1 Understanding the Concept

Regrettably, theorizing about gatekeeping has not been in large supply, a problem we explore in a later chapter. The selectivity inherent in the communication process lacked a theoretical focus until Kurt Lewin (1947a) provided the metaphor of the gatekeeper and David Manning White (1950) gave the gatekeeper life under the pseudonym of Mr. Gates. The gatekeeper metaphor offered early communication scholars a framework for evaluating how selection occurs and why some items are selected and others rejected. It also provided a structure for the study of processes other than selection, such as how content is shaped, structured, positioned, and timed.

KURT LEWIN’S “THEORY OF CHANNELS AND GATE KEEPERS”

The first pairing of the terms gatekeeping and communication apparently came in the posthumous publication in 1947 of Kurt Lewin’s unfinished manuscript “Frontiers in Group Dynamics II: Channels of Group Life; Social Planning and Action Research” in the journal Human Relations. At the time of his death, Lewin was director of the Research Center for Group Dynamics for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, but he had earlier held appointments at other U.S. universities, including the University of Iowa (Marrow, 1969).

A second version of the “frontiers” manuscript appeared as part of the chapter “Psychological Ecology” in the 1951 book Field Theory in Social Science, an edited and synthesized collection of Lewin’s work.2Field theory refers to one segment of German psychology at about the time of the First World War, with the concept of

field having been borrowed from physics (Bavelas, 1948). One group of psychologists wanted to reduce the person and the environment into isolated elements that could be causally connected. Lewin, trained as a physicist, was more aligned with the group that “attempted to explain behavior as a function of groups of factors constituting a dynamic whole—the psychological field” (Bavelas, 1948, p. 16). The field consists of both the person and the surrounding environment. Field theorists look at a problem in terms of the dynamic interplay between interconnected factors rather than as relationships between isolated elements. Lewin was working on a way to express psychological forces mathematically, using “geometry for the expression of the positional relationships between parts of the life space, and vectors for the expression of strength, direction, and point of application of psychological forces” (Bavelas, 1948, p. 16). Lewin argues that psychologists can mathematically define the forces shaping people’s behaviors, in much the same way that forces such as gravity are defined by physicists.

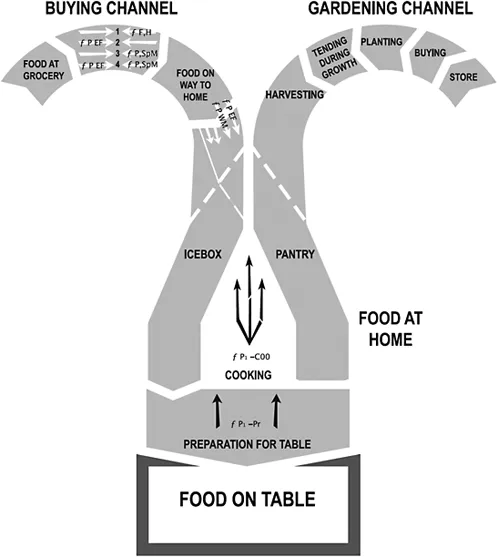

Lewin wrote primarily about changing a population’s food habits, but his purpose more generally was to understand how psychologists can effect widespread social changes (1947a, p. 146). In his analysis of food eating, he began with the assumption that not all members of the population are equally important in determining what is eaten. Therefore, social change can best be accomplished by concentrating on those people with the most control over food selection for the home. Lewin thought of food as reaching the family table through channels. One channel is the grocery store, where food is purchased, but other channels also carry food, such as the family garden. Figure 1.1 illustrates how channels may be subdivided into sections, and the beginning of each section represents an action point. In the grocery channel, for example, the first three sections include discovering the food at the grocery store, buying it, and transporting it home. Food traveling along the garden channel begins with buying seeds or plants from a garden store and planting them. As the fruits and vegetables grow, some are weeded out, some are eaten in the garden by insects or children, and others fail from lack of fertilizer or water. Of the fruits and vegetables available to the household, only some are harvested; others languish on the vine or branch.

