- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Applied Communication Theory and Research

About this book

This volume provides a comprehensive examination of the applications of communication inquiry to the solution of relevant social issues. Nationally recognized experts from a wide range of subject areas discuss ways in which communication research has been used to address social problems and identify direction for future applied communication inquiry.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

FUNDAMENTAL VIEWPOINTS

| CONCEPTUAL ISSUES | 1 |

DAN O’HAIR

Texas Tech University

GARY L. KREPS

Northern Illinois University

LAWRENCE R. FREY

Loyola University of Chicago

How can theories of communication competence be transferred to organizational settings? What are the communication needs of the elderly or the handicapped and are these needs being met? Must women adopt traditional male communication patterns to succeed in business? Do training programs really make managers more effective in communicating with their subordinates? Which communication strategies should doctors use to get patients to comply with prescribed treatment regimen? Should parents let their children watch violent cartoon programs if these programs lead to aggressive communication behaviors? What role does interpersonal communication play in assimilating foreigners into a new culture?

Each of these questions addresses an important problem, or potential problem, in the real world. Furthermore, each question asks how communication principles or theories can be applied to solve a potential problem. This book is about how researchers conduct applied communication research. Applied communication research is the use of theory and method to solve practical communication problems. Applied communication research focuses on the identification and solution of communication problems that are salient to interested parties.

Applied communication research thus serves the needs of those who use communication in practical ways. Although applied research may well advance questions about theory and methodology posed by communication scholars from within the discipline, the primary purpose of applied communication research is to use theory and methodology in order to understand how communication works within particular settings to solve specific problems.

In this chapter, we examine the conceptual issues that serve as the foundation for applied communication research. We start by exploring in some detail the differences between basic and applied research. We then give an overview of the development of applied communication research. Next, we explore some of the requirements for conducting good applied research, with a primary focus on the importance of using theory to guide research. We conclude this chapter by providing an overview of how the remaining chapters address important theoretical and methodological issues facing applied communication researchers and practitioners within a variety of settings.

BASIC VERSUS APPLIED RESEARCH

Scholars in numerous disciplines recognize that there are two types of research. The first is basic or pure research, which tests theory, and the second is applied, which solves practical problems. Basic research in communication, and other social sciences, conforms to the model proposed by Parsons (1959) in which the goal of social science is to discover the laws that aid in explaining and predicting human behavior. Basic communication researchers, therefore, use research methods to test hypotheses, or predictions, derived from theories. They view their role in the inquiry process as discovering “laws of communication.” Berger and Calabrese (1975), for example, maintained that one law of communication is that “all communication reduces uncertainty.” They developed a research program to show that whenever we communicate, we reduce uncertainty about ourselves, others, and/or the situation.

Not all scholars use the terms basic and applied, but the terms that are used differentiate between these two types of research based on their purposes and goals. Coleman (cited in Lazarsfeld & Reitz, 1975), for example, used the terms discipline and policy to distinguish between these two forms of research. Discipline research advances knowledge of a scientific discipline, whereas policy research suggests guidelines and courses of practical action for actors or agents. Tukey (1960), on the other hand, viewed the differences between basic and applied research from a very pragmatic perspective by using the terms conclusion-oriented and decision-oriented. Conclusion-oriented research describes efforts that contribute to the knowledge of the discipline, whereas decision-oriented research refers to efforts that attempt to solve practical problems.

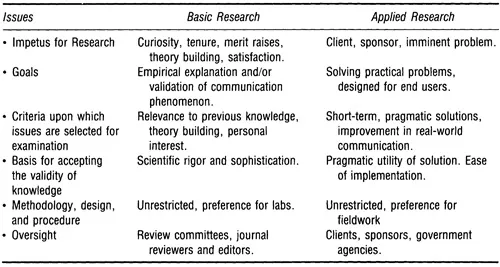

Regardless of which terms are used, there are some important differences between basic and applied research (see Table 1.1). For example, applied research typically is conducted under the sponsorship of a client, whereas basic research usually is not. Lévy-Leboyer (1988) as well as DeMartini (1982) referred to applied research as “client-centered” efforts. In applied research, clients or sponsors usually have very specific goals in mind for the research project and applied researchers are at the whim of those who pay their salary (or consultant fees). On the other hand, basic researchers typically have sole control over the purpose and design of the research.

Dubin (1976) maintained that because applied research typically is sponsored by clients, their concerns subsequently guide applied researchers. Preeminent among these concerns is the issue of change brought about by the research. Will change produce better results? Is there a strong rationale for suggesting change as a result of this research? In what direction should change go? These concerns function as contingencies that influence how applied researchers frame their research, conduct it, and report the findings to their clients, contingencies that are not the stuff that basic research is made of.

