Chapter 1

Introduction to the economics of transport

Learning Outcomes:

In the course of this chapter, you will learn about:

- The economic problem and its relevance to transport issues

- The factors of production that make up the production of all transport services

- The production possibility frontier and its illustration of the three concepts of scarcity, choice and opportunity cost

- The three market systems of the free market, the command economy and the mixed market

- The combination of agents that make-up transport markets

- The relevance of economic systems to the organisation and provision of public transport

- systems through a case study of the Glasgow conurbation.

INTRODUCTION

Most individuals, whatever their walk of life, have a basic need to travel from one location to another. Modern life as such is structured around accessing goods and services that lie outside of the immediate vicinity of the home. Transport services are thus required to gain access to employment, education, leisure activities, personal care/health services as well as access to retail outlets for household goods such as food, clothing, electrical goods, books, CDs and so on. The development of the world wide web, whilst shifting some of these activities to home-based pursuits, has not, as yet, succeeded in turning the majority of individuals into computer geeks that need to get out more! Transport therefore still has a key role to play in modern society. This importance is further reflected in the link between transport levels and economic growth. In the past this link has been very strong, as both passenger and freight transport play a vital role in the function of the economy, with strong growth normally associated with innovative transport solutions.

It is thus no great surprise that transport issues continue to feature strongly in the newspapers and television news. Issues such as congestion and the role of road pricing, the impact of traffic on the environment, the organisation of public transport services, the rise of low-cost airlines, the capacity of the rail network, or indeed ‘problems on the railways’ and so on, are constantly made reference to. All of these areas are subjects which the study of economics can help to shed considerable light on.

Transport is an area that has experienced major changes in recent years. For example, governments worldwide have become increasingly aware of the need to introduce effective ways of containing the use of the private car, both as a means of tackling congestion and as a result of the negative environmental impacts its use entails. Transport in general and the movement of passengers and freight bring with it considerable negative impacts in terms of air pollution, noise and visual intrusion. There has also been regulatory change and a reduction in state ownership of transport companies in all areas of transport, from the rail and bus industries, to freight companies, and in the aviation sector. This has tended to be on the grounds of increasing competition and improving efficiency. A book in transport economics seeks to shed light on these issues and outline why such reforms have been deemed to be necessary, as well as considering the overall economic problem of moving people and goods from one location to another.

The basic tools of the transport economist are drawn from what is known as microeconomic theory. This deals with questions such as what determines the demand for a particular journey or the demand for a particular mode of transport? What may happen to the level of congestion if a road pricing system is introduced? How can an airline operator charge passengers different prices for the same flight? What influences the level of competition within the bus sector? Questions of this nature tend to deal with individual units within the economy or certain sectors of the economy, such as the transport sector, rather than the economy as a whole. These are the types of questions transport economists are interested in and with the use of microeconomic theory this book aims to aid this under standing. Macroeconomics on the other hand is the field of study that concerns the whole economy, hence would examine issues such as the level of inflation, the level of unemployment or the size of the balance of payments. Outside of transport’s impact on economic growth, however, transport economists are less interested in these areas. Although clearly important, the main thrust of the book is to examine key microeconomic issues and only consider macroeconomic matters where this helps to give a wider overall perspective.

The book does not draw on one type of transport such as road, rail or air but uses examples from all modes. This is because most if not all of the economic principles covered are common to all modes. The approach taken is to reveal how microeconomic theory can be used to analyse the transport sector and come to a better understanding of the issues therein. As such, the knowledge learned should be transferable and used to analyse and understand other transport issues, not only those presented in this text. This is an important aspect of economic analysis and brings in the idea of the economic ‘toolkit’ of analysis, or even an ‘economic’ way of thinking. The text does not purport to outline ‘the answer’ or to even give an answer to all transport related topics, but rather should enable the reader to come to a better understanding of the underlying issues and principles concerning transport matters today. This first chapter will outline the nature of economics in terms of the economic problem and its relevance to the study of transport.

