1 The Race Debate

This book is an attempt to grapple with a problem: the concept of race seems irredeemably corrupted but in some ways too valuable to do without. Now of course this isn’t the only race-related problem worthy of our attention. There are the venerable and important questions of racism, and of affirmative action and reparation. And questions of identity, and of the phenomenology and existential significance of race, have been resurgent topics for a couple of decades now. But the questions that motivate this volume excite different curiosities.

In 1897, W. E. B. Du Bois, faced with the question of whether people of African descent should assimilate or carve out a distinct community in the United States, and indeed on the world stage, gave his seminal lecture, “The Conservation of Races.” He argued, with characteristic power, not only that this population constituted a race, but also that it had something of a unique mission in the history of humankind, and thus he concluded that the elimination of racial differentiation would be a grave mistake. In the decades that followed, the soundness of racial thinking mostly became a topic to be studied by social and natural scientists, not philosophers. Indeed, with a few notable exceptions, racethinking was a largely dormant topic in philosophy until the 1980s. At that point, in a now-classic article, Kwame Anthony Appiah (1985; 1992) reexamined Du Bois’ conservationism. Dispatching Du Bois’ claims like so many badly outdated fashions, Appiah began a series of arguments in defense of the position that race is an illusion unworthy of our credence.

The desire to leave race behind is, of course, a dominant theme of the modern United States. In its least contestable form, it is the sentiment expressed in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s hope that his children be judged not “by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” But racial eliminativism makes a stronger claim than that. According to one political version of eliminativism, we should eliminate racial categories from all or most state policies, proceedings, documents, and institutions. Californians rejected such a proposal when in 2003 they voted to defeat the “Racial Privacy Initiative” (Proposition 54), which would have prevented most government agencies from collecting most types of racial data. Not one to be found in lock-step with Californians, George Will (2003), the prominent conservative columnist, has called for removing racial categories from the census. Sometimes, as with Will, political eliminativism is motivated not only by the claim that the way we think about race might be incoherent, but also by the rationale that eliminating racial categories will undermine other policies, such as affirmative action, which presuppose race. Indeed, in case there was any question, the brouhaha over eliminativism was that same year declared “a national debate” by the front page of the New York Times (Nov. 9).

A second, more sweeping form of eliminativism is the public version. Public eliminativism advises that we get rid of race-thinking not only in the political sphere, but in the entirety of our public lives, so that we neither assert nor recognize one another’s races. Finally, there is global racial eliminativism. The goal of this view is for us to eventually get rid of race-thinking not only in the political or even public world, but altogether. That is, even in our most private inner moments, race-thinking should go the way of belief in witchcraft and phlogiston: a perhaps understandable but hopelessly flawed, antiquated way of making sense of our world, a way of making sense that has no place in our most sophisticated story about The Way Things Are.

Now, in the wake of eliminativism’s rise, several respondents have tried to update and defend Du Bois’ basic position that race-thinking is worthy of conservation. These conservationists argue that, for various reasons to be examined within these pages, eliminating race-thinking would be a serious error. Thus, to take them out of order, the first of four main questions to be asked here, the question that will set much of our agenda in crucial respects discussed below, is

The Normative Question: Should we eliminate or conserve racial discourse and thought, as well as practices that rely on racial categories?

Those, anyway, are the conventional options. But, as is often the case with convention, this set of choices unnecessarily presents us with too few options. Or so I will argue. To turn over my first card, the normative position I will advocate is neither that we should out-andout eliminate race-thinking, nor that we should wholeheartedly conserve it, but that we should replace racial discourse with a nearby discourse. The basic idea to this position—what I will label racial reconstructionism—will be that we should stop using terms like ‘race,’ ‘black,’ ‘white,’ and so on to purport to refer to biological categories— as we currently use them. Instead we should use them to refer to wholly social categories.1

It is worth pausing for a moment to emphasize who ‘we’ are here. We are neither philosophers in particular nor academics in general. The Normative Question is whether all of us—everyone in our linguistic community—should keep or abandon racial discourse. Racial reconstructionism says that all of us should reconstruct our racial discourse. (Arguably racial discourse operates differently in different communities, so I will focus particularly on my linguistic community, which comprises competent English speakers in the United States. That said, I suspect that the arguments found below are relevant in many other communities as well.)

