![]()

I

FOUNDATIONS FOR PERSONNEL DECISIONS

The four chapters in this first part of the book describe the context within which assessment-based personnel decisions are made. Chapter 1 introduces varieties of personnel decisions but identifies staffing decisions as a prototype for other kinds of personnel decisions; staffing decisions include, among others, selection, transfer, assignment to special training, promotion, or termination decisions. When done best, the decisions are based not on intuition or habit, but on assessments of performance, other contributions to organizational goals, or predictions of such things. We emphasize the ideal of data-based decisions. Chapter 2 describes procedures for analysis of jobs and organizational needs to follow in setting goals to be achieved through assessment and prediction. Chapter 3 describes hypothesis formation in thinking through the ways those goals might be achieved by specifying the variables (i.e., constructs) to be predicted or to be used as predictors. The notion of testing predictive hypotheses is central to the book as a whole and is often returned to. Finally, Chapter 4 presents the legal context for personnel decisions in the United States—and recognizes but offers no details on similar contexts elsewhere—the requirements and constraints that govern what organizations can and cannot do in making assessment-based decisions about people.

![]()

1

Membership Decisions in Organizations

Organizations consist of members. Their members; the tools, equipment, and supplies available to them; their goals and purposes; their research activity; the community services they offer; their influence beyond the organization—such things create environments, social and physical and ideational, for their members and also for customers or vendors. Members are important; “workers should be viewed as long-term assets, not short-term costs” (Gowing, Kraft, & Quick, 1998, p. 261).

Organizations change. They grow or decay; they merge with others or divest themselves of functions and find new ones. Members die, retire, or change jobs and may (or may not) be replaced, and member roles change as organizations do. Organizations also face and react to external change. Some buggy-makers, facing the future, started making automobiles. In the automotive industry, skilled craftsmen made cars; product quality depended on their individual skills. Then mechanical equipment made assembly lines possible, and relatively unskilled workers could do what craftsmen had done—and with precision permitting interchangeable parts. Now much of automotive assembly is automated, and robots do things people used to do; fewer workers are needed, and many who are left are highly trained in new electronic crafts. Member roles and required qualifications changed as work environments changed from social to mechanical to electronic.

Change occurs spasmodically and in pockets—like “scattered showers” in a weather forecast. At any given moment, some people, and the organizations within which they work, do things in a totally new way; others stick to tradition. Sticking to tradition is partly perseveration (perhaps resistance to change), but it also happens because the stimulus for change doesn’t occur everywhere at once. Besides, to recall collegiate French, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose—the more things change, the more they stay the same. Despite Frank Landy’s urging that I follow his trend to find every job in this book and replace it with work, I find daily use still bemoans the loss of jobs in times of recession/depression, meaning work that gets paid. And, like Ilgen and Pulakos (1999), I believe that employee performance remains paramount to the health of both the employing organization and its members.

Not everyone joins an organization. People in some occupations—professionals, people in trades or crafts, farmers, or consultants among them—may form their own small organizations or work independently. Some of them must be certified individually to the public, to customers, or perhaps to potential employers that they are competent in what they do. Nevertheless, nearly everyone in a modern society works in some form of organization.

Organizations function through their members. Recruiting and hiring new members are chronologically the first steps in bringing in new people. Hiring new people is the end state of a selection process and is only one of several kinds of personnel decisions. The selection process—choosing among applicants those will be hired—is a prototype for the processes leading to many other kinds of decisions. I use selection as a generic term for deciding who among a field of candidates shall have a specific opportunity. Every hire (at whatever level), every promotion or transfer, every acceptance for special training, implies an agreement that employer and employee will work together for mutual benefit, often called a psychological contract, rarely formalized, often unrecognized until it is broken. The term acknowledges that the employer (employing organization) expects to gain something by offering the opportunity for a position in it. The selection process should make clear what the employer expects (e.g., through realistic job previews) and also what may be offered in return (related to pay, hours, working conditions, and more). In return, the person offers something (skills, special knowledge, dependably showing up and working well). The person also has expectations, such as a reasonable degree of permanence or opportunity for advancement.

