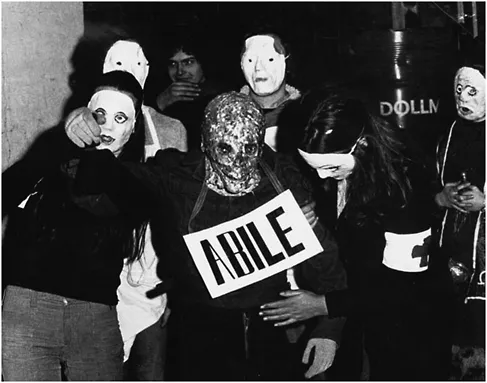

I watched Teatro del Drago’s rehearsals one evening, returned another day and was immediately included in a scene: I was a nurse in a staging of Bertolt Brecht’s poem, The Dead Soldier. We wore masks, which helped me hide my embarrassment and the feeling of being totally ridiculous. Theatre seized me without waiting for me to choose it. I was attracted by the garage, the people and their commitment: there was rebellion in the air without time-wasting discussions. There I met Marco Donati and Clara Bianchi.

In order to take part in rehearsals on Tuesday and Thursday evenings and Sunday mornings, I had to give up athletics, volleyball, riding and skiing at the weekends. However, these same sport activities provided the first basic knowledge for my theatre craft.

The skiing competitions taught me the importance of preparation: the trainer made me study all the gates of the race by climbing up the mountain with my skis on, following the course in reverse. I needed to be familiar with all the

angles, bumps and sheets of ice in order to be able to ski down without hesitation and with complete concentration. My gymnastics teacher explained that I should never think of the race ending at the finish line, but imagine it continuing much further. This would avoid a reduction in speed caused by believing the end was in sight. I was the volleyball team captain at high school. Awareness of being part of a group and the cooperation of each single team member were essentials to winning. I had learned this when we managed to turn a game around in our favour after I had encouraged my fellow players during a break. At fourteen and fifteen, I spent my summer holidays teaching smaller children to ride. I was not an excellent rider, but the responsibility for guiding others taught me to show self-confidence.

With my friends of Teatro del Drago, I saw 1789 by Théâtre du Soleil in Paris. This performance, directed by Ariane Mnouchkine, changed my vision of what theatre could be and, still today, is an important reference. For the first time I experienced promenading spectators (who personified revolutionary masses and a market crowd) encircled by actors. We had walked to the theatre in the morning along the Bois de Boulogne, to try to get tickets for the sold-out evening performance. It was the Christmas holidays; we lived three to a room in a hotel used by prostitutes and we had no money. Ariane Mnouchkine, who was busy working on her film Molière, despatched us to the box office with an instruction to give us free tickets. Two years later, Teatro del Drago was invited to a festival of anti-military performances by another company from the Cartoucherie in Paris, and I could see how the Théâtre du Soleil had been transformed completely for L’Age d’Or.

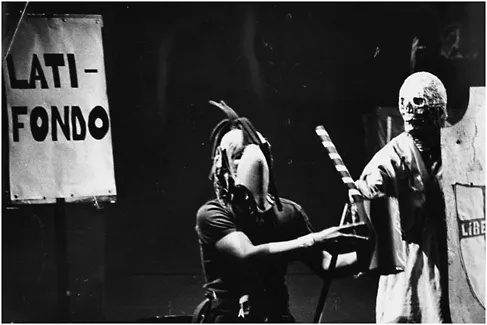

Teatro del Drago split up after an internal argument: I was no longer part of an underground theatre, but of a political one. I had been an anarchist and then an activist of Avanguardia Operaia (workers’ avant-garde), one of the groups of the revolutionary Left in Milan. In those years, 1972–6, making theatre was my way of participating in the students’ and workers’ struggle. In the time off from Teatro del Drago’s political duties and the making of masks and puppets, we asked ourselves how we, as people who presented performances and made theatre interventions, should prepare. We wanted our theatre to be useful and inform by entertaining. The word actor was not a part of our vocabulary. There were no directors. We accepted leaders and positions of responsibility in political parties and in grass-roots organisations, but in theatre we were unruly radicals. Marco Donati, one of the founders of Teatro del Drago, was more effective on stage than others, but this did not give him the right to make decisions.

We had moved from the garage to a cellar, then to a political collective’s meeting place and finally to a squat in Via Santa Marta in the centre of Milan. Here we opened a theatre, music, design and film school as part of the activities of the Circolo La Comune, an organisation originally set up to support Dario Fo’s and Franca Rame’s performances. Before each rehearsal we would clear away the chairs that cluttered the space after the meetings and empty the ashtrays. Hundreds of young people attended the courses. One of them was Claudio Coloberti, who was to become a member of Teatro del Drago. I organised workshops and classes, contacted professionals, taught, wrote leaflets and press releases, prepared festivals, moulded masks, acted in performances wherever we were called, drove our old blue van, got in touch with journalists and trade unionists, entered discussions, called and presided over meetings, took part in the courses, recycled clay, painted the walls of the squat … I worked in the morning to earn money, in the afternoons I went to university and in the evenings and at night I did everything else. Enthusiasm, passion, political belief, deep convictions, little rest, no money, meetings and more meetings, assemblies, protest marches, community fêtes … were my daily bread.