Dubin also argued that these concerns, in turn, impose a number of requirements on applied researchers. These requirements include the goals of research (i.e., clients focus on solving problems), validity issues (i.e., the validity of research for clients is related only to how useful the solution is), methodology and procedure (i.e., clients can dictate whether variables, such as salary increases, can be manipulated), and the implications for future research (i.e., clients often want follow-up research to assess changes). For example, this difference in sponsorship certainly affects what variables applied researchers study. Champanis (1976) argued that basic experimental researchers choose independent and dependent variables for their “ease of control and manipulation in the laboratory, not for any practical goals” (p. 730). In contrast, applied researchers enjoy no such luxury because the variables are selected based on the requirements of the problem and the needs of the clients. Champanis contended that, “the value of a piece of applied research is determined not by its adherence to the formal rules of the game of science, but by the stern criteria of: ‘Does it really work?’ ‘Does it make any practical difference?’ ” (p. 739).

TABLE 1.1

Variations of Basic and Applied Communication Research (adapted from Duncan, 1980)

Variations of Basic and Applied Communication Research (adapted from Duncan, 1980)

Basic and applied communication research also differ according to consumption rates of information generated by respective fields. Although it is difficult to predict the consumption rate of these two bodies of knowledge, the majority of communication research outlets cater to basic research. For example, there are relatively few equivalent trade, popular, and applied outlets for communication research as there are in disciplines such as management, marketing, psychology, home economics, and electronics. Perhaps the lack of publications outlets for communication practitioners and the general public account for the often misunderstood and erroneous assumptions made about the field of communication. There is little doubt that the general public or practitioners would be less enthused with reading communication research published in such journals as Communication Monographs, Human Communication Research, or Journal of Communication. Articles in the scholarly journals in the communication field appeal almost exclusively to an academic audience. Additional applied communication publication outlets surely would allow practitioners and the general public to take advantage of the research findings generated by both basic and applied researchers.

A more subtle, but important distinction between basic and applied researchers involves the career paths taken by each group. We are not arguing that all academic researchers conduct basic work and practitioners and applied researchers myopically study practical problems, but the predominant tendencies of these researchers do conform to certain behavior. It is often argued that academic researchers pursue basic research because publishing articles in a relatively small number of journals is a primary index of their professional success. The number of articles on academicians’ vitae is positively related to being perceived as successful. The rewards of such success are worthwhile: promotion, tenure, merit raises, sabbaticals, favorable teaching loads, and professional respectability. However, the knowledge that is accumulated in journals is frequently bland. In order that unique, exciting, important, and ground-breaking studies be published, a great deal of risk must be assumed by researchers, risks that may entail noteworthy results or those that are null. Because journals are not in the habit of publishing null results, academic researchers may have a tendency to be cautious, publishing studies with a high likelihood of significant results.

Applied researchers, on the other hand, view their success in terms of the number of clients served and problems solved. These problems are often very different from one project to the next and thus they are not as able to draw upon previous work as are basic researchers. Furthermore, applied researchers are held responsible for producing practical solutions and often must take enormous risks. If the risks taken are productive, a certain amount of gratitude is bestowed; however, if the risks taken prove disastrous, the livelihood of the risk-taker could be in jeopardy. Applied researchers are often asked to play the research game with a greater ante, more risk, and bigger stakes than basic researchers.

In spite of the apparent differences between basic and applied research, a number of similarities are obvious as well. Eddy and Partridge (1978), for example, contended that there is no real distinction between basic and applied research. They stated that:

There is no genuine theoretical or methodological distinction between “pure” and “applied” science. In popular thought, scientists engaged in pure research have little concern with potential uses of the results of their labor, and applied scientists are not concerned with making theoretical contributions. Yet, as any physician or biologist will testify, this neat distinction does not exist in actual scientific work. Physicians use theory daily in order to diagnose and treat clinical cases, and the results they obtain alter both theory and clinical practice. If this were not the case, they would still be using unicorn horn, leeches, and extract of human skull. Similarly, biologists utilize theory to develop pesticides permitting the control of fruit flies, and modify theory when fruit flies multiply in the laboratory. (p. 4)

In actual practice pure research and theory guide informed decision making in many different fields of endeavor.

Another similarity between basic and applied research is that both promote shared knowledge. Many times applied researchers are regarded as “social engineers,” researchers who only solve practical problems but do not really advance general knowledge. Janowitz (1971), however, contended that both basic and applied researchers extend our cultural understanding, and believed that a better model for applied research is that of “social enlightenment.” Applied research not only provides practical advice for members of a practical social system, but also helps achieve societal goals. Helping foreigners adjust to a new culture, for example, promotes the societal goals of closer international ties and less ethnocentrism, whereas analyzing presidential debates helps the electorate understand better the issues involved in a campaign as well as to judge the critical thinking skills of candidates.

