This is a test

- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

LGBT Identity and Online New Media

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

LGBT Identity and Online New Media examines constructions of LGBT identity within new media. The contributors consider the effects, issues, influences, benefits and disadvantages of these new media phenomena with respect to the construction of LGBT identities. A wide range of mainstream and independent new media are analyzed, including MySpace, Facebook, YouTube, gay men's health websites, message boards, and Craigslist ads, among others. This is a pioneering interdisciplinary collection that is essential reading for anyone interested in the intersections of gender, sexuality, and technology.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access LGBT Identity and Online New Media by Christopher Pullen,Margaret Cooper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Active Youth

Chapter 1

The Murder of Lawrence King and LGBT Online Stimulations of Narrative Copresence

Christopher Pullen

Introduction

On February 12, 2008 (in Oxnard, California) a young male teenager Lawrence King (aged 15), who presented an effeminate and sexually ambiguous identity, was murdered in cold blood at school by a fellow classmate, Brandon McInerney (aged 14).1 A few days later in response to the tragedy at E. O. Green Junior High, Ellen DeGeneres, in an emotionally charged state, on her popular network daytime talk show (The Ellen DeGeneres Show,Warner Bros, 2003–, US) told her audience:

Days before [the murder], Larry asked his killer to be his valentine. [pause, studio audience responds with emotional shock “ohhh”]. I don’t want to be political, this is not political, I am not a political person, but this is personal to me. A boy has been killed and a number of lives have been ruined. And somewhere along the line the killer (Brandon) got the message that it’s so threatening and so awful and horrific that Larry would want to be his valentine that killing Larry seemed to be the right thing to do. And when the message out there is so horrible, that to be gay, you can get killed for it, we need to change the message.

[pause, audience applause].

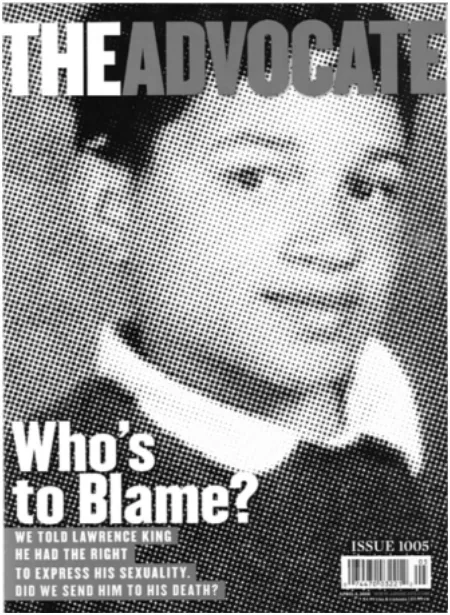

Ellen DeGeneres’ heartfelt and “political” response (despite attestations otherwise), speaking of a need to “change the message,” not only reached large-scale audiences through the television broadcast network, but it also formed a principal point of access and identification on YouTube (2009a), as a video sequence receiving over a million hits.2 The media coverage of Lawrence King’s story, although following in the precedence of the murder of gay youth Matthew Shep-ard (in Wyoming in 1998) and the world wide attention awarded at that time which stimulated anti hate crime legislation,3 received very limited coverage. Only The Advocate (the popular gay and lesbian newspaper) foregrounded his story as a central social concern, devoting their front page cover to this (see Fig-ure 1.1), at the same time questioning the imagined over-confidence of LGBT society which might inappropriately support a youth to express sexual diversity at such an early age, and become vulnerable (see Broverman 2008).

Figure 1.1 Image of Lawrence King appearing on the front cover of the Advocate, April 8, 2008, addressing concerns of culpability in LGBT society encouraging him to experiment with his sexual identity. Image courtesy of The Advocate and LPI Media Inc.

However despite The Advocate’s reflective concern, mainstream media offered very little debate. Nevertheless, vernacular online media commentary, and particularly video web content posted on YouTube, explored Lawrence’s significance as a gay identified youth, and as the victim of a hate crime. Largely these involved intimate responses and took the form of tribute montages, at times in direct response to Lawrence’s murder, and also commenting on Ellen DeGeneres’ notable “political” stance on the event.