At this point, the grocery and garden channels combine into the kitchen channel. Storage decisions must be made (in the refrigerator or pantry?) for each food unit. As a consequence, some foods are “lost” in the deep recesses of the refrigerator, and others are wasted because they were incorrectly stored (does an opened jar of jelly have to be refrigerated?). Next, the cook decides whether (and how) to cook the food or to pass it through raw to the next section, preparation for the table. Finally, the cook places and stages the food on the table, ready for the family to eat (Lewin, 1947a, p. 144). At each section, food can be rejected or accepted, but even more importantly the process of moving down the channel changes the food. Vegetables are cut up, steak is prepared rare or well done, potatoes are fried or baked. We conclude, therefore, that gatekeeping involves not only the selection or rejection of items, but also the process of changing them in ways to make them more appealing to the final consumer. If we think of the final decision point as whether the food is eaten, we can see that even the colors of food items and how they are placed on the platter can affect whether they are eaten. Even their environmental context is important. A nice tablecloth, candles and low lighting create a context in which food may be more appreciated.

Figure 1.1 Lewin’s gatekeeping model shows how food items pass through two channels on their way to the family table. Channels are divided into sections, and at the front of each is a gate that regulates movement through the channel. Forces on both sides of the gate can either constrain or facilitate the movement of items through channels.

Source: Lewin (1947a, p. 144).

The entrance to a channel and to each section is a gate, and movement within the channel is controlled by one or more gatekeepers or by a set of impartial rules (Lewin, 1951, p. 186). For example, some food never gets into the grocery channel because of the buying decisions or policies of the store manager/gatekeeper, and each shopper/gatekeeper walks down some rows and so misses some items. From among those items that the shopper sees, some items are bought and others rejected, perhaps because of a family rule about eating meat. Although most purchased food is transported successfully to the household (transportation section), part of it may be eaten along the way and some perishables may be ruined in transit. Once in the home, the cook/gatekeeper evaluates whether the food should be cooked, how to prepare it, and whether to offer it to the family.

An important aspect of Lewin’s theory is his idea that forces determine whether an item passes through a gate. With gates controlling access to all sections within all channels, it is clear that forces are at work throughout the channels. These forces work for or against selection and also influence the processing of items. When a grocery shopper considers a food item for purchase, both positive and negative forces influence whether the food is put in the cart. Attractiveness is a positive force that encourages purchase, whereas high expense is a negative force that makes the shopper less likely to buy the item. Lewin also contends that forces can change polarity (from positive to negative or the reverse) once an item passes through the gate. A negative force on one side of the gate can become positive on the other and actually facilitate movement of the item through subsequent gates. In addition, Lewin hypothesized that forces vary in strength, with stronger forces being more likely to move an item through a gate. Therefore the concept of force is central to the theory: Forces occur throughout the channel, they range from positive to negative and can change polarity, plus they vary in strength between and within items.

For example, the decision to buy an expensive cut of meat may be difficult, because the decision is constrained by the high cost of the meat—It’s very expensive; should I buy it? Once bought, however, the negative force can become positive and create a strong probability that the shopper makes sure that the meat will successfully pass through the remaining gates and reach the table—It’s so expensive; I must take extra care to transport, store, cook, prepare, and serve it carefully and well. Because the forces before and following a gate differ in strength and polarity, whether an item passes through the channel depends on the forces on both sides of each gate.

In Figure 1.1, arrows show how forces act to facilitate or constrain the passage of items either within a channel section or on both sides of a gate. Forces are designated in italics; for example, fP EF1 represents the force associated with the attractiveness of the food within the buying section, and it helps the food move through the next gate into the transporting-to-home section. Other forces are also present within the buying section, however, such as the force fP EF2, which represents the expense of the food item. As Figure 1.1 shows, the high-expense force yields to a countervailing force of equal strength against spending money, fP, SpM, and thus it is unlikely that the food item will pass through to the next section. Foods that do get into the “on way to home” section leave it with a force against wasting money, fP WM, which helps ensure that the food passes into the appropriate icebox or pantry section.

Lewin believed that this theoretical framework could be applied generally:3 “This situation holds not only for food channels but also for the traveling of a news item through certain communication channels in a group, for movement of goods, and the social locomotion of individuals in many organizations” (Lewin, 1951, p. 187). This was the inspiration for studying the flow of information using the gatekeeping model.

Although the terms channel, section, and gate imply physical structures, it is clear that they are not objects at all but represent a process that describes why and how some items pass on their way, step by step, from discovery to use. Sections correspond to things that occur in the channel, such as the copy-editing process. Gates are decision or action points. Gatekeepers determine both which units get into the channel and which pass from section to section, exercising their own preferences and/or acting as representatives to carry out a set of pre-established policies. They also decide whether to make changes in the item.

