CHAPTER 1 The New Towns in a new light

The Centre: Milton Keynes, 2008.

The twentieth century was a time of huge social and technological change. The industrialisation that began in the nineteenth century accelerated in the twentieth. The industrialisation of warfare created atrocious mass carnage and persecution in two world wars, the execution of which drove new technological advances. The motorcar, radio, radar, the passenger jet, electronics and computers all saw huge advances during this time. They changed the way we live, and gave the British economy new opportunities in the post-war world. The urban development of the twentieth century reflects these changes.

The dawn of the century found the new industrial towns and cities of the nineteenth century densely overcrowded. Death and sickness rates were high in urban areas and traffic congestion increased as motorcars replaced horse-drawn vehicles. As suburbs spread outwards along transport links, they further added to the sheer numbers of people working in the centre. The response to these urban problems in the aftermath of the Second World War was a deliberate policy of ‘decentralisation’, encouraging people to move out of Britain’s cities. The bombed-out city centres were to be rebuilt and entirely new towns were to be created, both using new designs specially adapted for this new modern age.

The post-war New Towns Programme was the largest public house building programme of its kind. The places created now house more than two million people in settlements with populations ranging from ten thousand to as high as a quarter of a million each. The towns were to be built by dedicated development corporations, receiving loans from the government to get construction underway, to be repaid at current rates of interest. This town-scale mortgage loan, originally set for repayment over 60 years, was then supplemented by ad hoc subsidies and other sources of income. The last of the loans were repaid in 1999, with the final sum estimated at £4.75 billion (CLG, 2006: 31).

It was a massive undertaking. The creation of entire towns required new infrastructure including roads, water, sewers, electricity and gas networks, as well as large volume construction for housing, commercial and civic buildings. People who needed houses were housed, and companies seeking to expand were able to build new premises outside of the restraining conditions of the dense inner cities that were often in cramped and deteriorating conditions. Since then, surplus land assets in the New Towns have generated a further £600 million profit for the government (House of Commons, 2002a). In the long term, it can be argued that the New Towns have proven to be value for money as the investment made has been recouped.

However, the towns that were created—more than thirty in total—have long been an unfashionable topic for urban theorists and journalists. They have often been derided for having unspectacular architecture or dismissed as a failed social experiment, with headlines such as ‘Fallen Utopia’ (BBC, 2007) or ‘Brave New World’ (Guardian, 2007). Their reputations have been tarnished by pockets of extreme deprivation and a vicious spiral of decline, and in some cases, chronic problems of maintenance, widespread abandonment and ultimately demolition. The New Towns have long ceased to be regarded with the attention they deserve. The aspirations they originally set out to meet resulted in some cases in a total reversal of fortunes.

Yet, between the late 1940s and the late 1970s, the New Towns not only attracted the most talented and creative professionals of the day, but also inspired similar urban development around the world. Many senior figures in British architecture and urbanism worked on the New Towns and much of the published literature, dating from the 1960s and 1970s, celebrated their achievements. Comparing current construction programmes with those that existed when the New Towns were proposed and built, a number of questions arise. How did such a large programme of construction come to be? How was it organised? How did things start to go wrong? What are the lessons for similar programmes today?

A number of reports from think tanks, campaigners and internal government research projects have sought transferable lessons for today. These reports have often been aimed at an audience of policy-makers, and focused on the immediate development plans, such as the Growth Areas. Academic research papers or books have assessed the long-term effectiveness of the stated aims of the policy, or examined specific issues such as transport. Various books describing the growth of individual towns or the memories of early residents have been published over the years. The success of the stated aims of the policy has been scrutinised. The story of each town over the years has also been subject to their unique circumstances. Yet, many attempts at researching the New Towns have been hampered by a historic failure to record basic information. A government research unit set up to follow the progress of the towns at the start of the programme in the late 1940s was scrapped after only 18 months. Later, in 1992, the government ceased to classify the New Towns as a specific area of public policy, regarding them as no different from other towns, disguising their socio-economic performance from public statistics (House of Commons, 2002a).

This book attempts to provide a fresh review of the New Towns by taking a broad look at their historical origins and subsequent development. Where did the New Towns Programme originate, and what ideas were used? What was the experience like of building the towns and later living in them? What are their prospects today, and what does their experience tell us about future urban development? Each town was truly a product of its time: designed according to the latest ideas of urbanism, adapted to modern realities, and aiming to solve problems that had become intractable in Britain’s older towns and cities. They broke with the past, rejecting traditional street and building layouts in favour of experimental new design ideas. They responded to the view that the old, historic urban form was failing in the face of technological change.

