![]() I A THEORETICAL BASE

I A THEORETICAL BASE![]()

1 Interdisciplinary Theoretical Foundations for International Public Relations

Robert I. Wakefield

University of Maryland—College Park

The concept of international public relations is rapidly attracting the attention of practitioners and scholars. Since 1990, Public Relations Journal, Communication World, Public Relations Review, and other publications have published dozens of articles about public relations in a global context.1 Interest is increasing in societies like the International Association of Business Communicators and the Public Relations Society of America, which recently emphasized “global public relations” in its national conference and established a section for members specializing in international practice.

This growth in international public relations is phenomenal but also haphazard (Botan, 1992). More and more countries are adapting American or European public relations principles and building a profession along their own cultural lines. But other countries relegate public relations to mere technical tasks, and business leaders in nations like Japan still view the practice as blatant hype, which is problematic in a culture that values understatement and self-effacement (Josephs, 1990).

Public relations often follows multinational organizations as they enter new markets. Many multinationals transfer their own philosophies and personnel into new territories to conduct public relations in their traditional ways. Others localize programs with little or no central coordination (Botan, 1992). Often, organizations turn their entire international communication processes over to public relations or advertising agencies.

WHAT IS INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC RELATIONS?

Ironically, this activity is taking place with little consensus on what the field constitutes. What is practiced in the name of international public relations can vary from simple hosting or promotions to diplomacy and strategic relationship building. To some, as one practitioner lamented, public relations programs “only sound international if you’re on the other side of the ocean” (Anderson, 1989, p. 414). To others, the practice crosses borders but merely as a media relations role or an inexpensive way to support marketing, not public relations, objectives (L. Grunig, 1992).

To date, most articles on international public relations have been anecdotal or descriptive—what Kunczik (1990) viewed as “scientifically non-serious sources” (p. 24). They have handled topics like how a company conducted cross-cultural media relations, or how another handled a crisis in one of its host countries. Many tell how to avoid cultural blunders.

Most of the attempts at scholarly examinations have been country-specific, discussing public relations in a particular country and how it varies from other countries. If conducted well, these studies contribute to the growing body of knowledge about public relations around the world. However, they do not address the need for knowledge about international campaigns that deal with issues and publics across borders (Anderson, 1989; Botan, 1992).

Only a few scholars have tried to define international practice. Wilcox, Ault, and Agee (1992) called it “the planned and organized effort of a company, institution, or government to establish mutually beneficial relations with publics of other nations” (pp. 409–410). Grunig (in press) defined it as “a broad perspective that will allow [practitioners] to work in many countries—or to work collaboratively” with people in many nations (p. 7). Booth (1986) implied that the only true international practitioners are those who “understand how business is done across national borders” and perform in that context (p. 23).

Without consensus on the nature of cross-border public relations, organizations venturing into this environment do so with an unsteady road map to success. Practitioners who do not understand their own field fail to gain the trust of senior managers who desperately need their advice and performance in the complex maze of international relationship building. Worse, they become vulnerable to making, or repeating, costly and embarrassing mistakes.

There is no guarantee that those already in international public relations have adequate international expertise. Farinelli (1990) explained that “public relations has fewer people with international knowledge and experience than any of the other business sectors such as advertising, financial services, and management consulting. We all service the same clients—but public relations has the worst record of all in keeping pace with international changes” (p. 42).

THEORY BUILDING NEEDED FOR THE FIELD

What is needed is a foundation of principles and assumptions that come from scholarly research and theory building on what comprises effective practice in international public relations. Such a base would address normative issues, or what effectiveness ought to look like. These normative principles may be very different from current practices, but they would be based on mounting evidence of what effective practice looks like.

Practitioner Fred Repper (1992) explained that his peers often question whether academicians can “contribute anything of real value” to practitioners. He argued that “scholars . . . are searchers for the reason why, the foundation blocks that are needed so vitally and of such great concern to practitioners” (p. 110). This theory building occurs, as Grunig (1992) affirmed, “piece by piece. . . . It is shaped, revised, and improved to make it more useful for solving problems and directing human behavior” (p. 2).

