In order to identify the many different approaches to strategy, we must first establish a theoretical framework with a number of basic concepts and components. That is what this chapter aims to do, by discussing the essence of strategy. What is strategic management about? When we talk about strategy, which themes do we include or leave out? You will notice that occasionally I will mention some of the strategic approaches and schools of thought that we will discuss later on. This is inevitable. In fact, I hope to familiarize you with some of them.

1.1 What do you know about strategy? What do you think about it?

As I mentioned in the preface, each chapter will begin with a number of questions designed to activate your knowledge of and views on strategic management. In the earlier chapters of the book I will place more emphasis on this. I would suggest that you answer the questions below for yourself, preferably on paper, and check them again after you have worked through this chapter to see whether your answers have remained the same. If they have not, why is this?

• In your view, what is the essence of strategy? Think of five words that you associate with strategy.

• When did you last use the terms ‘strategy’ or ‘strategic’ at work, or in another setting? What precisely did you mean by that? Have you recently heard someone else use these words? With the same meaning?

• You are probably a member or employee of an organization. Do you think that the organization has a strategy? Does it matter whether it has a strategy? Who is involved with strategy?

• Do you think that an organization’s strategy must be clear? Should it be clear for the management? For the staff? For potential competitors?

• What do you think of an organization that manifestly deviates from its strategy?

• Is strategic management a matter for top management alone, or should other levels of the hierarchy also be involved? Would you like to be involved? Why, or why not?

• What distinguishes strategic management from ‘normal’ management?

• What is your view of the statement ‘strategy is about the past’?

• Are you already familiar with some existing strategic schools of thought? If so, what are their distinguishing features?

1.2 What are we talking about when we discuss strategy?

Strategy is important

When we talk about strategy, we are talking about important matters. Your reaction may well be ‘of course you would say that, it’s your profession’. No, I mean it literally. Look around you. In many situations, strategy is synonymous with ‘important’. If you want something to be taken seriously, label it as ‘strategic’. Having an action plan is all well and good, but a ‘strategic’ plan really has an impact! A statement about personnel policy is fine, but one about strategic HRM carries real weight! Managers who are involved in formulating the strategy of an organization must be important people. Compare this with how production managers are perceived. Surely production is just as important, even essential? Yet it is unlikely that production managers will be regarded as more important than strategists.

Actually, strategy is important in practice. Decisions are clearly strategic if they are crucial to the development of the organization, have a broad ‘scope’, create ‘added value’, and have consequences for many jobs and activities within the organization. Decisions are also strategic if they are difficult to ‘undo’, for example because they lay claim to considerable resources (human resources, financial resources, machines, buildings, energy) in the longer term. They therefore represent a strategic ‘commitment’ by the organization. They can also serve as a signal to other parties, for example to discourage them from doing the same thing. Such decisions are, therefore, often the motivation for organizing strategic processes or formulating strategic plans. The following are examples of decisions that are clearly strategic:

• Starting a business.

• Investing in a new large location.

• Uniting with your team to oppose a planned reorganization.

• Entering a new market (e.g. the Far East or Eastern Europe).

• Investing in new technologies and innovations in products and production processes.

• Formulating a business plan for a new department.

• Appointing key staff with unique skills.

• Initiating a merger, acquisition or partnership.

Strategies differ in their importance and visibility. To be more precise, the strategy followed in practice is not necessarily the strategy that is set down on paper. Certain difficult decisions are never implemented. Many actions are not the result of formal decisions. That brings us to the first important concept: ‘emergent’ strategy, i.e. strategy that emerges spontaneously. Strategy is often a form of ‘pattern recognition’. As the philosopher Kierkegaard observed, ‘We live life forward but understand it backward’. Ask yourself to what extent your career choices were conscious decisions. Did you really make them logically and rationally?

Sometimes it is also a question of luck or chance. Or did you seize an opportunity that turned out to be just the right one for you? In many cases, you understand the ‘rationality’ (i.e. the pattern) better with hindsight than beforehand. Some strategic literature concentrates on important, ‘strategic’ subjects about which an important decision must be taken: a new direction, a merger, the establishment or closing of branches or departments. But many strategies are the result of a series of smaller actions or decisions that initially seem unimportant. Strategy-forming, then, is more a case of identifying a pattern in our actions after the event. Moreover, it may be that, in the case of an important decision that is expected to generate opposition, tactics are deliberately employed to implement the decision through a series of apparently minor actions. This is known as ‘salami tactics’. The salami is not served whole, but in slices. Salami tactics can be used not only for top-down decisions, but also for bottom-up decisions.

Therefore, the ‘real’ strategy is important. But this is formed not only through ‘important’, well-considered rational decisions. Remember ‘emergent’, spontaneous strategy. I will return to it in Section 1.6.

