![]()

Section II

Spirituality in Clinical Practice: Practice

![]()

5

The Practice of Spiritually Oriented Psychotherapy

Several changes and developments have occurred in the theory and practice of psychotherapy recently. Similar changes have occurred, and will continue to occur, in spiritually oriented psychotherapy. A review of these developments in conventional psychotherapy is useful in appreciating changes and the current status of spiritually oriented psychotherapy. This chapter begins with a description of developments in the practice of psychotherapy, and then describes similar developments occurring in the practice of spiritually oriented psychotherapy. This discussion serves as an introduction and overview of Chapters 6 through 10.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN PSYCHOTHERAPY

The past decade has witnessed a remarkable evolution in the theory, research, and practice of psychotherapy. Many, but not all, of these changes and developments are due to the accountability movement in health care. Increasingly, psychotherapy has become more focused, effective, and accountable. In 2005, the American Psychological Association formally embraced “evidence-based practice” in psychology. Evidence-based practice can be defined as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values” (Institute of Medicine, 2001, p. 147). It is broader than the concept of empirically supported treatment (described below) in that it explicitly considers client values and clinical expertise, that is, utilizing clinical skills and past experience to rapidly identify the client’s health status, diagnosis, risks and benefits, and personal values and expectations. Presumably then, competent and well-informed clinicians would develop and maintain enhanced therapeutic alliances; utilize best practices information; implement treatment tailored to match client diagnoses, need, and preferences; and monitor clinical outcomes (DeLeon, 2003). Parenthetically, it can be noted that an alternative model and statistical methodology to evidence-based practice has emerged. Called “practice-based evidence,” this rather sophisticated model has already improved clinical practice in health care (Horn & Gassaway, 2007), although it is has yet to be extended to the practice of psychotherapy.

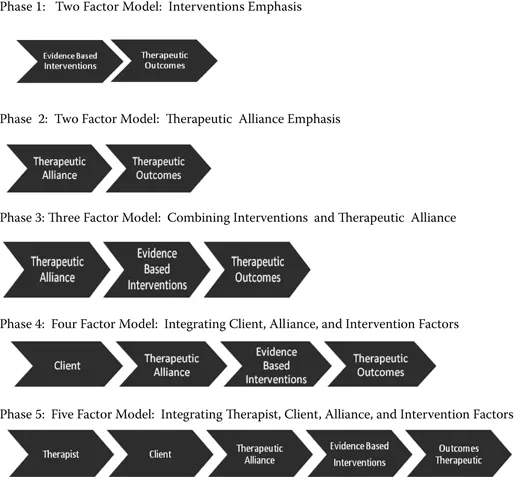

This section overviews five elements that reflect current theory, research, and practice, and their evolution. They are clinical outcomes, empirically supported treatment, the therapeutic alliance, client factors, and therapist factors. Figure 5.1 visually depicts the evolving role of these elements in the delivery of effective psychotherapy. Closely related to these elements are competencies and their role in training as well as in psychotherapy practice.

Clinical Outcomes

Outcomes have become the coin of the realm in psychotherapy today. Although processes are still considered important, the culture of accountability and the empirically based treatment movement have made clinical outcomes the central consideration in psychotherapy practice. Outcomes refer to the effects or end points of specific interventions or therapeutic processes. Two types of outcomes can be distinguished: immediate or formative outcomes and final or summative outcomes. Outcomes can be assessed in a pre-/posttreatment fashion or in an ongoing fashion, that is, by monitoring outcomes at each session. Research points to better outcomes when clinicians engage in ongoing monitoring than with pre-/postassessment or no formal assessment of outcomes (Lambert, Whipple, Hawkins, Vermeersch, Nielsen, et al., 2003).

Empirically Supported Treatment

In the 1990s the call for accountability in health care translated to demands for empirically supported treatment. Empirically supported treatments are interventions for which empirical research has provided evidence of their effectiveness. As health care costs were spiraling upward, clinician practice patterns were portrayed as the basic cause of waste, inefficiency, and escalating costs. As a result, health care systems and managed care plans moved to standardize care and specify rules for the provision of that care. The expectation was that clinicians—including psychotherapists—would only provide encounter-based, as opposed to relationship-based, services, and be able to demonstrate that these services were evidence-based and cost effective. This was the beginning of what has been called the empirically supported treatment (EST) movement in psychotherapy (Reed, McLaughlin, & Newman, 2002).

Figure 5.1 Factors and processes of effective psychotherapy: Evolution of models.

Psychology had already embraced evidence-based assessments and treatments as part of its long-held commitment to research on assessment and psychotherapy. In 1995 an APA task force was formed to address ESTs in psychotherapy. This EST task force identified both “well-established treatments” and “probably efficacious treatments.” Not surprisingly, most were short-term behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches, and longer term, more complex approaches, such as psychodynamic interventions, were not well represented (APA Division of Clinical Psychology, 1995).