New members (or old members in new roles) are chosen for fairly specific organizational roles—fairly specific sets of functions, duties, and organizational responsibilities—in the belief that choosing them will benefit the organization. “Fairly specific” is the right term. Some may be chosen to do very well-defined tasks, others to do whatever is needed in a loosely defined area. A role may be quite specific if the new member is simply taking the job of someone who has left. It is less specific if the newcomer offers relief to someone in an overloaded role or does things not assigned to anyone else—or if organizational policy is to give lots of latitude. Work roles may change over time, starting with specified activities but shedding or adding functions and purposes along the way.

Personnel decisions are based, if organizational leaders are not too whimsical and impulsive, on some sort of assessment of the person and prediction (explicit or implicit) of future behavior. It is always hoped that the decisions are wise. Consequences of wise decisions can range from the mere absence of problems to genuinely excellent outcomes promoting organizational purposes, such as substantial increases in mean performance levels and productivity. Consequences of unwise decisions can range from inconvenience to disaster.

The best personnel decisions are based on information permitting at least an implicit prediction that the person chosen will be satisfactory, perhaps better than others, in the anticipated role. The prediction is based on known or assumed attributes (traits) of the candidate.

ANTECEDENTS OF PERSONNEL DECISIONS

Once one or more applicants have been identified, selection decisions follow a typical chain of events: (a) identification of relevant traits, (b) assessment of candidates in terms of those traits, (c) prediction of probable performance or other outcomes of a decision to hire, and(d) the decision to hire or to reject (or, with more promising candidates than positions to fill, the decision to hire one in preference to others). The chain is often longer, but these seem generally minimal.

