This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Policy and Law in Heritage Conservation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book has been developed in association with the Cultural Heritage Department of the Council of Europe. It examines key themes and objectives for the protection of the architectural and archaeological heritage in a range of European countries. The analysis of individual countries and the group as a whole gives an assessment of how advanced current mechanisms are and the ongoing problems that remain to be managed in order to safeguard the 'common heritage'.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Policy and Law in Heritage Conservation by Robert Pickard, Robert Pickard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

Context of the study

At the Second Summit of the Council of Europe, held in Strasbourg in October 1997, the Heads of State and Governments of the member states of the Council of Europe reaffirmed the importance attached to ‘the protection of our European cultural and natural heritage and to the promotion of awareness of this heritage’. An Action Plan adopted by the summit decided on the need to launch a campaign on the theme Europe, A Common Heritage to be held ‘respecting cultural diversity, based on existing or prospective partnerships between government, education and cultural institutions, and industry’ (Fig. 1.1).

This campaign, which was launched in September 1999 and intended to last for one year, takes place 25 years after the European Architectural Heritage Year (1975). The 1975 campaign marked the start of the Council of Europe’s activities that gave rise to the European Charter of the Architectural Heritage and subsequently the Amsterdam Declaration of the Congress on the European Architectural Heritage which introduced the concept of ‘integrated heritage conservation’. This concept is now enshrined in the founding texts, the Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (1985) (the Granada Convention) and the European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (revised) (1992) (the Malta Convention).

The contracting parties to the Granda Convention have undertaken to make statutory measures to protect the architectural heritage which would satisfy certain minimum conditions laid down in the convention. These included the maintenance of inventories, the adoption of integrated conservation policies and the setting up machinery for consultation and cooperation in various stages of the decision-making process (including with cultural associations and the public), the provision of financial support and the fostering of sponsorship and of non-profit making associations, and the promotion of training in the various occupations and craft trades involved in the conservation of the architectural heritage. In addition, the convention endorsed the need for European co-ordination of conservation policies including the exchange of experiences.

Fig. 1.1 Europe – A Common Heritage: a Council of Europe Campaign 1999–2000 (Campaign Logo).

The Malta Convention, replacing the earlier 1969 convention on the archaeological heritage, took note of the fact that the growth of major urban development projects made it necessary to find ways of protecting this heritage, including the provision of legal and financial machinery. The contracting parties to the 1992 revised convention have undertaken to devise supervision and protection measures and to promote an integrated policy, public awareness and co-operation between the parties and to facilitate the pooling of information.

It is within this context that this study has been developed in association with the Cultural Heritage Department of the Council of Europe. While the department’s Technical Cooperation and Consultancy Programme has developed a programme of legislative and administrative assistance through its Legislative Support Task Force to support countries in meeting the objectivies of the conventions, including the provision of Guidance on the Development of Legislation and Administration Systems in the Field of Cultural Heritage (Council of Europe, 2000), there has been little published evidence of the extent of implementation of the provisions contained in the Granada and Malta Conventions or of the commonality of legal and policy provisions adopted by different countries in Europe.

The aim of this study, therefore, is to examine some key themes and objectives for the protection of the immovable heritage within a representative sample of European countries. Since 1993 the Council of Europe has increasingly focused its attention on assisting new member states, particularly the countries of central and eastern Europe. In light of this, a sample of thirteen countries has been chosen from different the regions of Europe. The sample includes countries of the west that have already made significant progress in developing systems for the protection of the immovable heritage and a smaller group to illustrate the situation in countries currently in the process of reforming their legislation and institutions in this field.

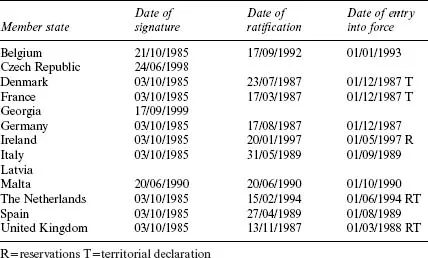

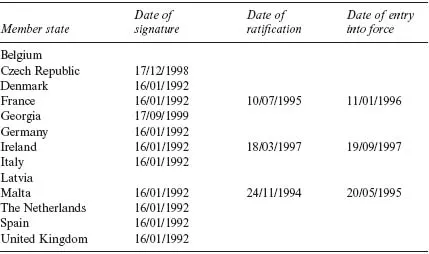

Undoubtedly, practice will vary between each country under consideration particularly as some of the countries are still in the process of developing laws and policies for the protection of the architectural and archaeological heritage. This can be reflected in Tables 1.1 and 1.2 which identify the countries and the position, as at the commencement of the year 2000, as to whether they have signed, ratified or brought into force the provisions of the Granada and Malta Conventions.

