CHAPTER 1

Mobility and the interchange

Mobility in developed countries accounts for around 60–100 minutes per day of a person’s time irrespective of the mode of travel employed (walking, cycling, bus, metro, train). In spite of travel restrictions such as car-free zones, the distances travelled increase year by year. To a degree also, the time spent on travel increases annually but, as public transport becomes more efficient and interchanges more effective, the travel distance available within a set period of time expands. Hence suburbs and new towns are built ever further away from traditional urban centres. However, if public transport can take people further within a specified timeframe, this is not true of private transport, which suffers from two inefficiencies – congestion and regulation. The balance of power has switched in most of the world (though not the USA) from private modes of travel to public ones. The car is seen as increasingly un-environmental and also antisocial, and hence access for the car in urban areas in gradually being restricted. So in spite of greater affluence and more flexible lifestyles, the shift from private cars to public buses, trains and trams is a characteristic of the early years of the twenty-first century.

However, the change in travel mode is not universal, neither is it consistent across cultures and age groups. The age group of 25–35 is particularly wedded to the car. Here it is a question of lifestyle choice, of convenience – particularly for parents whose children need to attend school in low-density suburbs, and of image. The wealthy can afford to drive, the poor cannot. Even when there are incentives to use buses, such as free bus travel and prioritised bus lanes through congested streets, many in this age group choose the security and one-upmanship of the car to what is perceived to be less safe and socially acceptable trains and buses. Although car restraint is essential in order to change habits, the image of public transport and its connectors (stations, bus stops etc.) is a major obstacle to social change. So, although we need legislation, travel is a cultural statement as well as a functional necessity. We are how we travel or, put another way, we assert our sense of worth by the means of transport we adopt. So to ride a bike to work is to make a cultural statement; to choose to walk rather than drive is to send a message to your neighbours. Conversely, to use a large four-wheel drive vehicle in the suburbs shows a disregard for both the social and physical environment.

Many people carry prejudices about the quality of public transport, such as the ‘trains are always late’ or the ‘metro is dangerous at night’ or ‘stations are filthy’ or ‘bus stations are full

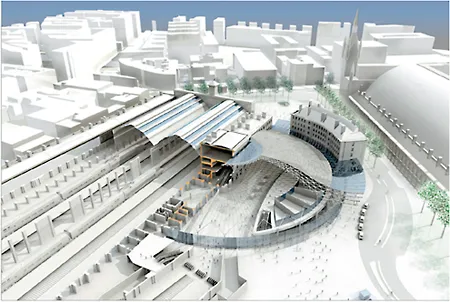

of homeless people’ (Freudendal-Pedersen, 2009). One role of design is to combat these poor images by projecting an optimistic, more utopian vision for public transportation. It is also important that existing problems with stations and interchanges are addressed, such as graffiti, poor lighting, vandalised seats, inadequate travel information and much else. Upgrading image is primarily a question of upgrading management practices and refreshing design. Also it is worth noting that those who complain most about public transport are those who don’t use it, and those who make policy decisions tend to drive rather than take the bus or train. As a result, there is a gap in vision between those who take public transport as a matter of course and those who rarely do and who legislate on our behalf. The latter rarely wait around for trains, ferries or buses in dark stations or on windswept piers and streets.

Mobility does not have to be based on cars and on fossil fuels. Electrical energy produced from wind, solar and nuclear installations powers high-speed trains across Europe, and diesel used for many of the buses in Latin America and Asia comes from biofuels. Walking and cycling depend solely on human muscle energy produced by metabolism with only limited fossil fuel consequences. Hence, the totality of the mobility debate touches upon questions of energy use, access, equality and health. Put another way, urban transportation is as much about sustainable development as it is about the popular debate surrounding the greening of cities and low-energy architectural design. The major means of getting around are walking, cycling, car, taxi, bus, tram, train and aircraft. In reality we use some or all these modes often in conjunction with a single journey from home to work. Combining modes of travel raises the question of interconnection – of moving

smoothly and efficiently from one type of transport to another. Here, the transport interchange comes into its own. The interchange recognises the interdependency of modern urban life – the plurality and complexity that underpin the contemporary situation. However, functional separation of land uses and their supporting transport modes, which was the mantra of modernism, has left a great deal of inefficiency and redundancy in our cities.