Whether we should be eliminativists, conservationists, or reconstructionists depends on two main considerations. First, a clutch of particularly salient evaluative considerations bear on this question: is racial discourse morally, politically, or prudentially valuable? For instance, if someone wants to be identified in a certain way, we arguably have a moral obligation—one that in some contexts can be overridden, to be sure—to identify them in this way. Obviously, racial identities are key components of some people’s self-conceptions, so moral value will have to be addressed here. A political question relevant to our discussion is whether race-thinking enables important policies for redressing racial injustices, or whether, as the biologist Joseph L. Graves (2001, 11) maintains, “the survival of the United States as a democracy depends on the dismantling of the race concept.” Less bold, but equally pressing and more common, is the political and moral claim that getting rid of race-thinking is part of a program of getting rid of racism (Appiah 1996, 32; Graves 2001, 200). Finally, abandoning race-thinking might be prudentially bad because doing so would disintegrate one’s individual identity; or it might be prudentially good because it allows us to pursue relationships that are difficult to pursue in a race-conscious world. And, of course, sometimes all of these values are thrown together into one mess. For instance, Graves (2001, 199) proposes an item that potentially impacts the putative political, prudential, and moral value of eliminating race-thinking: doing so will foster economic growth.

Before we get to those kinds of concerns, though, note a second relevant issue. If race is not real, then that generates one reason to get rid of racial discourse; if it is real, then that provides at least one reason to retain it. This presupposes a principle of epistemic value: if our beliefs should be sensitive to available evidence, then it is bad both to believe in something that evidently doesn’t exist, and to pretend that something that evidently does exist doesn’t. Other things being equal, you shouldn’t believe that an invisible goblin is typing these words for me so that I can relax and enjoy a beer. And other things being equal, you shouldn’t pretend that the moon doesn’t exist. If you’re with me on this—if you agree that, other things being equal, we shouldn’t believe in things that evidently aren’t real and that we should believe in things that evidently are real—then you’re with me in attributing importance to the second main issue to be discussed in this book, namely

The Ontological Question: Is race real?

When I first mention to civilian friends and students that many academics think that race is nothing but an apparition, one common reaction is incredulity. To such a way of thinking, the fact that each of us has a race, or multiple or mixed races, is unassailable. Any departure from conventional wisdom here might make academics appear to be unglued from the real world by sheer force of theoretical peculiarity. Whether or not the glue still holds will be an overarching theme in this book, as one of my main concerns—a concern that, I will argue, has been problematically ignored by many (myself included, at times)—is to account for, or at the very least confront in a richly informed way, common sense thinking about race.

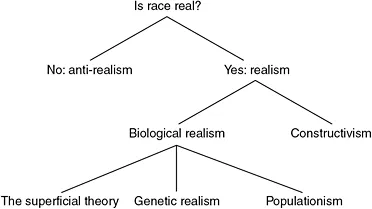

Though we will see below that common sense thinking about race is in fact strikingly complex, one fairly predominant element of the folk theory of race is that races are biological entities. Now there is more than one way that race might be biologically real. According to one understandable line of thought, we have skin colors and hair textures and facial features—we have, as biologists like to say, phenotypes (roughly, the macro-level expressions of our genotypes, our genetic makeup). If we can classify these phenotypes in a biologically kosher manner, then this is one way in which race might be biologically real. As it features something that can be superficially read off of the way we look, I’ll call this view the superficial theory. Another way in which race might be biologically real is not in terms of what we look like, but in terms of the genetic material that significantly determines what we look like—a theory we can call genetic racial realism. And then there is the source of our genetic material, namely our ancestry. So a currently popular wave of biological racial realism—populationism—holds that races are breeding populations or clusters of breeding populations, populations whose intra-group reproductive rate is sufficiently higher than their rate of reproduction with other populations, thereby ensuring genetic distance (and, usually, phenotypic difference) from each other over multiple generations.

As we will see, all three biological accounts of race have problems; but there is another branch of racial realism. Many contemporary realists, taking inspiration from Du Bois, maintain that race is not ultimately about biology at all. Instead of being a biological kind of thing, race is, on this alternative theory, socially constructed but real nonetheless. That is, race is real as a social kind of thing. This view, which I’ll call constructivism, holds that just as journalists or doctors are real but socially constructed kinds of people, so racial kinds of people are real but socially constructed—racial groups are real groups that have been created by our social practices, rather than by some biological process. Thus there are several different types of realism one might adopt (see Figure 1.1).2

Anti-realists generally think that race is not real because race purports, but fails, to be a biological kind. (Strictly speaking, though, this specific route to anti-realism is not required to be an anti-realist.) Obviously, each kind of realism is inconsistent with this anti-realist thought in its own way. Biological racial realists argue that anti-realism is wrong, because there is (they say) a biological reality to race. Alternatively, constructivists argue that race doesn’t need to be a biological kind of thing to be real; instead, it’s a socially constructed kind of thing. Thus on my way of defining the various theoretical positions, ‘constructionism’ names the view that the idea of race has been socially constructed, and to that extent it is neutral between anti-realism and the view that there are socially constructed races. This latter view is what I call ‘constructivism,’ and given the theoretical space it occupies, in order to know whether race is real we now have to answer the more basic question of what race is supposed to be. Is it supposed to be a biological kind (and if so, of what sort), or a social kind? Put somewhat differently, what are we purporting to talk about when we use words like ‘race’? This is the third main issue of contention that will be examined here:

Figure 1.1 The landscape.

