![]()

1

Test Score Interpretation and Use

Carol A. Chapelle

Mary K. Enright

Joan M. Jamieson

Test users and researchers alike see test publishers as responsible for providing defensible and clear interpretations of test scores and encouraging their appropriate use. Accordingly, the TOEFL® revision was intended to result in test scores whose interpretation was transparent to test users and supported by “an overall evaluative judgment of the degree to which evidence and theoretical rationales support the adequacy and appropriateness” of their interpretation and use (Messick, 1989, p. 13). Attempting to develop theoretical rationales, designers of the new TOEFL began by exploring how theories of language Proficiency would serve as a basis for test design. This chapter summarizes issues that arose during this process, explains how the test designers shifted focus to the validity argument that justifies score interpretation and use to resolve these issues, and outlines the interpretive argument that underlies the TOEFL validity argument.

LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY

Members of the TOEFL revision project believed that language proficiency theory should form the basis for score interpretation. This belief was consistent with a view prevalent in educational measurement in the early 1990s that a theoretical construct should serve as the basis for score interpretation for a large-scale test with high-stakes outcomes (e.g., Messick, 1994). However, articulating an appropriate theory of language proficiency is a divisive issue in language assessment: Agreement does not exist on a single best way to define language proficiency to serve as a defensible basis for score interpretation. Discussion of how to do so for the TOEFL drew on and contributed to an ongoing conversation in the field of language assessment (e.g., Bachman, 1990; Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Chalhoub-Deville, 1997, 2001; Chapelle, 1998; McNamara, 1996; Oller, 1979). Most language assessment specialists would agree that there is no single best way of defining language proficiency that the TOEFL project could adopt.

Two Common Beliefs

Language assessment specialists would also tend to agree on at least two other issues. One is that limiting a view of language proficiency to a trait such as knowledge of grammatical structures, knowledge of vocabulary, or reading is seldom an appropriate basis for the types of interpretations that tests users want to make. Instead, Proficiency typically needs to be conceptualized more broadly as the ability to use a complex of knowledge and processes to achieve particular goals rather than narrowly as knowledge of linguistic form or a skill. Such abilities would include a combination of linguistic knowledge (e.g., grammar and vocabulary) and strategies required to accomplish communication goals. In other words, the knowledge of language is not irrelevant, but it is not enough to serve as a basis for interpreting test scores because test performance involves more than a direct reflection of knowledge. From the earliest modern conceptualization of language proficiency (e.g., Canale & Swain, 1980), some sort of strategies or processes of language use have been argued to be essential (Bachman, 1990; McNamara, 1996).

Most applied linguists would also agree that language proficiency must be defined in a way that takes into account its contexts of use because contexts of language use significantly affect the nature of language ability. In other words, the specific linguistic knowledge (e.g., grammar and vocabulary) and the strategies required to accomplish goals depend on the context in which language performance takes place. As Cummins (1983) pointed out, second language learners can be proficient in some contexts (e.g., where they discuss music and movies with their peers orally in English), but they lack Proficiency in other contexts (e.g., where they need to give an oral presentation about Canadian history to their classmates in English). A conceptualization of language proficiency that recognizes one trait (or even a complex of abilities) as responsible for performance across contexts fails to account for the variation in performance observed across these different contexts of language use. As a consequence, virtually any current conceptualization of language proficiency in language assessment attempts to incorporate the context of language use in some form (Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Chalhoub-Deville, 1997; Chapelle, 1998; McNamara, 1996; Norris, Brown, Hudson, & Bonk, 2002; Skehan, 1998).

These two points of consensus about language proficiency constituted the beliefs held by TOEFL project members throughout discussion of the theoretical construct that should underlie score interpretation. Both of these beliefs had a common implication—that the new TOEFL should include more complex, performance-type assessment tasks than previous versions of the TOEFL had. While providing some common ground among participants, these beliefs were difficult to reconcile.

Two Approaches to Test Design and Score Interpretation

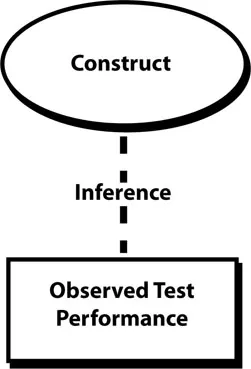

In educational measurement in the 1980s and 1990s, two different conceptual frameworks emerged for test design and score interpretation. Messick (1994) characterized these opposing frameworks as competency-centered and task-centered. In competency-centered assessment, a theoretical construct of language proficiency underlies score interpretation. As illustrated in Figure 1.1, the construct is conceptually distinct from the observed performance and is linked to the performance by inference.1 A construct is a proficiency, ability, or characteristic of an individual that has been inferred from observed behavioral consistencies and that can be meaningfully interpreted. The construct derives its meaning, in part, from an associated theoretical network of hypotheses that can be empirically evaluated. The competency-centered perspective was therefore consistent with the belief held by the members of the TOEFL project that the type of inference to serve as the basis for score interpretation should be one that links observed performance with a theoretical construct of ability consisting of knowledge and processes.

FIG 1.1 Inference in competency-centered assessment.