The air we breathe is free, strategy isn’t

In the past decade we have learned to our cost that linking strategy and importance also has a downside. We often associate ‘strategic’ with ‘costly’ or ‘too costly’. ‘Strategic’ consultancy costs more than ‘normal’ consultancy. When a takeover is labelled as strategic, it often means ‘we have to pay a lot, but … ’ (Kay 1998). Literally one of the most expensive concepts in strategic management literature is the concept of ‘synergy’: the idea that elements interact and their combined effect is greater than the sum of their individual effects. Not infrequently, this is the justification for paying a relatively large sum for a takeover, because the integration of the new organization will supposedly yield even more! A nice idea, but unfortunately that’s usually all it is. In 2002, the merged American Internet and media group AOL Time Warner announced losses of EUR 108 billion, an almost inconceivable amount. To give you some idea, the losses made by a single company within the space of one year were approximately 80 per cent of the Dutch government’s budget in 2005. So remember, next time someone in your organization starts to talk about synergy benefits, don’t let them near the company coffers!

Strangely enough, this shows that some people don’t take strategy very seriously. After all, if strategy is simply a synonym for ‘important’, or even ‘very important’, then there is no need to pursue the subject. The association with ‘too expensive’ (value destruction in economic terms) is possibly even more damaging because in such cases it just means ‘stupid’. It is the exclusive playing field of top management, where there apparently has to be room for the occasional expensive hunting trip. As we know, the true hunter doesn’t rest until he has bagged his quarry. But then he loses interest … It is all well and good if strategy is associated with ‘importance’, but this book will serve little purpose if it means no more than that.

Strategic versus ‘normal’ operational decisions

As I said previously, strategy often arises spontaneously from a pattern of apparently minor decisions. But more deliberate strategies do take the ‘normal’ operational level seriously. Although research has repeatedly shown that, on average, businesses with an explicit strategy perform better than those that do not, the difference is usually not very large (see for example Waalewijn and Segaar 1993). Healthy business operations are just as important. Research conducted by Jim Collins into the few companies that made a successful transition, the results of which were sustained in the long term,1 revealed that a strong strategy was not developed until the process was in its fourth phase, after an ambitious but modest top manager had been appointed and a good management team had been formed, and after the company confronted the ‘hard facts’ (Collins 2001). How can you make good decisions (strategic and otherwise) without an effective management-information system that keeps you informed about the company’s real situation? What are the real costs? Which departments perform best, and why? What really generates our revenues?

That brings us to the next important component of strategy. Strategy is always built on knowledge of the actual strengths and weaknesses of an organization. Does the organization, in its own way, create added value, or not really? The feedback between the strategic and operational levels will therefore be a constant in this book. If the organization’s strategic ‘core competences’ are not anchored in its ‘basic’ processes and skills, then surely we are building on sand? That connection is the essence of strategic learning, however difficult that may be. What activity is the organization involved in, and which opportunities and problems do they create? How can we improve and/or change the way we do things?

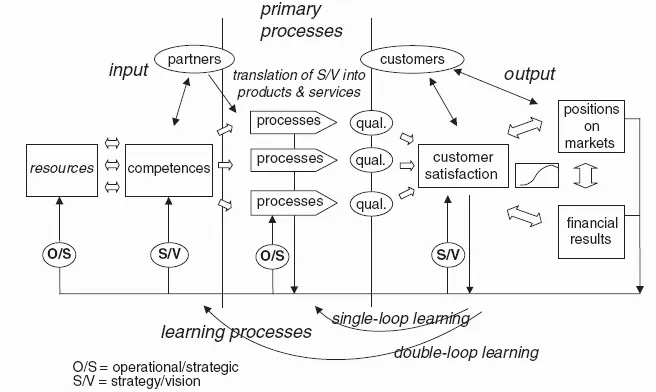

The relationship between strategy and primary processes can involve two forms of feedback and learning: improving what exists and/or creating something completely new. In the literature about learning organizations, a distinction is made between single-loop learning and double-loop learning. When an organization is confronted with a particular problem (or a unique market opportunity), this can be dealt with as effectively as possible using the existing business model. But new ideas may also evolve with regard to dealing with this in a more original and fundamental way, for example by developing new approaches, restructuring the organization, developing new skills, or integrating organizational units. Here we see a relationship between strategy and radical innovation, an increasingly important theme that will be explored later in this book. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1 (based on Jacobs 1999a: 24).

Organizations have material assets (machines, buildings, raw materials and resources) and intangible assets (knowledge and skills) that are used in primary processes. This results in products and services of a certain quality, i.e. added

value. Customers compare the products and services with those of the competitors, and are either satisfied or dissatisfied, which has a direct impact on the result (in terms of profit or market share). The outcome of this and/or other factors triggers new ideas for improvements. Those improvements may involve simple ‘operational’ modifications, which may or may not have a strategic component (O/S in Figure 1.1). But a more fundamental new ‘strategic’ vision may evolve (S/V in the figure) with regard to radically improving the product or service for the customer, and may require new material and immaterial assets.

That brings us to another principle. In contrast to many other people, I believe that strategy is not developed at the beginning of a process, but is always based on experience. Many other books present a sequence other than the one shown in Figure 1.1, beginning with mission–vision–strategy on the left. In my view, however, visions relating to strategy and mission evolve during the process (‘halfway’, as it were), not at the beginning. People who set up a new organization do so on the basis of past experience, as in Figure 1.1, but in a different place.

Provisional conclusions

A couple of matters may have become clea...