![]()

I

MASS MEDIA AND GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS

![]()

Introduction to Political Communication

• The Health Insurance Association of America was worried. President Bill Clinton had introduced a sweeping plan to reform health care, and the Association, a lobbying group for 270 insurance firms, was nervous that Clinton's health reform package would put insurance companies out of business.

To fight the Clinton plan, the lobbying group did what lobbying groups do in the 1990s when they want to defeat a legislative package: It hired pollsters, political consultants, and advertising professionals in an effort to influence public opinion.

The Health Insurance Association blitzed the television airwaves in the summer and fall of 1993, spending tens of millions of dollars on advertising and polling. One of its commercials, “Harry and Louise,” became a campaign classic. It featured a man called Harry and a woman named Louise complaining about how government bureaucrats were forcing them to pick from a few health care plans. “Having choices we don't like is no choice at all,” lamented Louise. “They choose,” said Harry. “We lose,” replied Louise.

Although the Harry and Louise ads grossly oversimplified and distorted Clinton's plan, they captured the national spotlight. First Lady Hillary Clinton attacked them. So, too, did influential Democrats. And, to the delight of the insurance industry, the more the Clinton administration criticized the spots, the more publicity they received. It was a public relations executive's dream.

A year later, after months of attack ads, news stories covering the campaign for and against Clinton's proposal, vitriolic commentaries on talk radio, and bureaucratic bungling by the Clinton administration, the health care reform plan was dead. And as the pundits asked what went wrong, 37 million Americans remained without health insurance, and health care costs continued to skyrocket.1

• Every day, from dawn to dusk, radio talk-show hosts scream and shout, and lambast and lacerate American politics and politicians. For example:

In Los Angeles, talk-show host Emiliano Limon of KFI asks, “If homeless people cannot survive on their own, why shouldn't they be put to sleep?”

In Colorado Springs, Chuck Baker of KVOR says of the attorney general, “We ought to slap Janet Reno across her face … (and) send her back to Florida where she can live with her relatives, the gators.”

In New York, the I-man, Don Imus, called Newt Gingrich “a man who would eat road kill,” O. J. Simpson “a moron,” Alice Rivlin a “little dwarf,” Bob Novak the man with “the worst hair on the planet,” and Ted Kennedy “a fat slob with a head the size of a dumpster.”2

Imus and other talk-show hosts can be funny, irreverent, and cruel. They also attract huge audiences. Talk is now the most popular radio format after country music, commanding 15% percent of the radio market. Talk radio has sparked considerable controversy: Critics say it taints and tarnishes the nation's conversation about politics; defenders say it provides millions of Americans with a venue to express their anger and frustration with the system.

Whatever its merits, there is no doubt that people and politicians are listening. When he ran for president in 1992, Bill Clinton realized that he could reach millions of New York voters by appearing on Imus's radio program. So even as Imus mocked Clinton, calling him a “redneck bozo,” Clinton appeared on his show, trading insults with Imus, and at the same time reaching the gargantuan New York radio audience. Clinton went on to win the New York primary by a huge margin.

Later when Clinton became president, Imus received a VIP tour of the White House and lunched with Clinton's communications director. But the Lman wasn't fazed by the royal treatment. The president, he claimed, “needs to be on this show a lot more than we need him.”3

• Concerned by evidence that the public has lost confidence in the news media, dozens of news organizations have recently begun to experiment with new strategies to get the public involved in political issues.

Known as public journalism, the new movement steers clear of traditional reporting of conflict and official intrigue; instead, editors roll up their shirt sleeves and get involved in community problems, as participants rather than observers.

For example, in the fall of 1994, four Madison news media joined forces to get citizens involved in the state election campaign. The newspaper, public radio station, and two local TV stations organized town hall meetings in three Wisconsin cities to stimulate discussion of the gubernatorial race. A candidate debate, with questions from audience members, followed. The debate was simulcast live on public radio and public TV stations. Research showed that the Madison project increased knowledge of public affairs and drew people into he electoral process.4

The Charbtte Observer in North Carolina called on public journalism concepts in its news coverage of a much different situation—a racial conflict that had developed over the use of a city park. African-American young people had been using the park's lot as a gathering place for car cruising. This angered White residents of the neighborhood, and when city officials agreed to ban cruising from the park, the situation grew tense.

Rather than just cover the conflict, The Observer tried to find solutions to the problem. Reporters conducted lengthy interviews with the teenagers, asking them if they thought there should be more activities for young people and what would happen if the city tried to find a new spot for their cruising.

“Our reporting turned from just reporting conflict to interviewing a lot of people about what should happen, what is the solution here,” explained Rick Thames, the newspaper's assistant managing editor. “The dialogue began to take place inside our newspaper that wasn't taking place in any other forum.” The newspaper converge helped to defuse the crisis.5

From health care reform to talk radio to public journalism, the mass media are at the vortex of modern political communication. Unlike previous eras, when much of the business of politics was conducted in private back-room sessions, nowadays political campaigns are conducted in the public sector, with the mass media a major weapon in the battle for public opinion.