THE STUDY OF ECONOMICS AND ITS RELEVANCE TO TRANSPORT

What exactly is ‘economics’ all about and what has it got to do with transport? Most imagine economics is to do with money and all things financial. This can lead to some confusion, as it tends to paint a very grey picture as to the central issues with which the subject is concerned. What is required therefore is a clear definition to which various issues and topics can then be subsequently pinned. Economics is one of the social sciences, hence concerns the study of people and their actions. Therefore, whilst psychology studies how people structure their thoughts and motivations, sociology how people interact with each other (or don’t!), and anthropology the study of societies and how they function, economics is concerned with how societies cater for their material wants and needs. It is therefore about the production, distribution and use of society’s goods and services (to the maximum benefit of all). A rather trite example in a transport context therefore would be that it concerns who gets a Rolls Royce and who ends up with a 15-year-old mountain bike as their main mode of transport? Whilst trite, that definition does fairly clearly point to not only some critical transport issues but also the basic economic problem – there are not enough Rolls Royces to go around, hence some have to go without, the question being who will that be? This ‘scarcity’ of luxury motor cars can be applied to more general cases such as all private vehicles or all seats on a train during the rush hour, the difference being that some are more ‘scarce’ than others. As a result of this scarcity, ‘choices’ need to be made and each choice will come at a cost, known as the ‘opportunity cost’. The basic economic problem, and hence all economic issues, can therefore be related to these ideas of scarcity, choice and opportunity cost. Note at this stage no mention or reference has been made to money matters.

SCARCITY, CHOICE AND OPPORTUNITY COST

Scarcity is a concept that is normally associated with Third World countries, where a lack of rainwater and the subsequent failure of agricultural produce cause famine and drought. Scarcity however applies not only to Third World economies but all economies, whether Third World, developing or advanced. In simple terms individuals cannot have everything that they want because there is a finite limit on the resources that can be used to satisfy these ‘wants’. Any resource is therefore scarce, perhaps not at the margin as with the Rolls Royce example above or at the level of a basic necessity, but they are nevertheless scarce.

If individuals cannot have all that they want, then choices need to be made, and put simply every choice involves a cost. This will always be the next best alternative that could have had been selected when that choice was made. This is known as the opportunity cost of that decision. Thus if a particular society does not have sufficient resources to build both a new stretch of motorway and a new airport, it must make a choice between the two. If it chooses to build the motorway then the opportunity cost of the motorway is the airport that was not built. Opportunity cost therefore can be formally defined as the next best alternative forgone and is consequently not assessed using financial criteria.

These three concepts of scarcity, choice and opportunity cost can all be illustrated on what is known as a production possibility frontier.

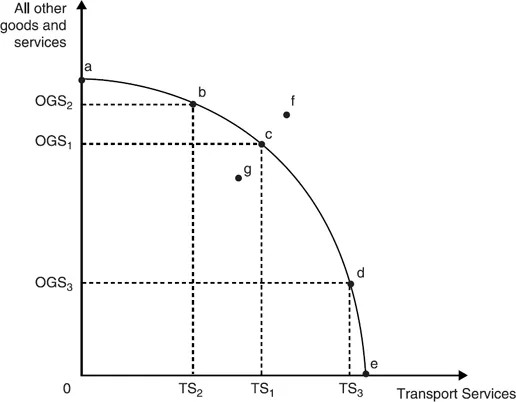

The assumption of the production possibility frontier is that only two products can be produced, thus in Figure 1.1 the choice is between either transport services or all other goods and services. Whilst these may be very general categories, they do nevertheless show the underlying principles. As resources are finite there is a maximum level or combination that can be produced which is shown by the actual production possibility frontier (PPF). Thus if all resources are put into the production of all other goods and services, point a on the PPF would be achieved, whilst putting all resources into the production of transport services would result in an output level at point e. Where some combination of the two is produced, this is shown by all the intermediate points between a and e, with b, c and d highlighted for illustrative purposes. Also shown are points f and g. As point f lies outside of the PPF it is thus unattainable with the level of today’ s technology, but may become attainable at some point in the future through advances in technology. Such advances would cause the whole frontier to shift outwards. Point g on the other hand lies inside the frontier, hence is attainable, but would represent a position of inefficiency as society is not utilising the maximum potential of its finite resources.

Figure 1.1 The production possibility frontier

If therefore these two commodities can only be produced in finite quantities, this leads into the first ‘decision’ to be made: namely what combination of the two to produce? If the choice was to produce at point c on the production possibility frontier, this would result in the production of TS1 transport services and OGS1 of other goods and services. Say however that some ‘decision’ was made to increase the level of other goods and services up to OGS2, then this increase would have to be at the expense of transport services. This is because all resources are being employed in the production of these two commodities; thus in order to increase one, the resources required to do so have to be found through reduced production of the other. This is akin to an airline company that may want to increase its frequency on a particular route with immediate effect, but in order to do so it will have to find the necessary aircraft from its other routes until in a position to increase the total fleet size.