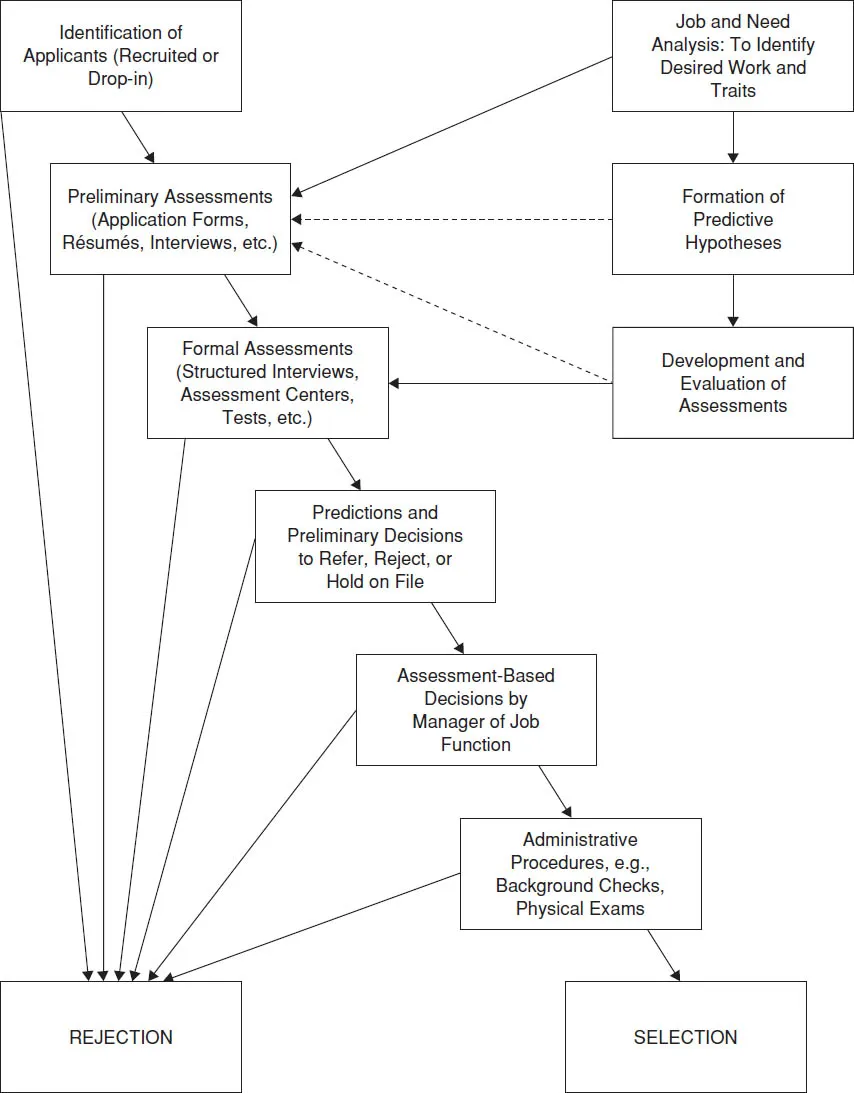

One illustrative employment process for choosing new members is shown in Figure 1.1. It has two chains. One of them, condensed to three big steps, is the support chain providing data and logic in support of the other. The actual decision chain is presented in more detail. The support chain, a personnel research chain, begins by gathering information about the work to be done in the job at hand, the needs and goals of the organization, and the development of ideas about what should be predicted and what traits are likely to predict it (predictive hypotheses), and the various processes conducted in seeking evaluative evidence to support the hypothesis chosen. The decision chain begins by identifying job candidates, those who have responded to recruiting efforts or have submitted applications. Sometimes a person may not be considered a candidate, even if applying, if not meeting certain basic qualifications such as being old enough to drive a vehicle legally or having required diplomas or other credentials. Each candidate’s relevant traits (those defined by predictive hypotheses) are assessed, informally or by formal, structured assessment procedures. From the assessments, predictions and decisions are made. The “selection” might be hiring a new employee, promoting one already on hand, deciding who will get special training or transfer, etc.

FIG. 1.1 Steps that may be followed in an organization’s selection procedure.

Recruiting

Recruiting is intended to attract people to an organization and its work opportunities; selection picks for employment the most qualified people among those who are attracted and become applicants. To recruit good applicants, organizations advertise openings, sometimes using classified ads or internet sites. They may place institutional ads in magazines or electronic media to enhance an organizational image. They may offer incentives to current employees to recruit friends. They send people to interview potential candidates, as in campus recruiting, and they do more image-enhancement in home-base interviews. Job previews, preferably realistic, are considered an integral part of the process. Recruiting is competitive, competing with other organizations “to identify, attract, and hire the most qualified people. Recruitment is a business, and it is big business” (Cascio, 2003, p. 201).

