![]()

Chapter 1

Urban Life

Diana Periton

Introduction

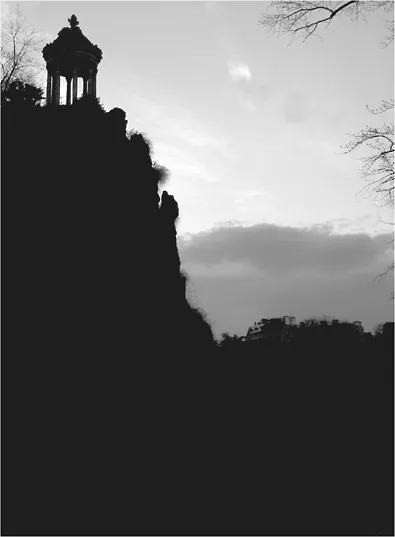

In Paris Peasant, published in 1926, Louis Aragon describes a visit he made with two friends, André Breton and Marcel Noll, to the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, on the north-eastern fringes of Paris. Chased there by boredom, they roamed through the park after dark on a spring evening. Both to them and to its nineteenth-century creators, the park seemed a place of constant experiment, a place heavy with possibility (see Figure 1.1).1

The park was a major ingredient in Haussmann’s ‘transformation de Paris’, built and planted in the 1860s on land next to the hangman’s gibbet that had been extensively quarried for gypsum and used as a dump for night soil.2 Haussmann described it as uninhabited wasteland, pervaded principally by noxious fumes. He proudly records that, once its metamorphosis had taken place, the 25-hectare site contained 5 kilometres of carriageways and footpaths, a specially pumped stream and a 32-metre waterfall, a lake with a temple-topped island reached by 2 bridges, extensive lawns, 3 chalet-restaurants, a belvedere, and the ‘inevitable grotto’. The chemin de fer de ceinture, Paris’ orbital railway, ran through a tunnel, then a ravine, across its eastern edge.3 The entry in the Paris Guide of 1867 reinforces and expands Haussmann’s facts and figures—5,940 square metres of path were gravel, 10,000 were sand; one of the two bridges was a suspension bridge with a span of 63 metres; the cliffs around the lake reached a height of 50 metres. It is also more forthcoming than Haussmann about the former inhabitants of the site, and the park’s intended effect on them:

In Aragon’s account, the area is a ‘test-tube of human chemistry, in which the precipitates have the power of speech and eyes of a particular colour’. Its thieves, bohemians and vagabonds, or, in his taxonomy, its rag-pickers and market gardeners (both dealers in human detritus) have mutated to become ‘postmen and middlemen’, the properly municipal subjects of Paris’ new XIXth arrondissement, annexed to the city along with the other outer arrondissements on 31 December 1859.5

Several pages of Aragon’s account are dedicated to the description of a bronze column that stood at a high point on the southern edge of the park (see Figure 1.2).6 By match-light, Aragon and his companions transcribed the information given on its four faces. Embossed figures declared it had been unveiled on 14 July 1883 ‘by kind permission of the municipal administration’. An inscription on the base gave the exact location of the column according to its height above sea level and that of the river Seine. Its cardinal points, the direction of and distance to the local town hall, as well as to several of Paris’ city gates, were also provided. The column recorded the postal addresses of the arrondissement’s nursery and elementary schools (and the number of places in each), of its municipal trade school, its hospital, markets both local and for the city as a whole, its religious establishments, police stations, post offices, tax collectors’ offices, squares and parks, railway stations, and the main routes (road, rail and canal) connecting it to ‘the exterior’.7 It also gave the total area of the arrondissement (566 hectares), the length of its streets, quays and boulevards (52.383 kilometres), the size of its population (117,885), and the number of dwelling houses—mostly full of rented rooms—it contained (3,162). Set into the faces of the column were a barometer, a thermometer and a clock.

The column thus acted both as a monument to its new arrondissement and as a recording device. The figures giving its geographical position in quasi-absolute terms endowed the more fleeting statistics of population with the apparent stability of cardinal points. Cast in bronze, the transient was literally monumentalized, given the fixity of the universal. Yet the very abstraction of the measurement of location, and its triangulation with the rest of Paris, simultaneously made the column relative to much larger systems of organization, its calibrations of time, air temperature and pressure further parameters of its contingent status. The details Aragon transcribed allow us to make conjectures about the population that inhabited this enduring but ever-changing setting: its potential educational status (through the provision of schools), its

morals (through the provision of religious and administrative institutions), its productive possibilities (through its markets and transport connections), its leisure activities and its health are hinted at—and we can, should we wish, calculate its density. Aragon saw the column as a cipher for the urban life it registered, a life that ‘no doubt has the local cinema as its social centre, an industrious and ill-rewarded [life]…, glowing with happiness and drunk with knowledge acquired at night school’.8

My own interest in the column’s inscriptions—and in Aragon’s decision to copy and preserve them—is in how these statistical hieroglyphs could be read as such a cipher. It is in how the collection and display of this data began to inform and to alter the conceptualization of Paris and Parisians, becoming not only a record but also a tool for the transformation of the city and its citizens. The range of countings carved and cast into the column could be found, amplified, in the Annuaires Statistiques de la Ville de Paris, published from 1880 onwards.9 These large volumes printed annual information on the state and distribution of Paris’ population (marital status, births, deaths, employment, etc., listed by arrondissement or quartier), on their economic and cultural activity (import and export of goods, taxes, savings accounts, municipal credit, the numbers of pupils at schools, colleges, etc.), and on their health (hospital admissions, distribution of poor relief). They also documented the city’s meteorological and geological conditions and its infrastructural systems. If the effect of the column was to still the data it displayed by gathering them to the hillside in the Buttes-Chaumont, once those data were understood as part of the constantly multiplied municipal statistics they became no more than a momentary reading of a fragment of the city, useful only insofar as they could be related to other information. Over time, the sheer quantity of readings collected, categorized and collated could be used to suggest relationships of cause and effect, to establish norms and to identify trends. Information concerning people could be juxtaposed with that on the properties of place, the fleeting with the long-lasting, until patterns of the city’s flux could be revealed.

In 1919, five years before Aragon’s excursion to the park, a government edict required all French towns and cities to draw up plans for their development and growth;10 in Paris, the École des Hautes Études Urbaines was founded, a ‘municipal laboratory of research’ whose remit was the methodical study of the factors influencing the formation and transformation of the metropolis.11 Through the standardization of the way information concerning the ‘social, demographic, topographic and climatic’ state of cities was gathered and displayed, and the consequent accumulation of comparative studies, the members of the new school hoped that the ‘general laws’ of an incipient ‘urban science’ might emerge.12

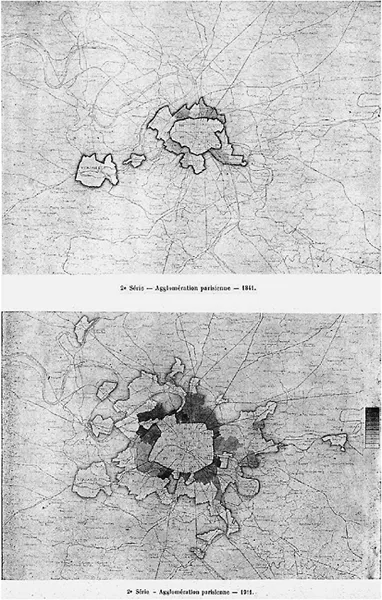

The inaugural article of the institute’s journal, La Vie Urbaine, indicated the kind of study proposed. Architect Louis Bonnier’s ‘La Population de Paris en mouvement’ consisted of two series of maps that chronicled the city’...