From Table 1.1 it can be seen that the representative sample of countries chosen for this study have largely signed, ratified and brought into force the provisions of the Granada Convention. It should be noted that Latvia and Georgia have been working to reform cultural heritage and associated legislation since 1996, with the assistance of the technical experts of the Legislative Support Task Force operated through the Cultural Heritage Department of the Council of Europe and the reform process for both countries is expected to be completed by 2001.

Table 1.1 The Granda Convention (European Treaty Series no. 121) – adoption of provisions by member states under study

Table 1.2 The Malta Convention (European Treaty Series no. 143) – adoption of provisions by member states under study

The situation regarding the Malta Convention is clearly not as advanced, as that of the Granada Convention due to the more recent date of the convention (Table 1.2). However, it should be emphasized that there has been progress on agreeing some common goals for the protection of archaeological heritage as indicated by the fact that Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Malta, Spain and the United Kingdom all signed, ratified and brought into force the provisions of the first European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage dating from 1969.

Themes of the study

For the purposes of this study the authors of the individual country chapters were drawn towards a number of themes to reflect issues that may reveal the commonality, or otherwise, of approaches to the protection of the architectural and archaeological heritage. The campaign, Europe, A Common Heritage, provides the appropriate vehicle and timing for the study.

The issues which follow are examined in relation to these themes bearing in mind that the interpretation and relative importance of the individual issues will differ according to the different countries and the state of progress in adopting policy and legal approaches that have been advocated by the conventions. Moreover, it must be remembered that legal tools are not the only means to resolve issues and that there is a plethora of guidelines, recommendations and charters which have been developed in an international context.

Definition of the heritage

The objective under this heading is derived from article 1 of the Granada Convention and article 1 of the Malta Convention: to consider the broad definitions of monuments, buildings, and areas of the architectural and archaeological heritage that are selected for protection and preservation in each country, and the measures adopted to signify their particular importance or ‘criteria for selection’.

The Granada Convention defines the architectural heritage according to three groups: monuments (buildings and structures), groups of buildings, and sites – those having conspicuous historical, architectural, archaeological, artistic, scientific, social or technological interest. In the Malta Convention it is specified that the archaeological heritage ‘shall include structures, constructions, groups of buildings, developed sites, movable objects, monuments of other kinds as well as their context, whether situated on land or under water’. There is no specific ‘interest’ category except to say that this heritage should be regarded as ‘a source of European collective memory and as an instrument for historical and scientific study’.

It is accepted that terms used in practice may vary from those used in the conventions, although they may still be within the spirit of the definitions contained therein.

Moreover, while the conventions do not specify an association (although it may be inferred) with the natural environment, where historic/cultural landscapes, parks or gardens are associated with the immovable heritage these may be relevant. In this context, the ICOMOS Florence Charter on Historic Gardens has considered such associations and such an association may be relevant to current laws and other policy statements that define these monuments.

In defining architectural assets to be protected, the full extent of the protection regime is a relevant consideration. This raises the question as to whether the protection regime applies, in the case of buildings, to the whole building or just to its external envelope, and whether other attached structures or other objects within the associated grounds or some other defined protection zone exists, and whether ‘fixtures’ or movable items within the building or monument are included within the protection regime. Moreover, the ‘setting’ or context of an architectural monument may have relevance. In relation to complexes, groups of buildings, or ensembles or sites different criteria for the scope of protection, as compared to single monuments, are likely to apply. Furthermore, other factors considered within the scope of protection may include items such as open spaces, parks, gardens, trees, ancient street patterns, other monuments and whether area-based forms of protection exist according topographically definable units such as historic quarters, reserves or other area-based protection mechanisms.