New transport modes, hybrid technologies and the future

One characteristic of transport buildings is that they are always having to adapt to innovations in the mode of transportation. This is not new. Steam that powered trains was replaced by diesel and then by electric traction motors, with single-deck carriages replaced by double-decker layouts; buses became hybrid fuel driven and extended into train-like configurations with concertina carriage joins; ferry boats became fast hover and then hydrofoil craft; trams adopted elements of bus and train technologies to run on city streets without pollution or excessive speed. The latest trams run on rubber tyres and use dedicated bus lanes, thereby blending the genes of rail and buses to create cost-effective mass urban transportation. In Curitiba, Brazil, such vehicles carry two million passengers a day, making the kind of expensive and disruptive tram infrastructure provision found in Edinburgh redundant. The story is one of stations, ferry terminals, airports and interchanges adapting to survive under relentless technological innovation.

Generally, technological change in the transport industry is driven by three forces: the need to improve efficiency, especially

in energy consumption and people moving capacity; the need to exploit new markets in mass people movement; and the need to improve customer comfort levels. In Darwinian terms, it is not the most intelligent or strongest infrastructure that has survived, but those elements of public transportation that have proved most flexible and willing to change. Hence the interchange has emerged in response to new social and economic dynamics, departing in the process from the thoroughbred form of the traditional railway station or airport. The modern interchange is a hybrid that accommodates new transportation technologies and seeks to provide expression for the interconnected nature of modern multicultural and pluralistic life. The ability to handle large numbers of transferring passengers, to process complex movement patterns while also producing buildings of quality, comfort and architectural distinction, is the challenge ahead.

Looking forward there are several innovations on the horizon that may alter the pattern of transport use and hence the interchange. The first concerns the development by the Canadian company Bombardier of trains powered by lightweight jet engines. Designed for long-distance journeys, the jet-powered train offers better speed and acceleration without the cost of overhead electric power lines (Schilperoord, 2006: 120–7). The jet train, particularly if energy efficiency can be improved and biofuels exploited, may threaten the high-speed dominance of the French TGV, German ICE and Japanese Shinkansen technologies. Potentially too it could challenge air transport for mid-distance travel, particularly in the USA and Canada, where train infrastructure is under developed and buses have withdrawn from the mid-haul market. Magnetic levitation technology (MagLev) also offers potential since weight is reduced and power efficiency increased perhaps tenfold over wheeled transportation. MagLev also overcomes the problem of noise, which is one of the major restraints on high-speed trains, especially in urban or suburban areas. Innovation here is centred in China with Shanghai being the first planned

practical application (ibid.). Other innovations include monorail urban transit systems (which are already functioning well in Vancouver and Las Vegas), fuel cell bus technologies and hybrid bus–light rail formats. These dual road/rail vehicles run on both metal tracks and rubber tyres, creating flexibility at the urban–suburban–rural interfaces. A similar hybrid, although at less cost, is the triple articulated diesel bus, which runs in Curitaba in Brazil. Powered by bio-diesel, these have dedicated lanes and fully enclosed bus stops with automatic barriers akin to those employed on tram systems. These bus/tram hybids are less expensive than rail systems but employ similar technologies and offer higher levels of passenger comfort than traditional buses.

In terms of aircraft there is research and development in the area of double-decker planes, dual jet–glider configurations and hybrid plane–train technologies utilising high-speed train traction for aircraft. One characteristic of all these developments is that they offer greater energy efficiency and improve the operational performance of public transport. Necessarily, the stations, terminals and airports that serve the infra structure of mobility ne...