Chapter 1

Assessing the Cultural Validity of Assessment Practices An Introduction

Guillermo Solano-Flores

Defining Cultural Validity

As with any other product of human activity, tests are cultural artifacts. They are a part of a complex set of culturally established instructional and accountability practices; they are created with the intent to meet certain social needs or to comply with the mandates and legislation established in a society; they are written in the language (and the dialect of that language) used by those who develop them; their content is a reflection of the skills, competencies, forms of knowledge, and communication styles valued by a society—or the influential groups of that society; and they assume among test-takers full familiarity with the contexts used to frame problems, the ways in which questions are worded, and the expected ways to answer those questions.

Viewing tests as cultural artifacts (see Cole, 1999) enables us to appreciate that, to a great extent, the ways in which students interpret test items and respond to them are mediated by cultural factors that do not have to do necessarily with the knowledge assessed. This is a matter of validity—scores obtained by students on a test should not be due to factors other than those that the test is intended to measure (Messick, 1995). This is as true of classroom assessments as it is of large-scale assessments.

While key normative documents on testing (e.g., AERA, NCME, & APA, 1999; Hambleton, 2005) recognize the importance of factors related to culture and language as a source of measurement error, current testing practices address culture as a threat to validity rather than the essence of validity. Culture is part of the discourse on test validity but is not viewed as the essence of a form of validity in its own right.

In 2001, we (Solano-Flores & Nelson-Barber, 2001, p. 555) proposed the concept of cultural validity, which can be defined as:

the effectiveness with which [. . .] assessment addresses the socio-cultural influences that shape student thinking and the ways in which students make sense of [. . .] items and respond to them. These socio-cultural influences include the sets of values, beliefs, experiences, communication patterns, teaching and learning styles, and epistemologies inherent in the students’ cultural backgrounds, and the socioeconomic conditions prevailing in their cultural groups.

Along with this definition, we contended that the cultural factors that shape the process of thinking in test-taking are so complex that culture should not be treated as a factor to correct or control for, but as a phenomenon intrinsic to tests and testing. We argued that both test developers and test users should examine cultural validity with the same level of rigor and attention they use when they examine other forms of validity.

The notion of cultural validity in assessment is consistent with the concept of multicultural validity (Kirkhart, 1995) in the context of program evaluation, which recognizes that cultural factors shape the sensitivity of evaluation instruments and the validity of the conclusions on program effectiveness. It is also consistent with a large body of literature that emphasizes the importance of examining instruction and assessment from a cultural perspective (e.g., Ladson- Billings, 1995; Miller & Stigler, 1987; Roseberry, Warren, & Conant, 1992). Thus, although cultural validity is discussed in this chapter primarily in terms of large-scale assessment, it is applicable to classroom assessment as well. This fact will become more evident as the reader proceeds through the book.

In spite of its conceptual clarity, translating the notion of cultural validity into fair assessment practices is a formidable endeavor whose success is limited by two major challenges. The first challenge stems from the fact that the concept of culture is complex and lends itself to multiple interpretations—each person has their own conception of culture yet the term is used as though the concept were understood by everybody the same way.

As a result of this complexity, it is difficult to point at the specific actions that should be taken to properly address culture. For example, the notion of “cultural responsiveness” or “cultural sensitivity” is often invoked by advocates as critical to attaining fairness (e.g., Gay, 2000; Hood, Hopson, & Frierson, 2005; Tillman, 2002). However, available definitions of cultural sensitivity cannot be readily operationalized into observable characteristics of tests or their process of development.

The second challenge has to do with implementation. Test developers take different sorts of actions intended to address different aspects of cultural and linguistic diversity. Indeed, in these days, it is virtually impossible to imagine a test that has not gone through some kind of internal or external scrutiny intended to address potential cultural or linguistic bias at some point of its development. Yet it is extremely difficult to determine when some of those actions are effective and when they simply address superficial aspects of culture and language or underestimate their complexities. For example, the inclusion of a cultural sensitivity review stage performed by individuals from different ethnic backgrounds is part of current standard practice in the process of test development. While necessary, this strategy may be far from sufficient to properly address cultural issues. There is evidence that teachers of color are more aware than white, mainstream teachers of the potential challenges that test items may pose to students of color; however, in the absence of appropriate training, teachers of color are not any better than white teachers in their effectiveness in identifying and addressing specific challenges posed by test items regarding culture and language (Nguyen- Le, 2010; Solano-Flores & Gustafson, in press).