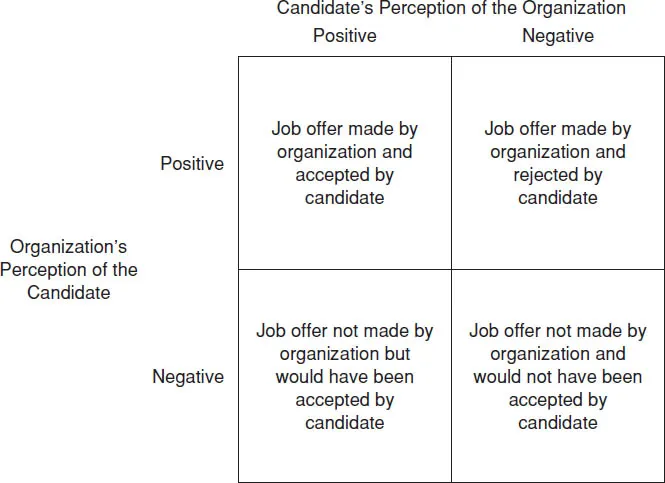

Recruitment is not a one-sided organizational activity. Candidates are not passive. New entrants into the labor market find the recruiting efforts of various employers and even make special efforts to be recruited (including pounding pavements). People who have been employed also seek jobs, whether because of losing jobs, intent to reenter the workforce after a hiatus, or desire to change jobs or to find a different career (Kanfer, Wanberg, & Kantrowitz, 2001). The job seeker must read ads, watch the TV bits, or check internet sites and form evaluative perceptions of advertised jobs and of advertising organizations. At the end of the process, as shown in Figure 1.2, the employer decides to offer employment (or not), and the candidate decides to take it (or not); that is, the candidate self-selects. “Self-selection occurs when individuals choose whether to apply for a job, to continue in a selection process or pursue other opportunities, or to accept or decline offers” (Ryan, Sacco, McFarland & Kriska, 2000, p. 163). Declining or opting out of the process at some point is known as “selecting-out.” If the employer makes an offer and the applicant accepts, their mutual expectations constitute an implicit psychological contract. When an organization offers a candidate a job, and when an applying candidate accepts the offer, both decisions seem to imply intent to stay together for a long time. ASA theory (Schneider, 1987; Schneider, Goldstein, & Smith, 1995) points out that this may not be the case. An applicant who is attracted to the organization and selected as a new member of it may find, in time, that the organization is no longer so attractive; perhaps the organization finds that new employee has not fulfilled the employee part of the implicit contract. In either case, attrition may result when the applicant leaves or is terminated.

FIG. 1.2 Candidate and organization perceptions: Outcomes of good and poor matching. From Catano, V. M., Cronshaw, S. F., Wiesner, W. H., Hackett, R. D., & Methot, L. L. (1997). Recruitment and selection in Canada. © 1997 Nelson Education Ltd. Reproduced by permission.

Applicant Reactions

Attraction to an organization or job depends partly on information and partly on perceptions of, and subjective inferences about, organizational characteristics (Lievens & Highhouse, 2003). On the basis of information, inferences, and perceptions, people decide for themselves whether they will be available to be selected. One important influence is a recruit’s expectation of justice; expectations are formed before things actually happen, and it behooves organizations to try to create positive expectations and to avoid unintentional influences that may be negative (Bell, Wiechmann, & Ryan, 2006).

Ryan et al. (2000) followed candidates for police work through a multiple-hurdle process; demographic diversity was a major objective of the process. Early drop-outs from the process were those with a more negative view of the organization and less commitment to police work than those who stayed through the process or dropped out later. Many of those passing the first hurdle also concluded that either staying in their current job or seeking another alternative was preferable. Self-selection may be useful to an organization, if as in this example it helps avoid hiring uncommitted people, but it can be undesirable if it means losing a highly qualified applicant to a competitor. That, of course, might be good for the person if the choice leads to more money, less commuting, a more congenial culture, or some other personally desirable outcome (Harris & Brannick, 1999).

Recruiting research, whether concerned about reactions of applicants or about performance of those hired, tends to be focused at the individual level, a factor in what Saks (2005, title) called “the impracticality of recruitment research” (emphasis in original). It is the research he deemed impractical, not recruiting per se. Personnel research methods have been largely limited to organizational actions and their consequences at the individual level; only recently have serious research designs begun to take account of the multiple layers of actions and results at and above the individual as multilevel research designs have been developed (see Klein & Kozlowski, 2000).

Recruiting is not a “personnel decision” about an individual applicant. It is not like other decisions grouped under the umbrella of selection, but it has an impact on such decisions. Recruiting cannot be separated from selection procedures; it is part of the selection procedure because it influences the applicant population and the usefulness of other aspects of the selection process (Schmitt & Chan, 1998). For example, if recruitment seeks innovative people, it is silly to assess recruits for ability to follow directions (Higgs, Papper, & Carr, 2000).

TABLE 1.1

Comparison of Selected External Recruitment Methods

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Newspaper Ads | Quick, flexible | Expensive |

| | Specific market | Short lifespan for ads |

| Periodicals/Journals | Targets specific groups ... |