Part 1

Analysing contexts

In order to respond positively to learner diversity, teachers have to understand how children and young people experience what is on offer within the school. This also requires that they identify and address barriers that may be making it difficult for some students to participate and learn.

The chapters in this first part illustrate how evidence of various forms can be used to analyse school and classroom contexts in order to identify such barriers and determine resources that can be used to address these difficulties. These examples focus on a range of contexts and stages of education.

A feature of all the accounts is the way the authors explore innovative ways of understanding the experiences of learners. So, for example, in addition to well-established research methods, such as questionnaires, observation and interviews, the authors explore the use of drawings, photographs, games, learning walks, video recording and mind mapping.

In Chapter 1, Annita Eliadou describes how children’s drawings can shed more light on social interaction within schools than would have been possible using more traditional methods of educational research. Building on the experience of conducting a collaborative school-based inquiry in England, she used sociometric techniques in Cyprus to represent children’s social interactions diagrammatically and to analyse friendship patterns in relation to their ethnic backgrounds.

Chapter 2 provides a detailed contextual analysis of an extremely diverse inner city primary school responding positively to the effects of poverty, migration and poor health, while engaging with the government’s school improvement requirements and its own internal change agenda following the appointment of a new head teacher. The research methods Michele Moore used to carry out her investigations – observations and interviews – are familiar. However, as a researcher in the school who also worked for the local authority, her inquiry required her to address various dilemmas.

Then, in Chapter 3, Debra Martin describes research she carried out to gather the views of teenagers in a pupil referral unit about their experiences in secondary schools. The methods she used to break down possible barriers between young people and adults were particularly interesting in that they allowed her to capture their views on a very sensitive topic.

In Chapter 4 we read Clare Millington’s account of her detailed investigation of the efforts of a rural primary school to include one child who uses a communication aid. Finally, Chapter 5 moves to a very different context in considering how Harriet Rowley and Sarah Butson dealt with the challenges of encouraging a pupil-voice approach to research and development in a special school for refugees in India.

Chapter 1

Using children’s drawings to explore barriers to inclusion in Cyprus

Annita Eliadou

In this chapter, I explain how children’s drawings can be used to investigate the topic of social interactions within schools catering for highly diverse student populations and the presence of friendship patterns as these develop in relation to children’s ethnic backgrounds. While studying for a Master’s degree at the University of Manchester, I had the opportunity to participate, along with three other colleagues, in a school-based inquiry project carried out in a school which catered for a multi-ethnic student population (Eliadou et al. 2007a). As was discovered while doing research at this school, the school staff collaborated in taking great measures to ascertain that all students at the school were included in all aspects of their everyday school experiences. Attention was paid to: ensuring the presence of all students at school on a daily basis; giving students opportunities for participation both during in-class activities and extracurricular activities; motivating them to achieve well academically; and encouraging a climate in which all students were socially included at school.

This was a school where students were made aware of each other’s national identities, the difference in languages spoken and the different cultures and customs existent in the school. Nonetheless, the school principal showed an interest in investigating in greater depth the topic of social inclusion. His concern lay with the fact that students from the same ethnic background seemed to socialize independently of students from other ethnic backgrounds during break time. This piece of school-based inquiry was therefore preoccupied with identifying whether the social inclusion of students was compromised in any way due to the multi-ethnic character of the school, and, in case this was true, in exploring what the reasons giving rise to such findings might be. Hence, this project demanded the identification and use of a research method that would enable the investigation of students’ social interaction at school. The method adopted was a drawing technique followed by procedures of sociometric analysis, which allowed the diagrammatical representation of students’ social interactions at school. This research method identified that students from specific ethnic backgrounds were socializing in segregated groups. The findings suggested that even a school, which at first glance seemed to be very inclusive, still had a lot to struggle for in order to offer its students a more inclusive educational experience (Eliadou et al. 2007b).

Following this project, and for the purpose of my Master’s dissertation, my attention turned to the educational experiences offered to students within the educational system of Cyprus (my country of origin), which had only recently attempted to implement principles of inclusive education (Koutrouba et al. 2006). Moreover, this educational system had to face the challenge of having to respond to the increased student diversity (ethnic, linguistic, religious) arising from the increased immigration rates recorded in Cyprus over the previous two decades (MOEC 2005; MOEC 2008). I wondered, therefore, whether it would be appropriate to use the same research method, used in a school in England, to investigate social inclusion in a school in Cyprus? If schools in England, dedicated to promoting principles of inclusive education were still struggling to promote inclusion amongst their students, what would I find in Cyprus?