These challenges underscore the need for approaches that allow critical examination of assessment practices from a cultural perspective. While assessment systems and test developers may be genuinely convinced that they take the actions needed to properly address linguistic and cultural diversity, certain principles derived from the notion of cultural validity should allow educators and decision-makers to identify limitations in practices regarding culture and language and ways in which these practices can be improved.

This chapter intends to provide educators, decision-makers, school districts, and state departments of education with reasonings that should enable them to answer the question, “What should I look for in tests or testing programs to know if appropriate actions have been taken to address culture?” These reason-ings are organized according to four aspects of cultural validity: theoretical foundations, population sampling, item views, and test review.

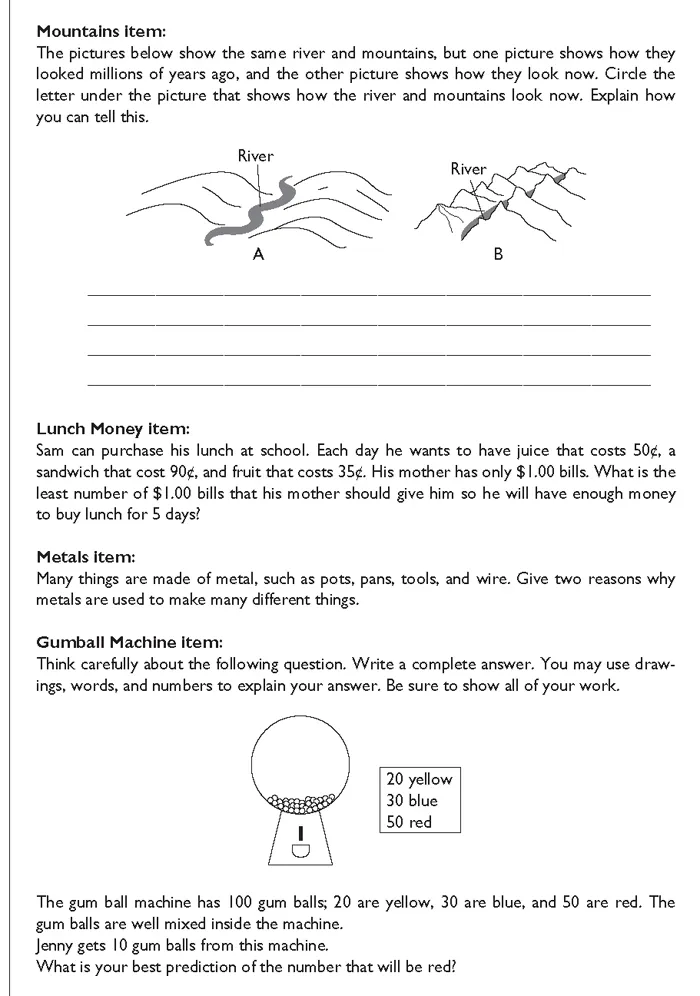

In discussing these aspects, I share lessons learned and provide examples from three projects funded by the National Science Foundation (for a discussion of the methodological aspects of these projects, see Solano-Flores & Li, 2006, 2008, 2009; Solano-Flores & Trumbull, 2008). The first project, “Assessing the Cultural Validity of Science and Mathematics Assessments,” investigated cultural influences on test-taking. Grade 4 students from 13 cultural groups (each defined by a unique combination of such factors as ethnicity, geographical region, ancestry, socioeconomic status, and linguistic influences) verbalized their thinking as they responded to the NAEP items shown in Figure 1.1 (see National Assessment of Educational Progress, 1996) and responded to interview questions on the ways in which they interpreted them.

The second project, “Cognitive, Sociolinguistic, and Psychometric Perspectives in Science and Mathematics Assessment for English Language Learners,” examined how scores obtained by English language learners vary when they are tested in English or in their native language or in the local or standard dialects of those languages. The third project, “Teacher-Adapted Versus Linguistically Simplified Items in the Testing of English Language Learners” investigated the advantages of using language adaptations made by teachers on tests as a form of testing accommodation for English language learners (ELLs) tested in English. These two projects addressed language from a sociolinguistic perspective that takes into consideration the social aspect of language and the fact that language use varies across social groups. More specifically, these projects examined the extent to which the scores of ELL students in tests vary due to language and dialect variation (Solano-Flores, 2006). As a part of the activities for these two projects, we worked with teachers from different linguistic communities with the purpose of adapting tests so that their linguistic features reflected the characteristics of the language used by their students.