The need for this response was clear and unambiguous. Britain’s existing towns and cities had indeed become polluted, unhealthy and dysfunctional—unfit for the modern world. Created in the era defined by the arrival of cars and television, the story of the New Towns demonstrates the changing character of urbanism in the twentieth century. The ‘brave new world’ that Aldous Huxley had written about in 1932 was that of the ever-growing North American culture of consumer capitalism. Changes in the way that people live—or rather, the ways they were expected to live—are carved into the urban fabric of the New Towns. From the walk-to-work neighbourhoods of the first generation, to ‘full motorisation’ later, the New Towns show how movement profiles have changed. The expectations and opportunities for entertainment, the role of shopping in British society and the approach to green space, are all subject to a radical rethink. The reform of the old status quo, informed by debates in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, can be compared to similar debates today about how to make better places, and address the challenges of sustainable development. The early twenty-first-century guidelines for urban design practice, determining the layout of buildings, streets and public spaces are in marked contrast to the approaches taken then (DETR and CABE, 2000). Will new waves of reform in the principles of urbanism and architecture go a similar way?

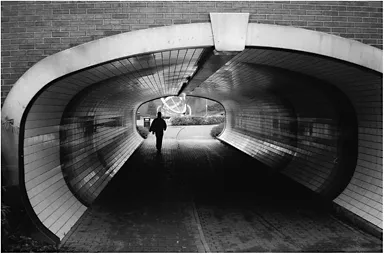

The New Towns pioneered the use of car-free routes and centres.

New Towns in the future

Major new urban developments today, from large-scale town expansions to the Government Eco-Towns Initiative, also seek to attract new thinking. This is necessary because of fundamental concerns that contemporary urban Britain has again become deeply dysfunctional, this time in terms of environmental sustainability. Yet the words ‘new town’ have become so much associated with the post-war New Towns Programme, and these towns have attracted such bad press in recent times, that these words have become anathema in discussions on building more new towns today. Instead they are euphemistically rephrased as new settlements or completely re-branded and reconceived as Eco-Towns. Whatever their label, strong environmental performance must be paramount in all new developments, as well as existing settlements, in order to address the enormity of climate change and other negative ecological reactions to industrialisation.

Progressive house building in Willowfield, Harlow, early 1960s. Copyright: Museum of Harlow.

Changes in lifestyle throughout the twentieth century reveal the way that society can be rapidly transformed, in ways that are extremely difficult to predict. How can designers and planners make plans that will still be robust in twenty years’ time, when society clearly will experience considerable change in twenty years? This change is certain, but the exact nature of change will be inherently unpredictable. The lesson for today must be to anticipate change as inevitable and design in inherently flexible and adaptable ways. The story of the New Towns reveals the actions of the first generation of people to work in the new British planning system. This new legal environment sought to guarantee that urban development was planned in the public interest. Yet this new planning system, based on predicting future needs for the first time, had to respond to accelerating change in the twentieth century.

The period of time it took to develop the New Towns is also a salient lesson for built environment professionals today. Although the programme started in 1946, legal challenges delayed initial work and an economic crisis in 1948 stalled progress almost completely. Construction of the first towns only really got underway in 1952—six years after the programme had been started. In 1955 the situation slumped again, rising to a peak of productivity in 1957, then declining to its lowest point in 1964. Between then and 1970, with a new generation of towns commissioned, prospects were looking up, before collapsing again after 1972 (Osborn and Whittick, 1977). With the global economic crisis of 2008, the most severe since the Wall Street Crash of 1929, plans for sustainable communities may take a similarly long time to come to fruition. Major publicly funded construction works during the Great Depression helped stimulate economic activity, as they may well do so again. The lesson is that there may be little benefit in being too contemporary in design aspirations, given the length of time from drawing board to the capping-off of construction.

As the New Towns have passed the fortieth, fiftieth or sixtieth anniversaries of their designation, they have entered phases of renewal. The nature and quality of the places that resulted highlights the challenge of such ambitious urban growth. Some of these challenges are unique to the New Towns whilst others affect all similar urban development in the UK dating from this post-war era. These include the design qualities of industrial estates and housing estates built on the edge of countless towns, the road infrastructure that often isolates their town centres and the modern precincts or shopping developments in the inner cities or the urban fringe. Bristol, Coventry, Gloucester, Plymouth, Leeds, Birmingham, Swindon, Huntingdon, Thetford or Canterbury, all display the problems of such post-war urban development. All these places will be forced to address this legacy in their future development.

Nowadays, the fact that our streets tend to fill up with traffic would be regarded as a fault of the traffic rather than the street. Transport planners of the post-war era assumed that the circulation of vehicles through the arterial roads of the country was vital for the economic health of the nation. The impact of ring roads, one-way systems, roundabouts and underpasses has led to towns suffering from a breakdown in the circulation of human movement, affecting the economic life of town centres. The urban structure of historic towns is inherently more sustainable as they have a finer grain of buildings, creating a built environment that is easy to change incrementally, and a scale of development that is designed to be walkable and hence has low car-dependency.