So let us build the foundation. There are three ways to do this: assemble theories from related disciplines that have thrived internationally and test them in public relations situations; find ways to test theories on public relations in international settings; and build theories from the descriptions about public relations in various countries, using “thick description” (Geertz 1973) to investigate the real meanings behind the activity (a common practice in anthropology). The latter two activities are slowly occurring, as reflected in subsequent chapters of this book. The rest of this chapter concentrates on establishing a framework for using interdisciplinary theories in future research.

With its emphasis on building strategic relationships, public relations encompasses many forms of human behavior. Thus, to build theories for public relations, scholars have drawn from the broader social science disciplines that examine behavior (Pavlik, 1987). Because behaviors are not confined within any national boundary, using theories from other domains is equally appropriate for the study of international public relations. Some disciplines that can provide a foundation for the emerging field are sociology, psychology, political science, comparative management, cultural anthropology, speech ethnography, developmental communication, and mass communication.

MODEL FOR ORGANIZING RESEARCH IN INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC RELATIONS

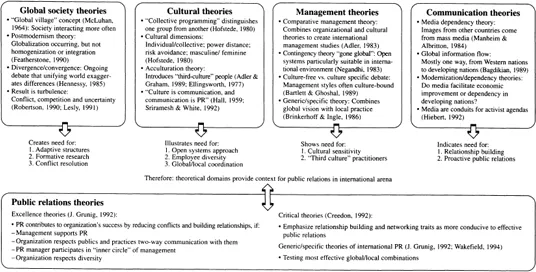

The following pages outline a framework for ordering research in international public relations (see Fig. 1). Theories mentioned here represent the infinite variety that could be relevant to public relations practice across borders. The overall model presented should provide a framework for any path of study that could be pursued for future theory building in the field.

FIG. 1.1. Model for Organizing Research in International Public Relations

The model categorizes interdisciplinary theory into four main bodies: (1) theories of postmodernism and global society drawn from sociology and other disciplines; (2) cultural theories developed largely by anthropologists; (3) comparative management theories derived from international business scholars; and (4) theories on communication. Each category presents implications for international public relations. The base of the model displays representative theories in public relations that address these implications.

Global Society Theories

Scholars in many disciplines have been testing the effects of our increasingly interdependent world on individual societies. These studies often fall within the domain of sociology, but they also have come from such areas as the humanities and international relations (Robertson, 1990).

One theoretical pursuit in this vein is the global village concept espoused by McLuhan (1964). Theories of global modernity originated as early as the late 1700s, when Kant investigated the possibilities of a universal morality (Habermas, 1987). Some sociologists argue that global interdependence now is so complete that scholastic emphasis should shift from local societies to global relationships and issues (Tiryakian, 1986).

Whether or not full globalization has occurred, there is considerable debate about what it means to interacting societies. Scholars typically split into opposing positions of convergence or divergence. Convergence theorists contend that as the world integrates, its societies become increasingly similar. This is reflected in the increased omnipresence of entertainment, fast-food chains, traffic signs, and other symbols of standardization (Hennessy, 1985).

Divergence is a reaction to convergence. When external values invade a culture, they create tension between the forces for change and for maintaining the status quo (Hennessy, 1985). Divergence theory argues that the forces for the status quo will prevent a monolithic world (Featherstone, 1990). Instead, there is a powerful countertrend, a backlash against uniformity, rejection of foreign influences, and assertion of individual culture (Epley, 1992).

The effect of globalization and its resulting tug-of-war is turbulence. While societies are achieving more than ever, their citizens are more dissatisfied (Lesly, 1991). Naisbitt (1994) predicted that governments will continue to break apart, as evidenced by the upheaval of Communism and the growing political turmoil within many countries. Organizations will see an increasing need for small units that can adapt quickly to change. And they will face more hostile and better organized publics (L. Grunig, 1992).

