eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Written Composition

This is a test

- 389 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Written Composition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 1987. Part of a series on the psychology of education and instruction, this volume marks a highpoint in the development on writing from a cognitive perspective. It significantly expands the data base upon which our understanding of writing rests. the book presents an original theory, or at any rate, the beginnings of a theory of writing and the development of writing skills, emphasizing the control processes in writing.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Written Composition by Carl Bereiter, Marlene Scardamalia, Carl Bereiter, Marlene Scardamalia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Central Concepts

Chapter 1

Two Models of Composing Processes

1 Chomsky (1980) has argued that if we want to advance our understanding of the mind as a biological entity, we should study what it does easily and well. In particular, we should study those abilities that people acquire most naturally, with the least dependence on the environment. If that is to be the role of cognitive psychology, what becomes of instructional psychology? For if instructional psychology has a province, it is the province of things that have proved difficult to learn, that are believed to require substantial and purposely arranged contributions from the environment.

We would suggest that there are, in fact, complementary roles for a psychology of the easy and a psychology of the difficult, and that a complete cognitive science needs to encompass both. Research on cognition in infants and young children makes it increasingly evident that human beings come into the world already primed for certain kinds of knowledge. That is, they either already possess the knowledge in embryonic form or possess some kind of innate readiness to acquire it. Such appears to be the case not only with grammar, which is Chomsky’s prime example, but also number (Gelman & Gallistel, 1978) and perceptual organization (Spelke, 1982). On the other hand, human beings are distinguished by their ability to acquire expertise—that is, to develop high levels of ability and knowledge of kinds that do not arise naturally out of everyday living but that require sustained effort over long periods of time. Hayes (1981) has concluded that in all those areas where top levels of expertise are equated with genius, it takes 10 years of sustained effort to achieve the necessary knowledge and skill.

In the preceding paragraph we conflated easy with natural and difficult with requiring special provisions for learning. Obviously there is no strict correlation between the naturalness and the difficulty dimensions. Walking comes naturally, yet infants work hard at it. One must be taught how to drive a car, but it is not difficult for most people to learn. The key distinction, for which we have found no convenient labels, is between those kinds of abilities that are almost inevitably acquired through ordinary living (including ordinary living in school classrooms) and those that require some special effort to transcend naturally occurring limitations. With due recognition that the terms do not fully condense the intended meanings, we shall refer to the two kinds of abilities as natural and problematic.

A complete cognitive science needs to account for both ends of the natural-to-problematic continuum. But more than that, it needs to consider possible interactions, such as the following:

To what extent are the more problematic kinds of human capabilities built up from more naturally acquired capabilities?

To what extent may naturally acquired abilities stand in the way of development of more expert ways of performing the same functions?

In this book we want to consider written composition from the standpoint of naturally acquired and more problematic human capabilities, with a view toward issues like the two just raised. By looking at both the easy and the hard aspects and their interaction, we hope to contribute to understanding both the mind’s natural capabilities and what is involved in going beyond those natural capabilities.

WRITING AS BOTH NATURAL AND PROBLEMATIC

Writing—by which we mean the composing of texts intended to be read by people not present—is a promising domain within which to study the relationship between easy and difficult cognitive functions. On the one hand, writing is a skill traditionally viewed as difficult to acquire, and one that is developed to immensely higher levels in some people than in others. Thus it is a suitable domain for the study of expertise. On the other hand, it is based on linguistic capabilities that are shared by all normal members of the species. People with only the rudiments of literacy can, if sufficiently motivated, redirect their oral language abilities into producing a written text. Indeed, children lacking even the most rudimentary alphabetism can nevertheless produce written characters that have some linguistic efficacy (Vygotsky, 1978).

There is, indeed, an interesting bifurcation in the literature between treatments of writing as a difficult task, mastered only with great effort, and treatments of it as a natural consequence of language development, needing only a healthy environment in which to flourish. Convincing facts are provided to support both views. On the one hand we have evidences of poor writing abilities, even among relatively favored university students (Lyons, 1976) and professional people (Odell, 1980). On the other hand we have numerous reports of children taking readily to literary creation when they have yet scarcely learned to handle a pencil (Graves, 1983). While children’s writing is unquestionably recognizable as coming from children, it often shows the kind of expressiveness and flair that we associate with literary talent.

One could perhaps dismiss such contradictory findings as due to the application of different standards of quality. It may, in short, be easy to write poorly and difficult to write well. But that is a half truth which obscures virtually everything that is interesting about writing competence.

