![]() Part I

Part I![]()

Chapter 1

Movement at the Periphery

A Morphology of Pattern for Kinetic Facades

Architecture has typically resisted kinetics, yet there is a poetics of movement emerging at the periphery. This book examines the zone between environment and interior, the architectural facade, in search of a latent aesthetic enabled by kinetics. What precedent might inform theory and practice? What actually is being designed, when the outcome is in constant flux? These questions reveal the relative development of kinetic design within architecture. The design of motion is typically outside architecture’s domain, and while there are many engaging technology prototypes, there is minimal ‘content‘. By content I mean, for lack of a better phrase, kinetic composition. Composition is used here as a broad and open-ended term, allowing for directed and indeterminate approaches to the design of kinetics. The lack of content and the step outside the traditions of static form provide a challenge for this new field of design research, as there is no coherent body of theory to reference, nor are there sufficient designs to critique. This sparse landscape has led to the trajectory of this study, which undertakes a sectional slice through relevant theory, and uses this to inform the generation of ‘content’ in the abstract. The motivation is that of a designer, examining the lay of the land before traversing it. Through critique and experiment, the aim is to locate the contours of this new design space.

While there is an underlying poetic agenda, the inquiry has a succinct focus, which leads to a mode of design research bordering on the scientific. The approach is to examine the design of kinetics from the bottom up, to locate the various parameters that influence kinetic form, and through methodical indexing and intuitive experimentation, generate abstract studies of form in motion. This focus on the underlying structure of kinetics is accepted as being reductive, but a necessary first move that floats above the contingency of technology, site and brief. The ideas here are developed outside the world of matter, to provide an abstract point of reference for those interested in the poetry of movement.

The scope of the search for kinetic form is encapsulated in the phrase morphology of pattern for kinetic facades. Morphology is aligned with the manner in which Philip Steadman speaks of essential forms1 and its use by George Rickey in his Morphology of Movement.2 Kinetics is defined as spatial transformation, with a clear distinction being made in relation to several traditions of movement in architecture. Facade is positioned alongside other terminology such as envelope and skin, before distinguishing this research from kinetic structure and operable interiors. The fourth term, pattern, when considered in relation to kinetics for the particular context of a facade, is more difficult to define at the onset. This emerges, through critique of precedent in the kinetic arts and when developing design variables, which are argued to be the most influential in its formation. Multiple permutations of kinetic pattern, as evident through close examination of animation experiments, provide further insight. The distinctive qualities of kinetic pattern for architectural facades, and the compositional potential these afford, are central themes that shape the inquiry.

Morphology

Morphology is typically associated with the field of biology, and refers to the outward appearance and physical structure of an organism, as opposed to physiology, which primarily deals with functional processes.3 The term has been used in architecture in reference to urban morphology, and in design research on the geometry of plans. According to Batty, urban morphology developed around the establishment of the journal Environment and Planning B in 1973.4 From the onset urban morphology has concentrated on the underlying structure of urban form, primarily around the issue of accessibility. As proposed by Batty, the emphasis of contemporary research has shifted from the modelling of static structures to understanding the process by which they come about. The second strand of research within architecture which explicitly uses the term morphology is the analysis of building plans. As introduced by Philip Steadman in his book Architectural Morphology, the emphasis is on exploring the possible range of plan forms within geometric limits.

It is primarily concerned with the limits which geometry places on the possible forms and shapes which building and their plans may take. The use of the term ‘morphology’ alludes then to Goethe’s original notion, of a general science of possible forms, covering not just forms in nature, but forms in art, and especially the forms of architecture.5

Morphology for this design research is more aligned with Steadman’s exploration of possible forms than with urban morphology. Just as he explored the limits of planar configuration, this research will undertake a study of kinetic composition. However, while there is similar intent, caution needs to be exercised in making a direct comparison, particularly in relation to methodology. Inspired by the projective drawing techniques of D’Arcy Thompson, Steadman uses a mathematical approach to define rectilinear plan configurations. The possible range of plans is limited by ‘the underlying symmetry lattice or grid by which the pattern is organized’.6 Mathematics is also used to calculate room relationships using graph theory.7 Steadman explores morphology as a form of design science, literally calculating possible combinations of rooms within geometric limits. These techniques are not considered to be directly applicable to the orientation of this inquiry, which embraces a more liquid approach to morphogenesis. The emphasis here is on locating the underlying parameters that determine kinetics, and using these in an open-ended design experiment to produce a series of animation studies. Close scrutiny of the animations identifies consistent types of resonance that occur when manipulating design variables. This location of typical thickenings in the multiplicity of possible form, provides a slice through the new space of possibility afforded by kinetics.

While this research does not utilize Steadman’s mathematical analysis and is deliberately open ended rather then definitive in its aspirations, one technical aspect of his approach is adopted. In a careful introduction to his book, he makes the case for the dimensionless representation of plans.8 His argument is that configurations of possible types are best considered in terms of abstract geometric relationships, rather than the dimensions of the spaces. Nor is the physical thickness or materiality of walls considered. For Steadman, morphology is a study of geometric relationships independent of scale or materiality. In a similar manner, the dimensions of kinetic parts or the overall size of a facade are not crucial to the morphology of kinetic pattern. The focus of this study of morphology is on the configuration of geometric transformation in space, the underlying structure of kinetic formation, independent of physical scale or materiality.