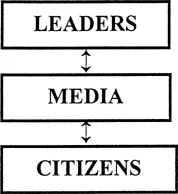

This book focuses on political communication and the complex interplay of influence among policymakers, the media, and the public. It traces the evolution of modern political communication, looking at changes and continuities in political media over the course of this country's history. It explores theories of political media, the impact of media in elections, and ways to improve the nation's dialogue about political issues.

As we will see, communication has always played a role in politics in the United States. It is part of the dynamic experiment in self-government that America's Founding Fathers launched over 200 years ago. The democratic ideal—the notion that people can govern themselves, elect leaders, and run a society by the rules of representative democracy—has captured the imagination of leaders and citizens in America from the beginning of the nation's history to the present day.

It is a complex system, this American system of politics and political communication, a system fraught with puzzles and paradoxes. We are a nation in which a man (Ross Perot) can rise from a middle-class background to make billions in a computer business dedicated to handling Medicare claims, then rail against the government that made him his fortune, launch a presidential campaign on a television talk show, inspire thousands of volunteers to support his candidacy, spend millions of his personal fortune on television advertising, and in 1992 capture 19% of the popular vote, an achievement that a less affluent candidate carrying the same message could never possibly have attained.

America is a nation that has more media—from newspapers to radio to television to the Internet—than any nation on earth, more coverage of the political campaign appearing in more media outlets than any other nation, a panoply of analyses, commentaries, and book-length syntheses of politics, politicians, and electoral campaigns. Yet we are a nation in which most people blithely choose to ignore the information that they can obtain from these many sources and instead opt to get most of their news from television, which even its most celebrated news anchors acknowledge is at best a headline service, never meant to be the sole source of political information for citizens in a democracy.6

America is a nation that celebrates democracy every Fourth of July, but increasingly finds that elections, the centerpiece of democracy, are terribly expensive affairs, costing in the hundreds of millions; they are events in which interest groups and parties trip over one another to figure out ways to use campaign finance loopholes to raise more money for electoral campaigns. The American presidential election attracts the interest of millions of Americans when conventions and presidential debates roll around, stimulates citizens to learn more about their candidates, yet nonetheless fails to rouse millions of other—more disenchanted—citizens out of their lethargy and apathy. Typically, no more than 55% of the public votes in presidential elections.

Yet for all the paradoxes and failures to live up to the ideals set forth by the Founding Fathers, the nation's political communication system has shown resilience and openness to change, from the introduction of the primary system in the early 1900s to the advent of public journalism in the early 1990s.

The manner and style in which politics is communicated in this country—a complex and controversial subject—is the focus of this book. The discussion takes us from the administration of George Washington to that of Bill Clinton, from presidential press conferences to local boosterism. The book examines the many ways in which messages are constructed and communicated from public officials through the mass media to people like you and me.

DEFINING THE TERMS

When it comes to politics, many Americans would agree with Finley Peter Dunne's fictional character, Mr. Dooley, that “politics is still th' same ol' spoort iv highway robb'ry.” Study after study shows that Americans hold their elected officials in low esteem and have less confidence in government to do the right thing than they did a generation ago.7 To many Americans, politics conjures up negative images—laundered money, shady deals, corruption in high places.

Of course, some of this exists. Talk to people in Chicago and they will regale you with stories —some steeped in myth, others based in fact—of how convicted felons have held high political office in the city of broad shoulders. As I discuss later in this book, there is reason to be concerned about ethical violations and abuses in contemporary politics. Nonetheless, there is much that is good in politics—it is politics, after all, that brought about the United States of America, and that has produced major changes including the 19th amendment that gave women the right to vote, civil rights legislation, and Social Security.

Yet for a variety of reasons, people harbor negative attitudes toward politics. There are many reasons for this, including the news media's tendency to emphasize conflict rather than efforts to build consensus, politicians' own tendency to exploit the media to showcase their opponents' vulnerabilities, and the public's predilection for simple explanations of a complex political scene. Thus when conflicts develop over legislative matters and the parties are at loggerheads, people frequently shake their heads, and say, “It's just politics.” But as Samuel Popkin notes, “That's the saddest phrase in America, as if ‘just politics’ means that there was no stake.”8

What is politics? Simply put, it is “the science of how who gets what and why.”9 More complexly, it is “a process whereby a group of people, whose opinions or interests are initially divergent, reach collective decisions which are generally regarded as binding on the group, and enforced as common policy.”10

This book focuses not just on politics, but on the communication of political issues, on what an academic journal calls “press-politics” and what scholars call political communication.11 One of the theses of this book is that you cannot understand the current political scene without appreciating the role and impact of mass media. This is hardly a controversial thesis. With the decline of political parties and the rapid diffusion of television, the mass media have come to perform many of the functions previously reserved for