The use of drawings as a research tool

The use of drawings within the research design employed for my Master’s dissertation was aimed primarily at presenting a research tool to explore social interactions within a school with a multi-ethnic character, which, in addition, promoted “student voice.” It has been evident that in recent years there has been a growing emphasis on involving students in the research process, since children are considered to be both worthy of investigation and as having the right for their “voice” to be heard (Einarsdottir et al. 2009). Researchers preoccupied with using research in ways that enhance “student voice” have attempted to identify innovative research methods that provide the researcher with the potential to carry out research with children, rather than on children (Mitchell 2006; Thomson 2008).

Since researchers within the realm of social sciences have been searching for innovative methods that align with the conceptualization of children as social agents and cultural producers (Mitchell 2006), there has been a renewed interest in research involving children’s drawings. In addition, recent research has moved away from the psychological stance of describing children’s drawings in terms of developmental sequences, and toward considering children’s expressions of meaning and understanding (Einarsdottir et al. 2009). Nonetheless, there have been relatively few published studies that have used drawings as an innovative, alternative way to understand children’s knowledge and experience; and even fewer where children are invited to be co-interpreters (or narrators) of their own images (Leitch 2008).

When researchers have used drawings within their research, they have been provided with an invaluable tool for the elicitation of children’s perspectives on their life experiences, especially when children are encouraged to discuss their drawings (Einarsdottir et al. 2009; Leitch 2008; Mitchell 2006; Thomson 2008). Incorporating drawings in research has been useful since drawing is an activity that children engage with in their everyday lives (Einarsdottir et al. 2009) and thus they find pleasure in it (Einarsdottir et al. 2009; Leitch 2008; Mitchell 2006; Thomson 2008); it does not require the use of complex technology (Mitchell 2006); and is particularly effective to use with children that have difficulties with verbally expressing themselves (Eliadou 2007; Eliadou et al. 2007b; Thomson 2008).

This latter characteristic proved to be highly constructive in this study, since it meant that the drawing technique would not offer a “communicative disadvantage” to the participants (Mitchell 2006). Most of the student participants in this study had been recent arrivals to the case study schools and had not yet acquired basic linguistic skills in the Greek language, which is the official language used in the educational context of Cyprus. Thus, using an image-based research technique proved to impose less linguistic demands on the participants and was therefore more enjoyable to participate in. Moreover, relying on the production of visual rather than text data minimized the strain placed on the researcher when trying to interpret and analyze the data collected, since children offered interpretations of their own drawings.

An example of exploring children’s social interactions through the use of drawings

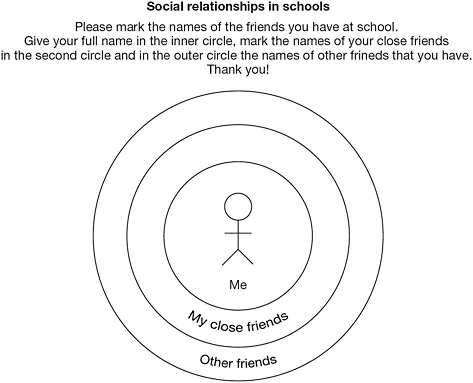

While conducting research in Cyprus, one primary school and one secondary school served as case studies and, therefore, as examples of schools that catered for highly diverse student populations. In each of the case study schools the student participants were given a drawing task and were asked to record the names of “close friends” and the names of “other friends,” using a pre-planned drawing task arrangement. Different drawing arrangements were presented to primary school students and secondary school students to make the task more age appropriate. At each school each participant had 15 minutes to complete their drawing. The drawing task was presented to 60 students at the secondary school and required that students recorded the names of five “close friends” and the names of five “other friends” (Figure 1.1).

The drawing task presented to students at the primary school was less complicated and required that 40 students drew themselves and their friends and that they recorded the names of the friends presented in the drawing (Figure 1.2).

All drawings were collected at the end of the task and analyzed in an attempt to explore the nature of the social relationships formed at the specific schools in terms of how responsive students were to the increased student diversity. Students were subsequently asked to comment on their drawings and their social interactions at school in a focus group discussion that took place after data from the drawing task was analyzed. I have not retained any of the original drawings that the children produced since one of the conditions of participation at the schools was that all drawings that included personal information would be destroyed for ethical reasons at the end of