Local leaders in British cities such as Birmingham have been overcoming political obstacles and remodelling their cities to a more human-scale and less car-centred form. The stranglehold of the post-war ring-road infrastructure has been removed by a series of strategic interventions around the city centre. The large-scale post-war housing estate at Castle Vale has been completely demolished and replaced by a more traditional pattern of streets and buildings (Mournement, 2005).

The New Towns face different challenges in terms of their scale and urban character, and different economic circumstances. Yet there are clear parallels. The story of the New Towns also cannot be separated from that of other towns in Britain. The ubiquitous urban features of the latter half of the twentieth century—multi-lane highways, multi-storey car parks, shopping malls, high-rise housing—all made their first appearance in Britain via the New Towns Programme, which in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War provided a major platform for innovation.

The ambition was impressive, and the need was great. The New Towns Programme was a vital response to Britain’s damaged condition in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. Factories that were once the vanguard of industrial progress, overloaded to mass-produce weaponry, were collapsing through lack of maintenance. A staggering 500,000 homes had been destroyed and a further 500,000 damaged by enemy action, of which the majority were in London (Hennesey, 1992: 104).

Set alongside emergency pre-fabricated housing and new construction in the inner cities, the concept of the New Town provided an ambitious, large-scale solution, yet it did not appear from nowhere. The origin came from attempts in the late Victorian and Edwardian era to address industrial pollution and poor housing conditions created in the nineteenth century. As such, many basic design ideas applied in the New Towns were devised far earlier than the post-war era. The New Towns Programme presented a vision of the future, but many of its key concepts were born a generation earlier. Understanding the long campaign that prompted the creation of the New Towns Programme is vital to understanding how these towns came to be realised. Following their evolution over time highlights the range of factors that influenced their relative successes and failures by the end of the twentieth century.

Problems lie in the disparity between intention and achievement. The New Towns were intended to produce healthier places to live, carefully planned to meet the needs of their future residents. This meant demonstrating the latest approaches in architecture and urban design, with extensive car-free areas and traffic-free routes. The same sentiments are echoed today in the call for sustainable communities. Stern warnings are provided by the wind-swept, economically depressed pedestrian shopping precincts and car-free housing estates of the New Towns, inspired by experimental layouts in Scandinavia and the USA. In the new quest to build zero-carbon communities it is vital that lessons from the New Towns are not lost.

The New Towns were intended to showcase the work of a new generation of architects, as well as the pioneering new profession of town planner. They aimed to create low levels of outward commuting by ensuring that local jobs were available to local residents. Marketing strategies were developed to attract businesses, which also helped to create a strong sense of identity for the towns. The employment of arrivals officers to help new residents settle in quickly emerged as a valuable way to monitor the success of the new communities. In later stages, brand new approaches to community consultation were pioneered. New places that offered a better quality of life than before were created, and new opportunities and new lifestyles did result. As the first report of the New Towns Committee declared,

It is not enough in our handiwork to avoid the mistakes and omissions of the past. Our responsibility, as we see it, is rather to conduct an essay on civilisation, by seizing an opportunity to design, evolve and carry into execution for the benefit of coming generations the means for a happy and gracious way of life.

(cited in Gallagher, 2001)

The parallels with the urban regeneration of recent years are clear. The Sustainable Communities Plan, published by the Labour Government in 2003, sought to address poor-quality architecture and urban development through a new agenda for design quality and a planning system refocused on the public good. Sustainable communities were defined as,

places where people want to live and work, now and in the future. They meet the diverse needs of existing and future residents, are sensitive to their environment, and contribute to a high quality of life. They are safe and inclusive, well planned, built and run, and offer equality of opportunity and good services for all.

(ODPM, 2003)

The question of how best to design our towns and cities grew with the rising profile of the urban designer in the late 1990s. The government established the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) to arbitrate on questions of quality. The experience of the New Towns Programme serves as a test case as to what worked and what did not in design terms, and how issues of delivery and management affect long-term success.

The disconnection between the hope and the reality in both the above statements of intent is a salient warning for the future. Given the decades-long timescale for a town to be designed and built, occupied and grow, and, eventually, undergo incremental change as parts are replaced, the original creators are seldom around to see whether their design ideas remain valid over the long term. But neither can success or failure be anchored in a single point in time. The success of places can rise and fall, perhaps many times over. Economic slumps are followed by reinvigoration. A place that has value, even if just in the assembly of buildings and roads, can always be revisited. Places must continually reinvent themselves as circumstances in the wider world change, and the role they once played changes. As such, the New Towns Programme represents a huge achievement. Compared to the rate of house building at the turn of the millennium, the New Town Development Corporations produced a colossal output.

They may not seem so new any more, but they can still be thought of as young, especially when compared to many of Britain’s towns, some of which have existed for more than two thousand years. They are, at present, moving from youth into adulthood, maturing as places. Part of their absence as a topic for study ...