A substantial point of reference in the new media content was redressing the lack of mainstream media coverage for the event. This offered moments of self reflexive personal reflection enabled though contemporary media technology, suggesting copresence, “as a sense of being with others” (Zhao 2003) in terms of narrative understanding, revealing empathy and shared experience. Many LGBT new media producers (discussed below), reiterated personal stories of similarly growing up as outsiders at school, establishing Lawrence King as an icon of bravery, in his self confidence of sexual identity. Although new media memorial content produced by his family (Remember Larry 2009), emphasized the loss of a valued family member, and foregrounded an archive of family snapshots revealing Lawrence growing up (which were copied by audiences and used in later news media tributes to him (see below)), direct allusions to a gay identity, or the support of the positive nature of diverse identity, were avoided. Despite this, Lawrence’s reported presentation of a shame free, gender ambiguous identity, and his status as the victim of a hate crime, encouraged new media producers and commentators to construct Lawrence as an inspirational icon of gay youth identity.

This chapter consequently explores the context of Lawrence King’s murder in relation to his status as a victim of a hate crime and his potential construction as a gay teen. At the same time it examines the agency of new media producers concerned for the loss of Lawrence, revealing personal intimations of sharing and narrative copresence. However, as alluded to above, it is important to note that there is a disjuncture between a sympathetic LGBT construction of Lawrence, and his family’s preferred reading of him as disconnected from gay identity.4 Therefore the discussion which follows acknowledges the subjective nature of Lawrence King’s construction as a gay teen as outside his family, potentially appearing in direct contrast to the representation of Matthew Shepard who was murdered in not that dissimilar circumstances (see Loffreda 2000; Pat-terson 2005; Pullen 2007), but who was presented by his family as a beloved gay son. Although Lawrence is reported by peers and teachers to have identified as gay, and potentially may have been transgender in his desire to wear female clothing,5 including a brown pair of stiletto heeled shoes which he bought with a gift card given to him by a gay youth organization (see Setoodeh 2009), as a youth who was troubled he may be read as an unstable identity. Despite this, the narrative of his brave, troubled, and tragic life offered a site of emotive connection. Irrespective of an assured gay (or transgender) identity, his “life story” (Plummer 2001) of transgression, bravery, and ultimate punishment stimulated audiences to reflect.

However, before investigating selected evidence of the new media content in memorial of Lawrence King, produced by Ellen DeGeneres, the Gay Lesbian Straight Education Network (GLSEN), Logo Online, Waymon Hudson,6 Adrian L. Acosta and YouTube producers “live4life1984,” and “Truting” (all discussed below), it is important to consider the context of gay youth at school. This not only offers an insight into the circumstances which may have led to Lawrence’s death, but also it potentially offers resonance and motive in reviewing the stimu-lations of new media producers. In these circumstances, LGBT youth feel ostra-cized and distanced from normative potentials.

Gay Teen Identity: Denial, Rejection, and Symbolic Violence

Ritch Savin-Williams tells us in his groundbreaking book And Then I Became Gay: Young Men’s Stories (1998) that:

Despite the inherent value of romantic relationships, many [gay male] adolescents despair of being given the opportunity to establish anything other than clandestine sexual intimacies with another male.

(p. 160)

Through the presentation of personal narratives, Savin-Williams reveals not only the desire of gay male youths to find romantic partners but also that opportunities for open engagement rarely occur. As outsiders to dominant expressions of romance which reveal the binary dynamic as centered on male and female, same sex potential is denied. When LGBT youths challenge the normative rules of romance, this leaves them vulnerable to the threat posed by heterosexual peers, with “the penalty for crossing the line of ‘normalcy’ [resulting] in emotional and physical pain” (Savin-Williams 1998, p. 161). Clearly Lawrence King’s experience involved this, which is particularly evident in his desire to find a male valen-tine date, and his tragic rejection by Brandon McInerney, in the formation of an ultimate punishment for crossing the boundaries of normalcy.