The view of writing that emerges from our research is more complex than either the “it’s hard” or the “it’s easy” view or any compromise that might be struck between them. We propose that there are two basically different models of composing that people may follow. It is possible to write well or poorly following either model. One model makes writing a fairly natural task. The task has its difficulties, but the model handles these in ways that make maximum use of already existing cognitive structures and that minimize the extent of novel problems that must be solved. The other model makes writing a task that keeps growing in complexity to match the expanding competence of the writer. Thus, as skill increases, old difficulties tend to be replaced by new ones of a higher order. Why would anyone choose the more complex model? Well, in the first place it seems that not very many people do, and it is probabably never used to the exclusion of the simpler model. But for those who do use it, the more difficult model provides both the promise of higher levels of literary quality and, which is perhaps more important for most people, the opportunity to gain vastly greater cognitive benefits from the process of writing itself.

One way of writing appears to be explainable within a “psychology of the natural.” It makes maximum use of natural human endowments of language competence and of skills learned through ordinary social experience, but it is also limited by them. This way of writing we shall call knowledge telling. The other way of writing seems to require a “psychology of the problematic” for its explanation. It involves going beyond normal linguistic endowments in order to enable the individual to accomplish alone what is normally accomplished only through social interaction—namely, the reprocessing of knowledge. Accordingly, we shall call this model of writing knowledge transforming.

A two-model description may fit many other domains in addition to writing. Everyday thinking, which is easy and natural, seems to follow a different model from formal reasoning, which is more problematic (Bartlett, 1958). Similar contrasts may be drawn between casual reading and critical reading, between talking and oratory, between the singing people do when they light-heartedly burst into song and the intensely concentrated effort of the vocal artist.

In each case the contrast is between a naturally acquired ability, common to almost everyone, and a more studied ability involving skills that not everyone acquires. The more studied ability is not a matter of doing the same thing but doing it better. There are good talkers and bad orators, and most of us would prefer listening to the former. And there are surely people whose formal reasoning is a less reliable guide to wise action than some other people’s everyday thought. What distinguishes the more studied abilities is that they involve deliberate, strategic control over parts of the process that are unattended to in the more naturally developed ability. That is why different models are required to describe these processes.

Such deliberate control of normally unmonitored activity exacts a price in mental effort and it opens up possibilities of error, but it also opens up possibilities of expertise that go far beyond what people are able to do with their naturally acquired abilities. In the case of writing, this means going beyond the ordinary ability to put one’s thoughts and knowledge into writing. It means, among other things, being able to shape a piece of writing to achieve intended effects and to reorganize one’s knowledge in the process. The main focus of this book is on the development of these and other higher-level controls over the process of composition.

FROM CONVERSATION TO KNOWLEDGE TELLING TO KNOWLEDGE TRANSFORMING

Although children are often already proficient users of oral language at the time they begin schooling, it is usually some years before they can produce language in writing with anything like the proficiency they have in speech. Longitudinal studies by Loban (1976) suggest that the catch-up point typically comes around the age of twelve. The most immediate obstacle, of course, is the written code itself. But that is far from being the only obstacle. Others of a less obvious nature are discussed in Chapter 3. These less obvious problems have to do with generating the content of discourse rather than with generating written language. Generating content is seldom a problem in oral discourse because of the numerous kinds of support provided by conversational partners. Without this conversational support, children encounter problems in thinking of what to say, in staying on topic, in producing an intelligible whole, and in making choices appropriate to an audience not immediately present.

In order to solve the problems of generating content without inputs from conversational partners, beginning writers must discover alternative sources of cues for retrieving content from memory. Once discourse has started, text already produced can provide cues for retrieval of related content. But they are not enough to ensure coherent discourse, except perhaps of the stream-of-consciousness variety. Two other sources of cues are the topic, often conveyed by an assignment, and the discourse schema. The latter consists of knowledge of a selected literary form (such as narrative or argument), which specifies the kinds of elements to be included in the discourse and something about their arrangement. Cues from these two additional sources should tend to elicit content that sticks to a topic and that meets the requirements of a discourse type. In essence, the knowledge-telling model is a model of how discourse production can go on, using only these sources of cues for content retrieval—topic, discourse schema, and text already produced.

