The place of evidence-based practice in recent healthcare reforms

This book explores how clinicians 1 acquire and use their knowledge. They know they are expected to ensure that they adhere to the latest, preferably research-based, evidence about best practice, yet they do not always make the best use of the new sources of evidence such as clinical guidelines and systematic reviews of clinical trials (Haynes 1993; Lomas 1997; Evans and Haines 2000; Armstrong 2002; Haines et al. 2004; Wyer and Silva 2009). That conundrum is set against a background of health professions that are in a state of flux (Peckham and Exworthy 2003; Klein 2001; Harrison and McDonald 2008). Even by the 1990s the reputedly omniscient senior physician, the dependably avuncular general practitioner, the handmaiden nurse and the acquiescent patient were already disappearing. Across the health professions, where the traditional hierarchies were tumbling, new relationships between professionals were emerging (see, for example, Ashburner and Birch 1999; Childs 2008) with general practitioners employing increasingly larger numbers of nurse practitioners and indeed in some rare instances doctors and nurse practitioners combining on an equal footing to form general practices. Since then multidisciplinary teams have been increasingly expected to break down the old pecking order; innovative roles such as nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants have been blurring professional boundaries. Patients – gradually becoming relabelled as ‘clients’ by some health professions to stress this very point – seem often to know a great deal about, and are ever more encouraged to have a strong say in, how their illnesses are managed. To that end they now have potential access to rich resources of knowledge and advice not only through patients’ organizations but through the internet. Clinicians too are faced with many more sources of knowledge that they need to take account of when practising.

As a result the professions have been described as being ‘under siege’ (Fish and Coles 1998: 3). As clinical freedom and authority give way to managerialism, the once autonomous doctor must now comply with bureaucratic norms and targets or face the consequences (e.g. Ferlie et al. 1996). The clinicians’ employers might well constrain how they may or may not manage their patients. The shift of doctors’ status from self-determining professional to regulated employee has even been described as the ‘proletarianization’ of medicine (e.g. Elston 1991), a term that certainly reflects the shift of power but underplays the equally important shift in education, lifelong learning and the status of clinical knowledge.

The training of clinicians has evolved hand in hand with these changes in their environment. The tradition of undergoing a fixed period of didactic clinical teaching followed by bedside apprenticeship is being phased out across the healthcare disciplines in favour of more flexible, self-directed and reflective learning. New educational principles have been transforming clinical education through problem-based learning, inter-professional learning, competencies-based training, ever more rigorously objective examinations, continuous professional development, clinical audit, appraisal and revalidation. Lifelong learning has replaced the once-and-for-all qualification. There is increasing stress on delivering and checking competencies rather than inculcating values and professional wisdom (Fish and Coles 2005). The job for life is being supplanted by mobile career paths, portfolio careers and complex private/public partnerships that undermine the traditional job security of the health professional. Moreover, the specialized knowledge that clinicians bring to their practice no longer carries the arcane mystique that it once did. The incontestability of a senior clinician’s individual, autonomous knowledge has been undermined by the clinical guideline, the systematic review, the organizational target and the web-based expert system open to all, including patients. Senior doctors can be challenged by (perhaps brave) members of the clinical team who have read the latest guidance, or by patients who have had access to alternative sources of information about their disease, or by healthcare managers whose paymasters charge them with cajoling if not coercing clinicians to comply with new, more cost-effective ways of practising. As a result, the old acceptance that ‘we do things this way because distinguished professors tell us we should and it’s not for the likes of us to question it’ is much harder to sustain. In short, the clinical knowledge base is being democratized.

And this is just as well, since the old elitism had produced unacceptable variations in practice, dependent more on the power of opinionated senior doctors than on any rational review of all the appropriate evidence. Indeed it was that very problem that provided much of the fuel for both the democratization of clinical knowledge and the proletarianization of the clinical professions in the first place. The aim of many of the reforms was precisely to expose and minimize the clinical misjudgements of a lofty elite; to replace eminence-based practice with evidence-based practice.