Figure 1.1 therefore also illustrates the opportunity cost of such decisions. As a result of increasing production of other goods and services from OGS1 to OGS2, the production of transport services has fallen from TS1 to TS2. This reduction represents the opportunity cost. Note further if the level of other goods and services was to be increased again, say up to the maximum at point a, then an even larger quantity of transport services would have to be given up. The opportunity cost in terms of transport services is therefore becoming greater as the production of other goods and services increases. This is because at first the resources used in the production of other goods and services will be the most suitable; however, as production steps up it will have to increasingly use less suitable resources, i.e. those more suitable for the production of transport services. Hence ever larger quantities of transport services will have to be sacrificed. This again is akin to our airline example, where the airline will firstly use those aircraft from other routes that are the most suited to the purpose; however, further increases in frequency would have to be served by less suitable aircraft.

As any economy (country) cannot provide its citizens with all that they want, i.e. there is scarcity, a choice has to be made with regard to three basic questions –

- what to produce?

- how to produce it?

- and for whom to produce it?

The first we have already seen as it concerns the question of where on the production possibility frontier should production take place. How that output should be produced concerns the ‘best’ use or combination of resources to ensure that there is no inefficiency (as indicated by point g on Figure 1.1). Hence an example from the energy industries would concern what is the ‘best’ way to generate electricity – through coal-fired power stations, by nuclear fusion, through hydro systems, wind power, solar power or finally by burning natural gas? In some ways the answer to that question will be dependent upon the resources available, hence in a country with large coal reserves the normal practice would be through the first method. The last question concerns who gets the rewards arising out of the commodities produced, or more exactly how are the benefits of wealth creation to be shared out amongst the members of society. This is our key question above as to who gets the Rolls Royce and who gets the 15-year-old mountain bike. These three questions arise as a result of the basic economic problem – scarcity – hence, you can’t always get what you want. The mechanism used to address these three critical issues of what, how and for whom to produce is what would be referred to as ‘the economy’. This has led to the development of different economic systems or types of economies to answer these questions, and these can generally be classified as command, free market or mixed market.

Command, free and mixed market economies

A command economy is where the state, i.e. the government, directly addresses the three questions posed above. That is, the government decides what to produce, how it will be produced and who will receive the resultant output. In the past this has normally been centred on a system of plans, in which five-year plans are subdivided into one-year plans, then area plans of production, then by town, by company, by individual plant and so on down. The government also decides how the factors of production are employed. Factors of production are the resources that are used in the production process. All production processes can be broken down into three factors of production or basic inputs – land and raw materials, labour and capital. Land/raw materials and labour are fairly self explanatory as regards production resources, capital on the other hand is any equipment that is used in the production process. Thus a basic ship’s voyage is produced by a labour element (the ship’s crew), a capital element (the ship itself) and land/raw materials (the fuel used to power the ship and the natural environment in which it operates, e.g. the open sea or coastal waters). Under a command economy system, the state organises the factors of production to resolve the first two questions of what and how to produce, and distributes the resultant production on the basis of equity, i. e. if you work hard you reap the rewards. Note that in theory under such a system there is no need for any form of money, as goods and services are distributed on the basis of decisions by government or some other delegated central body. Such a system was in the past associated with the former communist countries in Eastern Europe; however, historically they have not solely been associated with the political left, as demonstrated by the German economy under the extreme right wing National Socialists from 1933 to 1945.

Today the relevance of studying such systems may appear to have completely disappeared with the collapse of the European communist states and their associated command economies in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Nevertheless, it gives the important theoretical perspective of the role of government in the running of the economy: it is key and central to the whole operation.

At the other end of the spectrum is the free market economy. In its most extreme form, a completely free market economy has no government input into the decisions of what, how and for whom to produce. Government’s only function is to provide law and order. Economic decisions are left purely to the market in the form of private buyers and sellers, with the price mechanism and the profit motive playing central roles in the operation of the whole economic system. The price mechanism transmits signals from the market to the various interested parties, with the underlying philosophy being that trade is never a zero sum game, as both parties (usually) benefit in any exchange. Added to this is the idea of consumer sovereignty, i.e. the consumer is king. In simple terms, if consumers want more of something they will go out and buy it, and this will cause the price of that commodity to rise. Thus through the price mechanism a signal is sent to producers that consumers want more of that particular product and driven by the profit motive they will produce more of it. Hence in Figure 1.1, where to produce on the production possibility curve is decided by consumers. If for example consumers express a desire for more transport services, then through their market actions, by for example showing a willingness to pay a higher price for them, producers will shift resources out of the production of other goods and services and into the production of transport services. Another far less esoteric view of this example is that some firms producing other goods and s...