For discussion purposes, throughout this chapter, language is regarded as part of culture. However, when appropriate, language or linguistic groups are referred to separately when the topics discussed target language as a specific aspect of culture. Also, the terms “assessment” and “test” are used interchangeably.

Figure 1.1 Items used in the project (source: National Assessment of Educational Progress, 1996. Mathematics Items Public Release. Washington, DC: Author).

Theoretical Foundations

Testing practices should be supported by theories that address cognition, language, and culture. Regarding cognition, testing practices should address the fact that cognition is not an event that takes place in isolation within each person; rather, it is a phenomenon that takes place through social interaction. There is awareness that culture influences test-taking (Basterra, Chapter 4, this volume). Indeed, every educator has stories to tell on how wording or the contextual information provided by tests misleads some students in their interpretations of items. However, not much research has been done to examine the ways in which culture influences thinking during test-taking.

There is a well-established tradition of research on the cognitive validation of tests that examines students’ cognitive activity elicited by items (Baxter, Elder, & Glaser, 1996; Hamilton, Nussbaum, & Snow, 1997; Megone, Cai, Silver, & Wang, 1994; Norris, 1990; Ruiz-Primo, Shavelson, Li, & Schultz, 2001), as inferred from their verbalizations during talk-aloud protocols in which they report their thinking while they are engaged in responding to items, or after they have responded to them (Ericsson & Simon, 1993). Surprisingly, with very few exceptions (e.g., Winter, Kopriva, Chen, & Emick, 2006), this research does not examine in detail the connection between thinking and culture or has been conducted mainly with mainstream, white, native English speaking students (see Pellegrino, Chudowski, & Glaser, 2001).

Regarding culture and language, testing practices should be in accord with current thinking from the culture and language sciences. Unfortunately, many actions taken with the intent to serve culturally and linguistically diverse populations in large-scale testing are insufficient or inappropriate. For example, many of the accommodations used by states to test ELLs do not have any theoretical defensibility, are inappropriate for ELLs because they are borrowed from the field of special education, or are unlikely to be properly implemented in large-scale testing contexts (Abedi, Hofstetter, & Lord, 2004; Rivera & Collum, 2006; Solano-Flores, 2008).

In attempting to develop approaches for ELL testing that are consistent with knowledge from the field of sociolinguistics, we (Solano-Flores & Li, 2006, 2008, 2009) have tested students with the same set of items in both English and their first language and in two dialects (standard and local) of the same language. Dialects are varieties of the same language that are distinguishable from each other by features of pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary, among others (see Crystal, 1997; Wolfram, Adger, & Christian, 1999). Rather than testing these students with bilingual formats, the intent is to determine the extent to which ELL students’ performance varies across languages or dialects. Generalizability theory (Brennan, 1992; Cronbach, Gleser, Nanda, & Rajaratnam, 1972; Shavelson & Webb, 1991, 2009)—a psychometric theory of measurement error—allows examination of language as a source of measurement error and, more specifically, the extent to which student performance varies across languages or dialects.

An important finding from our studies is that, contrary to what simple common sense would lead us to believe, ELLs do not necessarily perform better if they are tested in their native languages. Rather, their performance tends to be unstable across languages and across items. Depending on the item, some students perform better in English than in their native language, and some other students perform better in their native language than in English. Our explanation of this finding is that each item poses a unique set of linguistic challenges in each language and, at the same time, each ELL has a unique set of strengths and weaknesses in each language.

Another important finding from those studies speaks to the complexity of language. If, instead of being tested across languages, students are tested across dialects of the same language (say, the variety of Spanish used in their own community and the standard Spanish used by a professional test-translation company), it can be observed that their performance across dialects is as unstable as their performance across languages.

These findings underscore the fact that no simple solution exists if we are serious about developing valid and fair assessment for linguistic minorities (Solano-Flores & Trumbull, 2008). Testing ELLs only in English cannot render valid measures of achievement due to the considerable effect of language proficiency as a construct-irrelevant factor. The same can be said about testing ELLs in their native language. Valid, fair testing for ELLs appears to be possible only if language variation due to dialect is taken into consideration.

Our f...