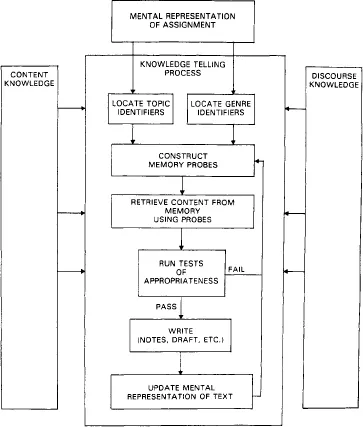

The main features of the knowledge-telling model are diagrammed in Figure 1.1. The diagram indicates a composing process that begins with a writing assignment. It could also begin with a self-chosen writing project, however, so long as there is some mental representation of the task that can be analyzed into identifiers of topic and genre or discourse type. The task might, for instance, be to write an essay on whether boys and girls should play on the same sports teams. Depending on the sophistication of the writer, the topic identifiers extracted from this assignment might be boys, girls, and sports or amateur sports and sexual equality. According to the model, these topic identifiers serve as cues that automatically prime associated concepts through a process of spreading activation (Anderson, 1983). This process does not ensure that the information retrieved will be relevant, but there is a built-in tendency toward topical relevance. As Anderson explains, “spreading activation identifies and favors the processing of information most related to the immediate context (or sources of activation)” (Anderson, 1983, p. 86). Naturally, the appropriateness of the information retrieved will depend on the cues extracted and on the availability of information in memory. For instance, one would expect that the cues, amateur sports and sexual equality, would have a greater likelihood of eliciting information fitting the intent of the assignment than would the cues, boys, girls, and sports, provided the writer had knowledge stored in memory related to those cues. In either case, however, the retrieval is assumed to take place automatically through the spread of activation, without the writer’s having to monitor or plan for coherence.

Figure 1.1. Structure of the knowledge-telling model.

Cues related to discourse type are assumed to function in much the same way. The assignment to write an essay on whether boys and girls should play on the same sports teams is likely to suggest that what is called for is an argument or opinion essay. Again, the cues actually extracted will depend on the sophistication of the writer. Some immature writers may have an opinion-essay schema that contains only two elements—statement of belief and reason (see Chapter 4). Others may have more complex schemas that provide for multiple reasons, anticipation of counterarguments, and so on. In any case, it is assumed that these discourse elements function as cues for retrieval of content from memory, operating in combination with topical cues to increase the likelihood that what is retrieved will not only be relevant to the topic but also appropriate to the structure of the composition. Thus, the cues, boys, girls, sports, and statement of belief would be very likely to produce retrieval of the idea that boys and girls should or should not play on the same sports teams, an appropriate idea on which to base the opening sentence of the essay.

According to the model shown in Figure 1.1, an item of content, once retrieved, is subjected to tests of appropriateness. These could be minimal tests of whether the item “sounds right” in relation to the assignment and to text already produced or they could be more involved tests of interest, persuasive power, appropriateness to the literary genre, and so on. If the item passes the tests it is entered into notes or text and a next cycle of content generation begins. Suppose, for instance, that the first sentence produced in our example is “I think boys and girls should be allowed to play on the same sports teams, but not for hockey or football.” The next cycle of content generation might make use of the same topical cues as before, plus the new cues, hockey and football, and the discourse schema cue might be changed to reason. A likely result, therefore, would be retrieval of a reason why boys and girls should not play hockey or football together. Content generation and writing would proceed in this way until the composition was completed.

This way of generating text content was described for us by a 12-year-old student as follows:

I have a whole bunch of ideas and write down until my supply of ideas is exhausted. Then I might try to think of more ideas up to the point when you can’t get any more ideas that are worth putting down on paper and then I would end it.

Knowledge telling provides a natural and efficient solution to the problems immature writers face in generating text content without external support. The solution is efficient enough that, given any reasonable specification of topic and genre, the writer can get started in a matter of seconds and speedily produce an essay that will be on topic and that will conform to the type of text called for. The solution is natural because it makes use of readily available knowledge—thus it is favorable to report of personal experience—and it relies on already existing discourse-production skills in making use of external cues and cues generated from language production itself. It preserves the straight-ahead form of oral language production and requires no significantly greater amount of planning or goal-setting than does ordinary conversation. Hence it should be little wonder if such an approach to writing were to be common among elementary school students and to be retained on into university and career.

KNOWL...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I Central Concepts

- Part II Basic Cognitive Factors in Composition

- Part III Perspectives on the Composing Strategies of Immature Writers

- Part IV Promoting the Development of Mature Composing Strategies

- Part V Conclusion

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index