DAVID MANNING WHITE AND “MR. GATES”

The first communication scholar to translate Lewin’s theory of channels and gatekeepers into a research project was David Manning White, who learned about Lewin’s work while serving as his research assistant at the University of Iowa. White persuaded a wire editor on a small-city newspaper—whom he called “Mr. Gates”—to keep all of the wire copy that came into his office from the Associated Press, United Press, and International News Service during one week in February 1949. Mr. Gates also agreed to provide written explanations of why each of the rejected items was not used—and about 90 percent of the wire copy received was not used. This allowed White to compare the items actually used with the aggregate of stories that the wire services transmitted during the week.

The selection decisions, according to White, were “highly subjective” (1950, p. 386). About a third of the time, Mr. Gates rejected stories based on his personal evaluation of the merits of the item’s content, especially whether he believed it to be true. The other two thirds of items were rejected because there wasn’t enough space for them or because other similar ones were already running.

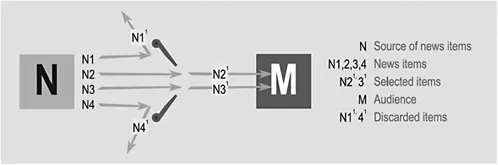

Figure 1.2 is a visualization of White’s gatekeeper model (McQuail & Windahl, 1981, pp. 100–101). News sources (N) send news items to the media gatekeeper, who turns some away (e.g., N1 and N4) and sends others (N21 and N31—the superior numerals indicating that the news items are changed as they pass through the gate). A 1966 replication of White’s study by Paul Snider, with the original Mr. Gates, yielded much the same result. Although Mr. Gates was 17 years older and could choose only from one wire service, his story selections were still based on what he liked and on what he thought his readers wanted. He used fewer human-interest stories in 1966 but more international war stories, either showing more of an interest in hard news or reflecting the increasing amount of news about the Vietnam War. Mr. Gates defined news as “the day by day report of events and personalities and comes in variety which should be presented as much as possible in variety for a balanced diet” (Snider, 1967, p. 426).

Figure 1.2 David Manning White’s vision of gatekeeping.

Source: McQuail and Windahl (1981, pp. 100–101).

OTHER GATEKEEPING MODELS

White’s study encouraged many scholars to use the metaphor of gatekeeping, if not the full theoretical model. In 1965 Webb and Salancik said that the gatekeeping metaphor was used in many journalism research studies, and that it was an example of how “journalism research has moved appreciably toward a more rigorous approach to data” (p. 595). In one of these studies, Gieber (1956) looked at 16 newspaper telegraph editors’ selections of wire copy, and his conclusion was quite different than White’s. Whereas White concluded that the gatekeeper’s personal values were an important determinant of selection, Gieber described the editor as being “caught in a strait jacket of mechanical details” (1956, p. 432) that keep personal values from having a major influence on the selection of stories. Gieber proposed that personal subjectivity was less important in gatekeeping than structural considerations, including “the number of news items available, their size and the pressures of time and mechanical production” (1964, p. 175). The wire editor, he said (1956), is essentially passive, and the selection process is mechanical. He concluded that the organization and its routines were more important than the individual worker’s characteristics.

A year later Westley and MacLean (1957) proposed what became a popular model of mass communication. They combined the idea of gatekeeping as an organizational activity with Newcomb’s (1953) psychological model of interpersonal communication, termed coorientation. For Newcomb, every communicative act involved transmitting information about an object; the simplest model involved person A sending information about object X to person B. Westley had been Newcomb’s student and saw that the ABX model could be modified to study mass communication.

Westley and MacLean expanded the model by adding C to designate a mass media channel (the organization as gatekeeper). In their model, X indicated a message, and f designated feedback (Westley & MacLean, 1957, p. 35). Arrows in Figure 1.3 show the flow of information (whether news items or feedback) from one actor to another. It can flow between A and B through C, or it can skip the mass media channel entirely. The model also shows that some information is rejected and some changed by media gatekeepers. Westley (1953) saw news judgment as the essential explanation of gatekeeping decisions.

As in the model describing White’s study, not all information bits are successful in passing through the media channel to the audience. B receives a subset of the messages available to C and may provide feedback both to C and to A about the messages. In this extension of Newcomb’s model, Westley and MacLean point out that at an...