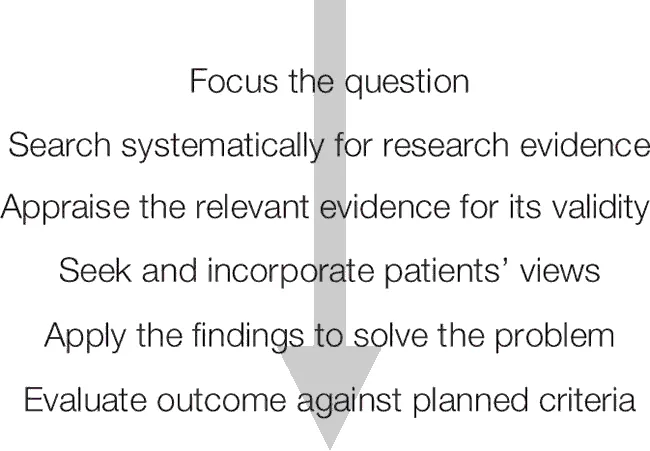

Evidence-based practice (EBP) took root in the medical profession in the 1990s (Sackett et al. 1997; Gray 1997) paralleled by other healthcare professions (Mulhall and le May 2004) and like all social movements it has had many forms and interpretations among friends and detractors alike (Harrison 1998; Timmermans and Berg 2003; Dopson et al. 2003; Pope 2003; Rycroft-Malone 2006). At its core, however, the EBP movement, in whatever guise it might appear, has urged clinicians to use the available research evidence either by finding, appraising and applying the best evidence themselves or through using evidence-based guidelines and treatment protocols (Figure 1.1).

When David Sackett and his colleagues, who spearheaded the movement, defined evidence-based medicine as ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al. 1996: 71; Straus and Sackett 1998; Haynes 2002), they were being more sophisticated than many who joined them to create the EBP bandwagon (Trinder and Reynolds 2000). 2 Sackett and colleagues’ definition recognizes the importance of clinical judgement when applying the best evidence in any given set of circumstances. In contrast, however, much of the organizational change linked to the EBP movement seems to have been about applying research evidence overzealously and unthinkingly in clinically inappropriate ways. Clinicians find themselves urged, for example, to apply the results of clinical trials that might have been carried out in selected minorities of patients who are quite different from the majority that they themselves treat. Or, worse, they find themselves under pressure to use clinical guidelines that are not always as explicit as they should be about the sources and the limitations of the evidence on which they are based (e.g. Grol et al. 1998; Lugtenberg et al. 2009).

EBP has led to a host of reforms across healthcare. They include the mass of guidelines now available to clinicians, many of which are now prepared to the very highest standards of evidence and practical relevance, even though – much to the dismay of those who carefully prepare the guidelines – clinicians are notorious for ignoring or rejecting them unless they are somehow coaxed or coerced into using them. EBP has also grown in tandem with the Cochrane Collaboration in which colleagues from around the world sign up to a lifelong mission to systematically review all the available research evidence using meticulously controlled and scrupulous techniques in order to inform best practice in their chosen area. 3 This has been revolutionary not only in the way it has critically collated huge quantities of research information that was previously ignored, misinterpreted or used inappropriately, but also in the way it has inspired an almost evangelical fervour to pursue high-quality evidence and discard bad science (CRAP writing group 2002). Excellent as it is, however, the Cochrane Collaboration still relies heavily on the randomized controlled trial as the chief arbiter of truth, playing down other forms of legitimate knowledge and still largely ignoring the social and economic aspects of healthcare. Moreover, on close examination the detail often seems to favour scientific pedantry over the needs of clinical practice. EBP has also fostered a welcome emphasis on applied health sciences (as characterized, for example, by the rise of pragmatic and complex trials, of health services research and of health technology assessment). A parallel development has been the growing industry of research on the implementation of research, little of which, paradoxically, is widely implemented. 4 Finally, we see the growing influence of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) not only in its native UK, but in countries the world over that are also experiencing pressures to deliver more cost-effective care. NICE issues both general guidelines and specific directives about new treatments; both are rooted in detailed and rigorous assessments of the evidence on cost-effectiveness. But, like many of NICE’s counterparts that are springing up around the world, its work is also accompanied by unprecedented levels of bureaucratization and organizational accountability in healthcare, designed to encourage if not enforce conformity to ‘best practice’.