The EST movement has significantly impacted psychotherapy practice. It provided managed care and insurance companies considerable leverage in controlling costs by restricting the practice of psychological health care. It also prompted local, state, and federal funding agencies to require the use of ESTs. The result is that ESTs are becoming established as the standard of care in psychotherapy. This conclusion is problematic as it is based on a questionable assumption. The assumption is that providing an EST is the necessary and sufficient condition for a positive therapeutic outcome. Phase 1 of Figure 5.1 visually depicts the relationship between the factors of ESTs and therapeutic outcomes.

Therapeutic Alliance

The APA Task Force on Empirically Supported Therapy Relationships (ESRs) was formed in 1999 in reaction to the earlier task force on ESTs. ESRs emphasized the person of the therapist, the therapy relationship, and the nondiagnostic characteristics of the patient (Norcross, 2002). The therapeutic relationship has consistently been the single most important variable in the now extensive literature on psychotherapy outcome research. An earlier meta-analysis by Lambert (1992) had found that that specific techniques—those that were the focus of the studies underlying the EST task force report—accounted for no more than 15% of the variance in therapy outcomes. On the other hand, the therapy relationship and factors common to different therapies accounted for 30% of the variance in therapy outcomes. Therapeutic alliance is a type of therapeutic relationship that encompasses three factors: the therapeutic bond between client and therapist, the agreed-upon goals of treatment, and an agreement about methods for achieving that goal or goals. The therapeutic alliance is described in more detail in Chapter 6. Phase 2 of Figure 5.1 visually depicts the relationship between the factors of therapeutic alliance and therapeutic outcomes.

Following the ESR task force report, it became increasingly clear that an either–or stance (i.e., ESTs or ESRs) was untenable. Instead, there was increasing acceptance that both ESTs and ESRs were operative in treatment outcomes. Phase 3 of Figure 5.1 visually depicts the relationship among the factors of evidence-based interventions, therapeutic alliance, and therapeutic outcomes.

Client

But that “both–and” understanding would soon be found to be shortsighted. A subsequent meta-analysis of the elements accounting for psychotherapy change (Lambert & Barley, 2001) found that the largest element accounting for change (40%) was due to extratherapeutic factors, also referred to as “client resources” or “client.” This finding was essentially the same as previously reported (Lambert, 1992). The client element includes several factors such as motivation and readiness for change, capacity for establishing and maintaining relationships, access to treatment, social support system, and other nondiagnostic factors. Phase 4 of Figure 5.1 visually depicts the relationship among the factors of evidence-based interventions, therapeutic alliance, client, and therapeutic outcomes.

Therapist

As useful as the Lambert research (1992, 2001) has been in understanding the elements contributing to psychotherapy outcomes, there was no apparent role for the therapist. It has long been observed that some therapists are much more effective than others. For years, terms like master therapist and supershrink have been used to describe the expertise of such therapists. Recently, there has been a surge of research on therapist factors that positively impact the client, the therapeutic alliance, and the implementation of therapeutic interventions, resulting in improved clinical outcomes (Sperry, 2010b). Phase 5 of Figure 5.1 visually depicts the relationship among the factors of evidence-based interventions, therapeutic alliance, client, therapist, and therapeutic outcomes.

Psychotherapy Competencies

In addition to the focus on these five elements is the role of competencies. Competency is the current zeitgeist in psychotherapy practice and training. Competency represents a paradigm shift in psychotherapy training and practice and, not surprisingly, has effected and will continue to effect change. Requirement standards are beginning to be replaced with competency standards, core competencies are replacing core curriculums, and competency-based licensure is on the horizon. The shift to psychotherapy competency is also an accreditation standard in psychiatry training programs now that requires that trainees demonstrate competency in three psychotherapy approaches. Training programs in clinical psychology programs have solidly embraced competencies, and marital and family therapy and professional counseling programs are poised to follow suit. Because competencies involve knowledge, skill, and attitudinal components, competency-based education is very different in how psychotherapy is taught, learned, and evaluated.

Six core psychotherapy competencies have been described. They are (1) articulate an conceptual framework for psychotherapy practice, (2) develop and maintain an effective therapeutic alliance, (3) develop an integrative case conceptualization and treatment plan based on an integrative assessment, (4) implement interventions, (5) monitor treatment progress and outcomes and plan for termination process, and (6) practice in a culturally sensitive and ethically sensitive manner (Sperry, 2009, 2010b).

DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PRACTICE OF SPIRITUALLY ORIENTED PSYCHOTHERAPY

Much of the professional literature on spiritually integrated psychotherapy is rather recent, and there are aspects of it that mirror developments in psychotherapy. Initially, this literature advocated for clinician sensitivity to spiritual/religious concerns. Then, it focused on incorporating spiritual/religious concerns in conventional psychotherapy approaches. That is not to say that there are no unique spiritually oriented approaches, because there are some, most notably transpersonal psychotherapy. However, most approaches are adaptations. Sperry and Shafranske (2005) have chronicled these approaches, of which two are traditional (psychoanalytic and Jungian) and ten are contemporary (cognitive behavioral, humanistic, interpersonal, etc.).

Currently, the literature on spiritually oriented psychotherapy is mirroring developments in psychotherapy with a focus on the elements of psychotherapy and the phases of therapy. The recent book by Aten and Leach (2009), Spirituality and the Therapeutic Process, has chapters on the therapist, the therapeutic alliance, assessment, case conceptualization, treatment planning, treatment implementation, and termination. The editors also acknowledge the importance of evidence-based practice in spiritually oriented psychotherapy. Next, this section addresses the relationship of spirituality to psychology, and the matter of competencies in spiritually oriented psychotherapy.

In professional psychology there is currently no consensus on either competencies or ethical guidelines for practice in which religious or spiritual perspectives and resources are explicitly integrated. Nevertheless, Richards (2009) has offered some preliminary considerations for psychologists who endeavor to practice spiritually integrated psychotherapy. Others have also articulated competencies and ethical guidelines for the practice of spiritually integrated psychotherapy to be considered (Gonsiorek, Richards, Pargament, & McMinn, 2009). However, this lack of consensus on competencies and codes leaves a void for psychologists practicing in this area. The development of clear guidelines poses a significant challenge and simultaneously offers an opportunity for this specialty field to develop and mature. Central to consideration of professional ethics is the area of professional competence.

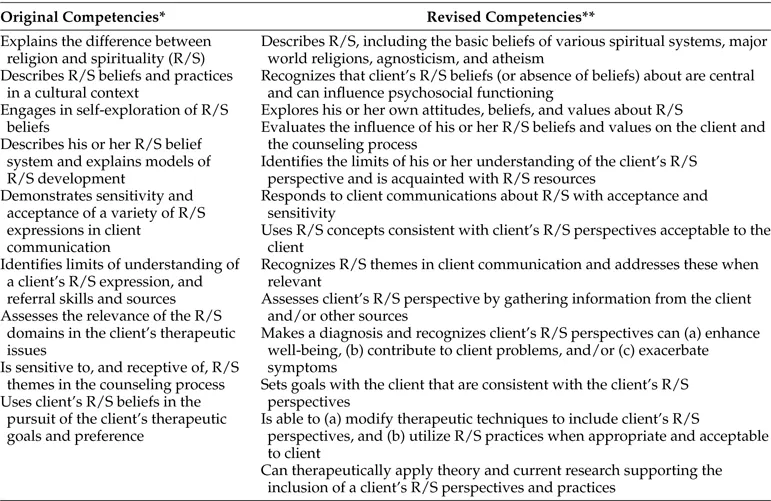

ASERVIC has specified and articulated a set of such competencies (Miller, 1999) and then offered a revision: “Competencies for Addressing Spiritual and Religious Issues in Counseling” (Cashwell & Watts, 2010). This document includes 14 competencies of which the first six are cognitive competencies (e.g., “can describe the similarities and differences between spirituality and religion”), and the last five are clinical competencies. These involve assessment, diagnosis, goal setting, and the utilization of spiritually sensitive treatment interventions. Table 5.1 compares the original and revised competencies.

Further development is required to articulate competencies and to establish clear standards for practice in each of the approaches presented in this chapter. Table 5.2 provides a tentative list of competencies for each approach. The tentative competencies were derived from Aten and Leach (2009) and Sperry (2010a).

Table 5.1 Evolution of Competencies for Addressing Spiritual and Religious Issues in Counseling (ASERVIC)

Derived and summarized from *Miller (1999) and **Cashwell & Watts (2010).

Table 5.2 Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy

1. Develop a therapeutic alliance that is sensitive to the spiritual dimension. |

2. Maintain the therapeutic alliance and deal with spiritual transference, countertransference, alliance ruptures, ambivalence, and resistance. |

3. Assess and diagnose, including the spiritual dimension. |

4. Incorporate the spiritual dimension in the case conceptualization. |

5. Incorporate the spiritual dimension in treatment planning and mutual goal setting. |

6. Implement spiritual and psychological interventions. |

7. Refer to, or consult with, religious/spiritual resources, if indicated. |

8. Monitor and evaluate overall treatment progress and outcomes on all dimensions, including the spiritual dimension. |

9. Incorporate spiritual dimension in the termination process. |

TERMS AND DESIGNATIONS

As a f...