This turbulence creates enormous pressure and opportunity for a unit within organizations that can predict change, identify its sources, and build programs to communicate with those sources to minimize potential damage to the organization. Public relations units, if well trained in environmental scanning and strategic communication, can fill this critical role.

Cultural Theories

All international flights lead through culture; yet, many scholars have affirmed that culture is a slippery concept.2 As Ellingsworth (1977) claimed, “the term culture . . . is plagued with denotative ambiguity and diversity of meaning” (p. 101). Sriramesh and White (1992) added that even “the people of the culture themselves may not be able to verbalize some of their ideologies” (p. 606). Despite this ambiguity, scholars continue to investigate culture and its influence on interactions (Tayeb, 1988).

There are more than 160 scholastic definitions of culture (Negandhi, 1983). Hofstede (1980) called it “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another [and] that influence a human group’s response to its environment” (p. 25). Adler, Doktor, and Redding (1986) identified three determinants of culture: It is shared by all or almost all members of some social group, older members of the group pass it on to younger members, and through morals, laws, or customs, it shapes the group’s behaviors or views of the world.

Even though culture is a nebulous term, its influence on public relations is widely accepted (Verčič, Grunig, & Grunig, 1993). Hall (1959) said, “culture is communication and communication is culture” (p. 191). Communication and public relations also have been viewed as synonymous. Sriramesh and White (1992) explained that “linkages between culture and communication and culture and public relations are parallel because public relations is primarily a communication activity” (p. 609).

Starting with early anthropologists, scholars have identified and studied cultural dimensions. One landmark was Hofstede’s (1980) study of managers in 39 nations that catalogued four different ways to differentiate societies: Self-centered vs. group-centered focus, masculine vs. feminine orientation, power distance between elites and masses in social and work structures, and the extent to which a society embraces or avoids uncertainty. Other scholars offered alternate dimensions, which Adler (1991) summarized as how cultures perceive the individual (basically good vs. basically evil) and the world (trying to dominate or harmonize with nature); activity (achieving vs. being); time (focus on tradition, on short-term results, or on future obligations); and space (whether personal space is public or private).

Sriramesh and White (1992) examined potential relationships between cultural dimensions and the practice of excellent public relations. They hypothesized that cultures displaying low power distance, authoritarianism, and individualism, but higher levels of interpersonal trust would be most likely to develop excellent public relations programs. A question for further study, however, is what influence might public relations practices have on culture?

In Seven Cultures of Capitalism, Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars (1993) sent ominous signals about what cultural differences imply for American organizations. They asserted that economic activity is not based on one form of capitalism, as most Americans presume, but that seven different cultural values influence decisions around the world. The aggregate of dimensions predominant in the United States values the individual and business self-interest, quantification, and short-term results. Human relations and broader societal concerns often are ignored in this worldview. By contrast, cultural values prevalent in most of Asia, Latin America, and Europe place high priority on community and social relationships. They place “all details and all particulars” into intricate patterns of connectedness (p. 109).

Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars (1993) claimed that the American value set is causing its organizations to lose ground in the emerging global marketplace. They argued that in an environment where people, technologies, and issues are constantly changing, “cultures that put the whole before its parts . . . may now have an advantage” (p. 31). To compete, American organizations must embrace what is intrinsic to holistic and communal societies—the human connectedness that increasingly drives global economic activity.

For public relations, this theory suggests a growing need for experts in relationship building, negotiation, and other communal traits. If practitioners supposedly skilled in communication cannot assume these roles, they will miss an opportunity to help guide future economic and social growth.

Perhaps a key to finding qualified international practitioners is acculturation theory from anthropology. This theory addresses what happens at the point of intercultural contact. Specifically, such contact should lead to changes in the previous patterns of individuals, cultures, or both. The nature of these changes depends on such variables as the situation (friendly vs. hostile, use of force, etc.), contact processes (order and type of cultural presentation), and the characteristics of those in contact (Adler & Graham, 1989).

One body of acculturation literature refers to third-culture indivi...