A second relevant source for morphology is found in the kinetic arts. Towards the end of an essay titled The Morphology of Movement, artist and theorist George Rickey discusses the situation of kinetics as a new genre, in which there was a lack of significant forms, around which practice could reference and develop. Writing in 1963, Rickey articulates the need for an understanding of the range of forms for the new field of kinetic art. He argues that form ‘is without immediate aesthetic or quality implications’,9 and it is in this context that Rickey attempts to outline the essential forms of movement, or the term he uses for his essay, morphology. The question posed by Rickey for kinetic art can be repeated for the emerging practice of kinetic facades. What are the significant forms, independent of value appraisals or production context, and what is the theoretical range around which practice can reference and develop? Steadman shares a similar aspiration for the theoretical range of geometric plan types, independent of production context or value appraisal.

‘Morphology’ is the word which Goethe coined to signify a universal science of spatial form and structure. Goethe’s method in botany, where his first morphological interests lay, was intended not just to provide abstract representations, and a classification, of the variety of existing plants, but to extrapolate beyond these and to show how recombination of the basic elements of plant form could create theoretical species unknown to nature.10

It is with a similar intent that morphology underpins this research. Through abstract representations and the recombination of basic elements of kinetics, the aspiration is to locate the theoretical range of kinetic form, extrapolating beyond contemporary practice and historical precedent.

Kinetics

A clear distinction needs to be made between kinetics and other approaches to designing for movement and time. Typically, architectural theory and practice have engaged with movement in terms of:

- transformation through the event of occupation

- physical movement of the occupant

- a sense of movement due to the optical effects of changes in light or the presence of moisture

- the weathering of materials and effects of decay

- the representation of movement through form and surfaces that appear dynamic

- design methods that use geometric transformations or other animation techniques.

Each of these modes is outlined below, with the observation that many are inherent capacities of architecture, or constitute design approaches that have been exploited throughout history. The section concludes with a definition of kinetics, which focuses the scope of this research to areas outside these typical approaches to considering movement in architecture.

The first mode – change due to the event of occupation – is relatively self-evident, but has been articulated most clearly in Bernard Tschumi‘s thesis that architecture acts as a frame for ‘constructed situations’.11 For example, his 1989 Bibliothèque de France competition entry crossed sports and library programmes to alter the architectural experience. Here the building itself is typically inert, but with architectural ‘movement’ occurring due to indeterminate programmatic encounters. The building is transformed over time by the event of occupation, to create both literal movement in terms of occupancy and activity, but also movement in terms of the perception of the architecture – the stadium empty, for example, versus the stadium heaving with spectators. This capacity is inherent in all architecture but, as articulated by Tschumi, can be deliberately exploited to place architecture in a constant state of occupational flux.

The second tradition of movement is also inherent: architecture is experienced by the body in motion and through vision that is constantly shifting focus. The seminal essay, ‘A picturesque stroll around Clara-Clara’, traces a genealogy of the peripatetic view, from the Greek revival theories of Leroy, the multiple perspective of Piranesi, Boulee’s understanding of the effect of movement, to the Villa Savoye where architecture is best appreciated, according to Le Corbusier, ‘on the move’.12 This type of movement is reliant on the mobility of the surveyor in relation to typically inert form. The third mode occurs where perception of static surface, form and space is altered by changing environmental conditions. In this case, buildings can be designed to accentuate visual transformation in response to different light intensity and direction, the presence of moisture, and wind conditions.13

At a completely different order of time is the ageing of materials. Patina is typically resisted by contemporary forms of construction, but as explored in On Weathering, there is a long tradition of exploiting the properties of materials to design in deformation over time.14 A fifth mode of engagement with the theme of movement has its origins in the early twentieth century – the representation of motion through dynamic form. With links to Italian Futurism and German Expressionism, buildings such as Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower appear as if they are in motion, with streamlined profiles and smooth uninterrupted surfaces.15 A more recent digital engagement in relation to movement and time in architecture has developed around tactics of geometric transformation, as used in design process. As explored by Terzidis, this has origins in constructivism.16 He argues that the computer extends this agenda by facilitating the animation of geometry, such as the sweeping of sectional profiles along paths.17 While his study of kinetics utilizes similar tactics of geometric transformation to those explored here, there is a fundamental difference. For the design of static architecture, geometric transformation is a design method, with the ultimate goal of locating one frozen moment. For kinetic facades, there is no singular moment in time. The design outcome is shifting patterns of geometry in a constant state of flux.

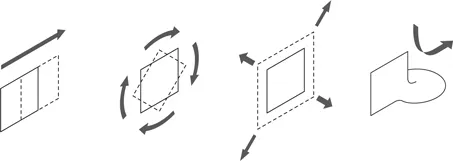

While acknowledging the ongoing relevance of the above approaches for architecture, the focus here is on the implications for design when kinetics is defined in spatial terms. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, this includes movement through three geometric transformations in space – translation, rotation, scaling – and movement via material deformation.

Figure 1.1 Definition of kinetics as three spatial transformations and material deformation

Translation describes movement of a component in a consistent planar direction; rotation allows movement of an object around any axis; while scaling describes expansion or ...