The Conceptual Question: What is the ordinary meaning of ‘race,’ and what is the folk theory of race?

Rather than asking whether there is something in the world that matches up with our race-talk, this question just targets our race-talk itself: what kinds of things are we purporting to talk about when we talk about race? Are we trying to talk about real scientific kinds, as we do when we talk about, say, water or gold? Or are we purporting to talk about illusory kinds, as we did with, say, witches or phlogiston? Or, finally, could we be talking about some element of the socially constructed world, as when we talk about money or journalists or universities, which have no place, in and of themselves, in the world studied by natural scientists? Although, as we will see, what is in the world can sometimes help determine the meanings of our terms, the Conceptual Question is in the first instance a question about our racial discourse: What kinds of things are we purporting to refer to when we talk about race? At its core, this is simply a question about the meaning of ‘race’ and cognate terms. So the core part of the Conceptual Question is semantic. At its periphery, this question asks not about the ordinary meaning of ‘race,’ but about the folk theory of race; so the other part is folk-theoretical.3

It’s hard to overstate the importance of this question. If racial discourse does not purport to refer to a biological kind, then it will be a non-starter to argue that races are not biologically real. For, assuming that some things, such as universities or newspapers, are real not as biological things but instead as social things, race might be non-biologically real, too. If, however, racial discourse does purport to pick out biological categories, then when constructivists tell us that race is a social kind, they will be the ones who are talking about something else besides race, and their position would be the one that is irrelevant. It would be comparable to a debate about whether there were any real witches in colonial Salem, in which I insisted that there were, because some of Salem’s residents practiced Wicca. Aside from it being factually false that they practiced Wicca, you’d legitimately have a more basic conceptual complaint: those ‘witches’ are not the witches you’re talking about when you deny that there were any witches in Salem. In that context, by ‘witch’ one means the kind of person who casts spells and cavorts with the devil, so it is irrelevant whether anybody in Salem was practicing Wicca.4 In a parallel kind of way, once we know what race is supposed to be, we can figure out whether there is, in fact, any such thing.

That’s all by way of saying that the Conceptual Question is dialectically important: if we want to figure out an answer to the Normative Question, it seems as though we’re going to have to try to answer the Ontological Question, which means having to answer the Conceptual Question. Without minimizing this dialectical importance, we also should not forget that the conceptual truth about race has a substantial impact on the real world. Lucius Outlaw makes the point powerfully in the course of examining the nature and function of our racial categories:

this is more than an issue of philosophical semantics in racially hierarchic societies which continue to engage in efforts to promote and sustain forms of racial supremacy. In this context, racial categories take on the various valorizations of the hierarchy and affect the formation and appropriation of identities as well as affect, in significant ways, a person’s life-chances.

(Outlaw 1996a, 33)

And lurking behind the crucial Conceptual Question is one final issue. The Conceptual Question asks what racial discourse purports to talk about: anti-realists, such as Appiah (1996) and Naomi Zack (1993, 1995, 1997, 2002, 2007), think that ordinary racial terms (erroneously) purport to refer to some sort of interesting biological reality, while many of their opponents think that they purport to refer to some sort of social reality. But, then, if we’re going to try to figure out what racial terms purport to refer to, we need to know how to figure that out. That is, we must also answer

The Methodological Question: How should we identify the folk concept and theory of race?

As we shall see, one answer to this question is that in order to identify the folk concept of race, we should look at how experts have historically used racial terms. To turn my second card face up, I will argue that this methodology is, by and large, misguided. Instead, I will maintain that, for the most part, we should focus our attention squarely on how racial terms are used in contemporary mainstream discourse. Some people agree with that approach, and then proceed to engage in personal reflection—they reflect from the armchair, as we say—about the nature of contemporary folk racial discourse. I will also argue that the armchair-based approach is, while useful to an extent, insufficient. As an alternative, I adopt what I call the ‘experimental approach,’ which holds not only that the meanings of racial terms are, for our purposes, at least partially fixed by common sense, but also that we should inform our analysis of folk racial discourse with data gathered from actual empirical research conducted in a manner consistent with the practices of the social sciences. To be sure, I, like many, accept that we can also identify some of the content of our racial concepts while comfortably ensconced in the armchair. But even the data gathered from such armchair expedition...