To summarize, there are some important differences between basic and applied research with respect to goals, sponsorship, variable selection, knowledge transfer, and other issues (see Table 1.1). In the final analysis, there are, however, important similarities that also should be recognized. Basic and applied research are interdependent in the sense that neither type of research can be as strong without the influence of the other. Miller and Sunnafrank (1984) argued that, “theoretically-oriented pure research and socially directed, applied research, divergent images notwithstanding, are, at best, inseparable and, at worst, complementary rather than antagonistic” (p. 212). Perhaps by combining the relative advantages of basic and applied research several general shortcomings can be overcome and the overall quality of communication research can be enhanced. Basic research can benefit from the practical accountability that drives applied researchers to take risks with their work, generating research data with high payoff. Applied researchers can benefit from the high levels of scientific rigor evident in most basic research, necessitated by the blind review system inherent in most traditional publication outlets. By increasing the richness of pure research and the rigor of applied research, communication inquiry can be enriched.

THE GROWTH OF APPLIED COMMUNICATION RESEARCH

The development of applied communication research as a field generally parallels the development of the communication discipline itself. Early communication research was limited by a lack of theoretical foundation and lead consequently to a limited range of communication studies (Cohen, 1985). Unable to draw upon theories endemic to the field itself, early communication researchers consistently and generously borrowed theories and methodologies from related disciplines such as psychology and sociology to study human communication (Cohen, 1985; Pearce, 1985). Of course, these disciplines had become established by relying on theories and methods used within the physical sciences, such as biology and chemistry.

This reliance on other disciplines for theory and methodology in early communication research tended to create some “interdisciplinary conceptual addiction.” This addiction began with the assumption that the purpose of all research is to test predictions derived from theory. This was followed by a reliance on methodological procedures that were popular in the more well-established disciplines. Lewin (1943) labeled this methodological addiction “the law of the hammer.” Just as a child pounds everything in sight once he or she discovers a hammer, so too did researchers study everything in sight using their favorite methodological procedure. This tendency, however, ignored how appropriate the methodology was for studying the particular social phenomena of interest (Pearce, 1985). For example, this methodological addiction led researchers to rely extensively on experimental procedures whereby variables are manipulated in order to observe their effects on other variables. Although there certainly has been an attempt to break away from such methodological addictions, they still exist today. Hewes (1978), for example, has been particularly critical of researchers’ use of ANOVA procedures as a hammer to drive many an ill-advised nail.

These traditional methodological proce...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Preface

- PART I FUNDAMENTAL VIEWPOINTS

- Chapter 1 Conceptual Issues Dan O’Hair, Gary L. Kreps, and Lawrence Frey

- Chapter 2 Applied Communication Methodology Lawrence Frey, Dan O’Hair, and Gary L. Kreps

- PART II CONTEXTS

- ORGANIZATIONAL CONTEXTS

- Chapter 3 Industrial Relations Communication Carl Botan

- Chapter 4 Communication and Negotiation Deanna F. Womack

- Chapter 5 Organizational Communication Research and Organizational Development Gary L. Kreps

- EDUCATIONAL CONTEXTS

- Chapter 6 Training and Development for Communication Competence Gustav W. Friedrich and Arthur VanGundy

- Chapter 7 Application of Communication Strategies in Alleviating Teacher Stress Mary John O’Hair and Robert Wright

- SALES AND MARKETING CONTEXTS

- Chapter 8 The Dynamics of Impression Management in the Sales Interview Dale G. Leathers

- Chapter 9 Focus Group Research: The Communication Practitioner as Marketing Specialist Constance Courtney Staley

- Chapter 10 Audience Analysis Systems in Advertising and Marketing Ralph R. Behnke, Dan O’Hair, and Audrey Hardman

- LEGAL AND POLITICAL CONTEXTS

- Chapter 11 Application of Communication Research to Political Contexts Kathleen E. Kendall

- Chapter 12 Legal Communication: An Introduction to Rhetorical and Communication Theory Perspectives Steven R. Goldswig and Michael J. Cody

- HEALTH CONTEXTS

- Chapter 13 Applied Health Communication Research Gary L. Kreps

- Chapter 14 Health, Aging, and Family Paradigms: A Theoretical Perspective Mary Anne Fitzpatrick

- Chapter 15 Communication and Gynecologic Health Care Sandra L. Ragan and Lynda Dixon Glenn

- Chapter 16 Dentist–Patient Communication: A Review and Commentary Richard L. Street, Jr.

- Chapter 17 Communication Within the Nursing Home Jon R. Nussbaum

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Applied Communication Theory and Research by H. Dan O'Hair,Gary L. Kreps in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Lingue e linguistica & Studi sulla comunicazione. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.