Countdown to Creative Writing

Step by Step Approach to Writing Techniques for 7-12 Years

- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Countdown to Creative Writing

Step by Step Approach to Writing Techniques for 7-12 Years

About This Book

Developing children's writing abilities boosts their confidence, creates enjoyment and relevance in the task and cultivates a range of decision-making and problem-solving skills that can then be applied across the curriculum. The Countdown series provides all the support you need in helping children to improve their prose, poetry and non-fiction writing.

Countdown to Creative Writing is a comprehensive and flexible resource that you can use in different ways:

- 60 stand-alone modules that cover all the essential aspects of writing a story

- countdown flowchart providing an overview showing how modules are linked and how teachers can progress through them with the children

- photocopiable activity sheets for each module that show how to make the decisions and solve the problems that all writers face along the road from first idea to finished piece of work

- teachers' notes for each module with tips and guidance including how modules could be used as stand-alone units, but also with suggestions for useful links between modules, and curriculum links

- a self-study component so that children can make their own progress through the materials, giving young writers a sense of independence in thinking about their work

- 'headers' for each module showing where along the 'countdown path' you are at that point.

In short Countdown to Creative Writing saves valuable planning time and gives you all the flexibility you need - teachers might want to utilise either the self-study or 'countdown' aspects of the book, or simply dip into it for individual lesson activities to fit in with their own programmes of work.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Modules 14–10

Part 1 Getting ready to write

General guidance

- At the outset, when pupils are doing their first thinking, they sometimes don’t realise it’s fine to have an idea about the end or the middle of the story first. While we (rightly) encourage pupils to make sure their stories have a ‘strong start’ it can result in an overemphasis on the beginning with a corresponding lack of creative energy later on. Pupils sometimes ‘run out of ideas’ because they believe they can’t think of anything else to say, they become bored and dispirited and quite frequently abandon the project.

- The beginning-middle-end template often becomes a habit of thought over time, locking pupils’ thinking into a restrictive linear way of envisaging story. This manifests itself in what I call the ‘and-then syndrome’. The syndrome can be recognised by the following characteristics in the pupil’s writing:

- Simple linear B-M-E narrative structure.

- Little or no manipulation of time in the form of flashbacks or other ‘chronological jumps’ (for example ‘A year went by …’ or ‘Three weeks later …’).

- Often a corresponding lack of movement in space. By that I mean the writer’s (and subsequently the reader’s) attention stays with one character throughout, even if the story is written in the third person.

- A noticeable lack of creative energy later in the story. This shows itself in various ways, such as the pupil actually repeating ‘and then’ often sometimes coupled with an abrupt and unsatisfactory conclusion. One also finds less zest in the writing coupled with little innovation: the plot limps along and one can imagine the writer struggling and wanting only to fill the required space on the page.

Module 14

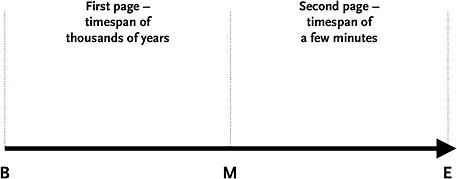

Timespan

Inside and outside

Getting your head around time

- Earth’s people had slept

- great wars had devastated the planet

- whole continents had been laid to waste

- global superpowers had battled

- civilisation’s last resources.

- the hiss of air being pumped into the sleep chamber

- the opening of Andros’s eyes

- glass being smashed

- the glint of the knife in the mutant rat’s hands.

Activities

Module 13

Pace

How fast do you go?

How can you control pace?

- Build in some action-packed incidents.

- Use shorter sentences and short paragraphs.

- Write brief scenes with frequent changes of scene and viewpoint. Several things happening at once can make a story zoom along, but you have to keep control of the action and be careful not to confuse your reader.

- Use strong powerful adjectives and punchy verbs (words ending in ‘ing’ also quicken the pace). Use adverbs that indicate speed and suddenness. ‘Suddenly’ is a good example.

- Use phrases that suggest speed—in no time at all/in the blink of an eye/all of a sudden/without warning …

- Include plenty of quick-fire dialogue, but balance dialogue (speech) with description. There is nothing worse than pages and pages of speech by itself—except pages and pag...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Overview – How to use the book

- 60 Getting started

- 59 A few tips

- 58 Good writing habits

- 57 A writer’s rights

- 56 What is a story?

- 55 Having ideas

- 54 Ideas for a reason

- 53 Plot bank

- 52 Plot, characters and background

- 51 Inspiration

- 50 All of your senses

- 49 Metaphors

- 48 ‘Sounds as it says’

- 47 The structure of a story

- 46 Forms

- 45 Diary

- 44 Play format

- 43 Letters, texts and other ideas

- 42 Basic narrative elements

- 41 Sub-elements

- 40 Tips on planning

- 39 The six big important questions

- 38 Narrative lines

- 37 Genre

- 36 Fantasy

- 35 Science fiction

- 34 Horror

- 33 Crime/thriller

- 32 Romance

- 31 Animal adventures

- 30 Further ideas for genre

- 29 Audience and purpose

- 28 Characters

- 27 Names

- 26 SF and fantasy names

- 25 Picture a person

- 24 A bagful of games

- 23 Character ticklist

- 22 Personality profile

- 21 Settings

- 20 Visualizations

- 19 Map making

- 18 Place names

- 17 Titles

- 16 Word grid

- 15 Mix and match

- 14–10 Getting ready to write: part 1

- 9–4 Getting ready to write: part 2

- Review

- Bibliography