Significantly LGBT youth need support networks, however as Gerald Unks (1995) obser ves:

[A major] factor contributing to the marginalization of homosexual adolescents is their lack of viable support groups.While virtually all students of any other identifiable group have advocates and support in the high school, homosexual students typically have none.

(p. 7)

This leads not only to a failure for the gay teen to find a positive sense of homosexual identity, but also it reveals the disparity in experience and expectation offered to non-heterosexuals. Although in Lawrence’s case there were some supporters of his attempts to explore his identity: teachers who would reassure him of the everyday nature of diverse identity and orientation (such as assistant principal at E. O Junior High, Joy Epstein (Setoodeh 2009)), and institutions both educational and social (such as an LGBT youth group who were concerned for his welfare), ultimately he was not offered adequate care.

This may be related to the larger issue of the need for social and cultural security for LGBT youth. Generally in schools, there are not adequate social mechanisms designed to protect emerging LGBT citizens.7 Debates within “normative” family and society practically ignore the existence of a non-heterosexual youth, or child.8This is particularly relevant with the issue of growing up at home where, as Caitlin Ryan and Diane Futterman (1998) report:

As [gay and lesbian youth] develop cognitively many … begin to understand the nature of their difference and society’s negative reaction to it. In identifying and learning to manage stigma, lesbian and gay adolescents face additional, highly complex challenges and tasks. Unlike their heterosexual peers, lesbian and gay adolescents are the only social minority who must learn to manage a stigmatized identity without active support and modeling from parents and family.

(p. 9)

Gay and lesbian youth are subject to stigma, and find ways to deal with this often in isolation, without the support of family. Lawrence King’s attempts to deal with his stigma apparently took the form of constructing a “larger than life” identity, performed in a way which might have appeared as entertaining, yet provocative. As Ramin Setoodeh (2009) reports:

Girls [at school] would take photos of [Lawrence] on their camera phones and discuss him with their friends. ..[Furthermore] [d]uring lunch [at school], he’d sidle up to the popular boys’ table and say in a high pitched voice, “Mind if I sit here?” In the locker room, where he was often ridiculed, he got even by telling boys, “You look hot,” while they were changing, according to the mother of a student.

I would argue that such a performed persona, though easily assumed to be calculated to attract attention and to cause entertainment or disruption, reveals much about issues in the management of a stigmatized identity (see Goffman 1986 [originally 1963]; Plummer 1975). LGBT youth as the subject of oppression and rejection, often need to find ways to “make it through the day.” Lawrence King’s apparent over confidence, flamboyance, and imagined effrontery need not have been considered as a problem by teachers and peers, but it may be accepted as an understandable response to social and cultural rejection. For Lawrence this was apparent not only in school, but also in his status as a child cared for by the welfare system, outside of normative ideas of family support.

Generally, LGBT youth are situated on the periphery of normative concerns, and not able to draw benefit from heterosexual networks of support and identification. Furthermore, foregrounding Pierre Bourdieu’s and Jean Claude Passeron’s (2000 [originally 1977]) ideas, they are subject to the “pedagogic action” which is achieved by “pedagogic work” within educational systems, leaving them vulnerable to “symbolic violence.”

Educational discourses which construct the diversity of sexuality as outside the norm (or subject to special attention), reveal the “symbolic violence” of the cultural capital, founded on idealized concepts of legitimacy and authority. Pierre Bourdieu considers that “pedagogic work” contributes to this, in the rejection of difference, as outside hierarchy. As Richard Jenkins (2007 [originally 1992]) tells us further exploring Pierre Bourdieu’s work in this area:

Pedagogic work, and its results, are a substitute for physical constraint and coercion; it is produced out of or by pedagogic authority and subsequently reinforces it. Bourdieu argues that the experience—as a pupil—of pedagogic work is the objective condition which generates the misrecognition of culture as arbitrary and bestows upon it the taken-for-granted quality of naturalness.

(p. 107)

Lawrence’s status as a pupil, who would be subject to the authority and the institution of education which supports normative expectations of gender, displays evidence of “pedagogic work” in the constructio...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Active Youth

- Part II Commodity Networks

- Part III Fan Cultures

- Part IV Body Discourses

- Part V Community Spaces

- Notes on Contributors

- Index