Such changes have given reformers the opportunity to try to alter clinicians’ behaviour by using change management techniques to introduce more evidence into practice. In the UK, for example, the government has encouraged the ‘modernization’ of health services not only by injecting more cash into the NHS, but also by relentlessly changing the contractual relationship with health service providers in ways that are designed to encourage evidence-based practice and hence reduce variation in practice. A wide range of schemes have been aimed at the individual practitioner, from training and education programmes to revalidation of their competence to practise, in order to try and corral clinicians and ensure conformity to current best evidence (e.g. Mulhall and le May 1999; Grimshaw et al. 2001, 2004). Such activity has been complemented by measures designed to improve the available knowledge base; these include new resources for applied research and new tools (e.g. the development of care pathways) to foster compliance, and national service frameworks (NSFs) that set out best practice, evidence based as far as possible. Whether that has succeeded in improving standards of care – which it almost certainly has done, if patchily – or has been as distressing and disruptive to practice as some complain, is not the point here. The fact is that such measures are transforming the professional basis of healthcare.

The result of this sea change is that practitioners are nowadays more likely to be exposed to the best evidence either directly or – more usually – through widely promulgated guidance. And few would now dispute the principle that clinical practice should be based on the best available evidence, or that the basic principle of EBP is potentially beneficial to practice and hence to patient outcomes. (What can be wrong with systematically and explicitly reviewing and using all the available evidence about the likely effects of alternative courses of action before making a clinical decision? Moreover, can increasingly cash-strapped health systems afford the waste that occurs when clinicians act idiosyncratically?) But there have been many barriers to overcome, not least the defiance of clinicians, and especially those who argue that the evidence is often impracticable, irrelevant or absent, and takes too long to find (Grol 1997; Newman et al. 1998; Dopson and Fitzgerald 2005). Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs have all played their part in that resistance (le May et al. 1998; Ferlie et al. 2001; Dopson et al. 2010 [2002]), as have the complexities of organizational behaviour (Ferlie et al. 2000). The knowledge base both of individual clinicians and of the relevant sciences in general has often been inadequate to sustain EBP; the attitude of clinicians has often been one of wariness of the motives and competence of those producing guidance or advocating changes to practice; and strongly held beliefs have undermined the use of evidence. In one study of the implementation of EBP, for example (Dawson et al. 1998), the senior hospital doctors believed that the guidelines on asthma and glue ear did not apply to their specialized and complicated patients, while the general practitioners believed that the guidelines did not apply to their mostly atypical patients, and the junior doctors said they really didn’t have time to practise evidence-based medicine (EBM) and anyway had to do as their bosses told them. In short – at least in the 1990s when EBM was relatively new – all parties believed that the guidelines applied to someone else but not to them. Catch-22. Yet the direction of central policy is tending inexorably towards more protocol-driven systems of care, exacerbating the potential tensions between clinical autonomy and rationalist bureaucracy (Gray and Harrison 2004).

Even where there has been a willingness to adopt evidence and try to change practice, organizational barriers such as inadequate resources or inappropriate systems have provided further obstacles. For example, one might accept the importance of scanning all patients who have had strokes, but what if the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners are not available (CSAG 1998)? Perhaps above all, practitioners have found that the science base is often not there when they need it; that there are still large shadows of uncertainty where the evidence is too insubstantial to justify a change in practice. That, indeed, is why there has been such an increase in needs-led, service-oriented research whose aim is to produce answers to the practical questions facing clinicians (Baker and Kirk 2001). Yet, despite that increase, the landscape still seems full of grey areas and unresolved questions (Chalmers 2008; James Lind Alliance 2010). In sum, for all these reasons and more, while there has been a reform in the way evidence is applied to practice, the change is not nearly as radical or fundamental as the proponents of EBP might wish.