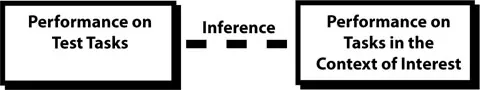

From a task-centered perspective, the basis for score interpretation is the context of interest to the test user, and therefore this perspective is consistent with the second point of consensus among language assessment specialists— that the context of language use must be taken into account in conceptualizing score interpretation. From the perspective of performance testing, Wiggins (1993) claimed that judgments about whether students have the capacity to put their knowledge to use can be made only from observation of their performance on tasks that require students to perform in highly contextualized situations that are as faithful as possible to criterion situations. Answers are not so much correct or incorrect in real life as apt or inappropriate, justified or unjustified—in context. A task-centered approach to assessment focuses on identifying the types of tasks deemed important in the real world context and developing test tasks to simulate real world tasks as much as possible within the constraints of the test situation (Messick, 1994). Because the context in which performance occurs serves as a basis for score interpretation, the inference is the link between performance on test tasks and performance on tasks in the context of interest. See Figure 1.2.

FIG 1.2 Inference in task-centered assessment.

Because of the different inferences assumed by competency-centered and task-centered testing, the two perspectives generate two separate and seemingly incompatible frameworks for score interpretation. Assuming different inferences underlying score interpretation, each approach draws on different types of evidence for justifying the inferences that support score interpretation. Whereas researchers working within competency-centered testing look for evidence supporting the inferential link between test scores and a theoretical construct (e.g., textual competence), those working in task-centered testing establish the correspondence between test tasks and those of interest in the relevant contexts (e.g., reading and summarizing introductory academic prose from textbooks alone in a dormitory study room).

Difficult Issues

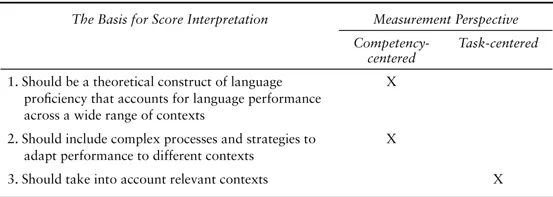

The presuppositions and beliefs of the members of the TOEFL project fell across the two perspectives for test design and interpretation as summarized in Table 1.1. The presupposition that a theoretical construct of language proficiency should form the basis of score interpretation is consistent with competency-centered assessment, which assumes that theoretical constructs should be defined as underlying knowledge structures and processes that are responsible for performance across a wide range of contexts. The belief that the construct should consist of a complex set of abilities is also encompassed within the conceptual framework of competency-centered testing even though complex, goal-oriented abilities or strategies are necessarily connected to contexts of language use. They are therefore not as universally applicable as the traits that underlie score interpretation in competency-based testing, but such abilities are theoretical constructs and therefore do not fit within task-centered assessment. The belief that context influences language performance and that it must therefore be included in score interpretation fits within a task-centered approach.

TABLE 1.1

Intersection between Beliefs about the Basis for Score Interpretation and Approaches to Test Design

Test designers’ discussion of language proficiency resulted in something of a stalemate that required them to look to a more inclusive and detailed approach for the justification of test score interpretation and use. A unified view of validity, in which multiple types of validity evidence were seen as necessary to support the interpretation and use of test scores, was well established in the field by 1990 (e.g., Cronbach, 1988; Messick, 1989). But only recently have researchers in educational measurement considered in detail how this evidence can be synthesized into an integrated evaluative judgment (Messick) or validity argument (Cronbach) for the proposed interpretation and use of test scores. Such an approach is being developed by researchers such as Mislevy, Steinberg, and Almond (2002, 2003) and Kane (Kane, 2001; Kane, Crooks, & Cohen, 1999). Their conceptual approach entails developing two types of arguments: First, an interpretive argument is laid out for justifying test score interpretation. An alternative to defining a construct such as language proficiency alone, an interpretive argument outlines the inferences and assumptions that underlie score interpretation and use. Second, a validity argument is ultimately built through critical analysis of the plausibility of the theoretical rationales and empirical data that constitute support for the inferences of the interpretive argument.

INTERPRETIVE ARGUMENTS

The retrospective account of the TOEFL project given in this volume is based upon the current view that a validity argument supporting test score interpretation and use should be based on an overall interpretive argument. Development of such an interpretative argument requires at least three conceptual building blocks. The first is a structure for making an interpretive argument. More specifically tied to the TOEFL interpretive argument, the second requirement is a means of including both the competency and the task-based perspectives as grounds for score interpretation and use. The third is a conceptualization of the types of inferences that can serve in an interpretive argument for test score interpretation and use.

Argument Structure

Current approaches toward developing interpretive and validity arguments (Kane, 1992; 2001; Mislevy et al., 2002, 2003) are based on Toulmin’s (1958, 2003) description of informal or practical arguments, which characterize reasoning in nonmathematical fields such as law, sociology, or literary analysis. Informal arguments are used to build a case for a particular conclusion by constructing a chain of reasoning in which the relevance and accuracy of observations and assertions must be established and the links between them need to be Justified. The reasoning process in such informal arguments is different from that of formal arguments in which premises are taken as given and therefore do not need to be verified.

Mislevy et al. (2002, 2003) used Toulmin’s argument structure to frame an interpretive argument for assessment, as illustrated in Figure 1.3. In such an assessment argument, conclusions are drawn about a student’s ability. Such conclusions follow from a chain of reasoning that starts from data such as an observation of student performance on a test. In Mislevy’s terms, conclusions drawn about test takers are referred to as claims because they state the claims that the test designer wants to make about a student. The claim in Figure 1.3 is that the student’s English-speaking abilities are inadequate for study in an English-medium university. Claims are made on the basis of data or observations that Toulmin referred to as grounds. In Figure 1.3, the observation that serves as the...