In relation to the archaeological heritage the Malta Convention considers the need for the protection of monuments and areas and the creation of archaeological reserves. The convention also considers the idea that sites defined for protection may include those where perceived remains, as well as known remains, exist. This then raises the question whether the mechanism for defining items to be protected covers the situation of the discovery of archaeological remains by chance (in other words, whether there is a system of mandatory reporting or mandatory protection).

For both the architectural and archaeological heritage the criteria for selecting monuments for protection, as well as the existence of any levels or categories of protection, may vary within law or policy statements.

Identification of the heritage

Article 2 of the Granada Convention and articles 2, 6, 7 and 8 of the Malta Convention suggest appropriate approaches and requirements for the use of inventories and recording methods for the immovable heritage. These have been further developed in the Core Data Index to Historic Buildings and Monuments of the Architectural Heritage (1995) (and further highlighted in Recommendation R (95) 3 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on ‘co-ordinating documentation methods and systems related to historic buildings of the architectural heritage) and the Core Data Standard for Archaeological Sites and Monuments (Council of Europe, 1999) or other methods for recording the immovable heritage.

The methods and procedures established and operated to identify and record the immovable heritage through schedules, lists, inventories or other records will vary according to the documentation and information that is included within the record, whether the record has a legislative basis, and as to how it is used in the protection and preservation process. The assembly of records may also be by different methods: by survey of towns or areas or by national survey.

For some countries the inventory may have been completed many years ago and the process will just require updating but for other countries the process of identifying the heritage may have only been partially completed. As knowledge about the heritage is not static there is likely to be a process by which records are updated.

The preservation and protection of the heritage

Articles 3, 4 and 5 of the Granada Convention highlight the need for statutory protection measures including appropriate supervision ansd authorization procedures to cover positive and negative aspects of preservation policy including repair, reuse, control over alteration or demolition of buildings and otherwise to prevent damage. The reuse of existing buidings is another consideration particularly in terms of how a new use may impact upon the historic integrity of an architectural asset. Moreover the idea of finding new uses for buildings is now widely accepted as a positive way of preserving the architectural heritage. This, however, will be dependent upon the flexibility of a structure to accept change without damage integrity and also on questions of financial viability.

In the case of ensembles, groups of buildings and sites the regulation of development that may have an impact upon the setting or character of such assets, articles 3, 4 and 6 of the Malta Convention consider the need for authorization and supervision of excavation and other archaeological activities including research work, the conservation and maintenance of the archaeological heritage (preferably in situ), rescue archaeology, and for the storage of remains which have been removed from their original location. The movable nature of the archaeological heritage is further considered in articles 10 and 11 in terms of the need to control the illicit traffic of assets. The importance of this issue internationally is also reflected in the Council of Europe’s European Convention on Offences relating to Cultural Property (1985a) (the ‘Delphi Convention’ has still not come into force for want of enough ratifications, despite being a highly comprehensive legal document), and the UNESCO (Paris) Convention (1970), European Community Directive of 1993 and the Unidroit Convention (1995).

The problems associated with the development of sites of potential or known archaeological remains is considerd in article 5 of the Malta Convention which deals with the integrated conservation of the archaeological heritage (see below).

Conservation philosophy

The foundation for an internationally accepted conservation philosophy is the ICOMOS Venice Charter of 1964 although the writings of John Ruskin and William Morris and others in the nineteenth century and the Athens Charter of 1931 have helped to devlop concepts and have influenced thinking in many different countries. Other charters and recommendations such as the ICOMOS AUSTRALIA Burra Charter and the ICOMOS Nara Document on ‘Authenticity’ have further helped to provide a basis for developing a philosophy of approach to conservation activity which conventions, through their legalistic nature, are less able to do. These have undoubtedly influenced the formulation of laws and, perhaps more appropriately, policies and attitudes. However, there remains considerable differences in terms of approach and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Belgium

- 3 Czech Republic

- 4 Denmark

- 5 France

- 6 Georgia

- 7 Germany

- 8 Ireland

- 9 Italy

- 10 Latvia

- 11 Malta

- 12 The Netherlands

- 13 Spain

- 14 United Kingdom

- 15 Review

- Index