Although I showed my colleagues some gymnastic sequences to use as a warm up, we were taught our first real theatre exercises by members of La Comuna Baires, an Argentinian theatre group exiled in Italy, and by Teatro del Sole, a Milanese company that made children’s theatre. We exercised each part of our body separately, moved our shoulders and hips, and played with an imaginary ball throwing it with an impulse from different parts of our bodies. We did forward and backward somersaults, over and under tables, jumping over people and chairs, overcoming our fear. We called it physical expression. During an exercise, I walked with my eyes closed, smelling and touching objects in various parts of the room. In another, I ran happily in a circle, while someone on the outside gave directions to make us change the position of our arms.

The streets, universities, factories, neighbourhoods, markets and community fêtes were our real school. We would arrive in our old van with English number plates – my father had given it to us after winning it at backgammon – unload our props and present the performance. If we were lucky they would give us 50,000 lire, which, at that time, would just about pay for the petrol.

One of our performances condemned the 1973 military coup in Chile. Wearing a death mask made of wax, I represented the political party of the Christian Democrats. During a stage action called Carillon, which showed the links between the industrialists of various countries, I wore a bowler hat. In an anti-war performance, I was dressed as an American marine. During the campaign for the referendum on divorce, I carried bride and groom puppets with the faces of Almirante and Fanfani (two conservative Italian politicians) dressed in a rubbish bag and the bridesmaid’s dress I had worn at my aunt’s wedding when I was six.

We took part in protest marches using big masks that we constructed especially for each occasion. At an anti-imperialist demonstration I was inside a giant paper tiger; on the march for the right to work I walked in front of a four-metre-high red cloth elephant.

I saw Odin Teatret for the first time on television. My comrades of Teatro del Drago, Santa Marta Social Centre and Circolo La Comune were with me. The programme presented various ‘barters’ carried out by Odin Teatret in the villages of Salento in southern Italy. We were sure our world would interest them. Mela Tomaselli and Luciano Fernicola, collaborators from our theatre

school, had already been in touch with this Scandinavian group. They went to Pontedera, where Odin Teatret was on tour, to invite some of the actors to give a workshop and suggest a barter with us when they came to Milan.

Torgeir Wethal, one of the founders of Odin Teatret, came to Santa Marta. Two other actors, Tage Larsen and Tom Fjordfalk, went to Isola, a social centre with which we had joined forces in order to host Odin Teatret, who had been invited to Milan officially by CRT (Centro di Ricerca per il Teatro). We discussed at length how to organise the workshops and choose the participants. We asked ourselves whether it was right to accept the availability of the mythical Nordic actors during the day, when we considered ourselves workers who made theatre only at night.

I heard of theatre training for the first time. Torgeir guided us in the development of individual exercises where the arm was the starting motor and always walking on tiptoe. We made up walks, runs, jumps and skips, backwards and forwards, with stops to maintain our balance and never resting on our heels. We all worked together in the same room, but by ourselves, isolated from each other. On one of the three days of the workshop, Torgeir asked us to make an improvisation about an important event in our lives. He explained that the improvisation should be done in silence, letting our actions be inspired by episodes from our biographies. As a point of departure I thought of my grandfather, of how, when I was twelve years old, he had forbidden me ever to cut my hair. It was the first association that came to my mind and it allowed me to use my hair as a tangible object. It was the first time that I improvised alone, without props, masks or puppets.

We also did some acrobatic exercises with Torgeir, during which I cut my chin. I had to be stitched up in hospital. The exercises resulted in my calf muscles hurting so much that I could only walk upstairs backwards. This is how I arrived to see Come! And the Day Will Be Ours (1976–80), the first Odin Teatret performance I experienced as a spectator. I did not understand it. Later I found out that the performance was about the meeting between European immigrants and the indigenous people of the Americas.

Meanwhile I organised the barter. I took Torgeir to Avanguardia Operaia’s centre in search of audience seating to use in the deconsecrated church of San Carpoforo, where Odin Teatret would present part of their performance The Book of Dances (1974–9). In the church I witnessed the cornice crumbling beneath Iben Nagel Rasmussen’s feet, as she got ready to descend from it. She was hanging on a long rope, dressed in her white costume and using a drum covered in colourful ribbons. I saw Tage Larsen dance with his big orange and purple flag, Tom Fjordfalk jump as he twirled a long stick while Roberta Carreri accompanied him playing drums. Else Marie Laukvik had been excused from taking part in the performance. We had arrived with our puppets and masks. The church was packed; many spectators remained outside, including my mother. I watched the performance from afar, but I recognised something familiar in the colours and dances of Odin Teatret. I felt affinity with this tribe, although I could not have explained why.

I cannot say that there was a first day in my apprenticeship as an actress, rather a long period characterised by all the experiences I have mentioned. Of the second period of apprenticeship, I remember an immense solitude. I had gone to visit Odin Teatret in Denmark with the idea of learning as much as I could in three months, in order to return to share my knowledge with my comrades in Milan. During the period in Holstebro I sought to understand stage presence by repeating handstands and back exercises against the wall whilst, day by day, my identity as a responsible, secure, socially active and politically involved person grew weaker. I could not speak the language and, anyway, they did not talk much in the North; I was not involved in any public performance or activity; I was not of use to anyone and I was confronted every day with my professional ignorance.

Three months were enough for me to feel the ground disappear from beneath my feet. I knew only one thing: I could not return to Milan and continue to be responsible for hundreds of young people with only the support of enthusiasm and words. I had chosen theatre as a way of saying ‘no’, of being ...