1 Where We Were

Women of the 1950s

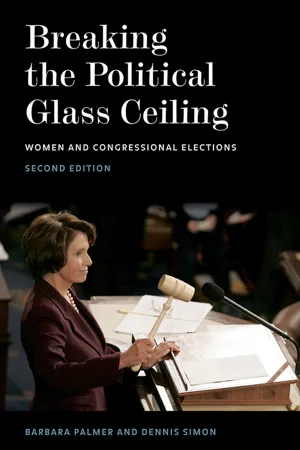

“Today, we have broken the marble ceiling,” announced Representative Nancy Pelosi, after she was sworn in as the new Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives on January 5, 2007. “It is a moment for which we have waited over 200 years. Never losing faith, we waited through the many years of struggle to achieve our rights … Never losing faith, we worked to redeem the promise of America, that all men and women are created equal.”1 After receiving the gavel and becoming the first woman to lead the House, Speaker Pelosi brought all of the children who had attended the ceremony up to the Speaker’s chair, presenting a visual image of power rarely seen in American political history: a woman surrounded by children. Without doubt, her swearing in was a historic moment, but Speaker Pelosi leads a House that is only 16 percent female. The central question that motivates our book is why is the integration of women into Congress taking so long? Are women ever truly going to break the “political glass ceiling”?

A Snapshot: The Women of 1956

In 1956, sixteen women were elected to Congress, fifteen in the House and one in the Senate. The nation had elected President Dwight Eisenhower to a second term of office with 57.4 percent of the popular vote. Eisenhower’s electoral appeal, however, was not sufficient to capture control of Congress. The Democrats enjoyed a 234–201 majority in the House of Representatives and a smaller, 49–47, majority in the Senate.2 The national political agenda was crowded that year. President Eisenhower would address an international crisis triggered in late 1956 by the British-French-Israeli invasion of the Suez Canal. The successful launch of Sputnik by the Soviets added to the anxiety about the ongoing Cold War and sparked a debate about the quality of education in the nation. The debate would ultimately lead to the National Defense Education Act in 1958. In September 1957, the effort to desegregate Central High School would force President Eisenhower to send federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas.

The 85th Congress (1957 session) is noteworthy for two additional reasons. First, the election of 1956 was a high-water mark in the number of women elected to the House. Second, the 85th Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first civil rights legislation passed by Congress since the Reconstruction era. Fourteen of the fifteen women in the House voted for the act, with Representative Iris Blitch (D-GA) casting the lone “nay” vote among them.

Nine of the women in the House were Democrats and six were Republicans. Senator Margaret Chase Smith (ME), the only woman in the Senate, was a Republican. Only one woman, Representative Martha Griffiths (D-MI), was a lawyer. Six were widows initially elected to succeed their deceased husbands. The most senior woman was Republican Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts, a widow first elected in 1925; in 1957, she began serving her seventeenth term. Next in seniority was Republican Frances Bolton of Ohio, a philanthropist and, like Rogers, a widow. Bolton, first elected in 1940, began serving her tenth term. Another widow was West Virginia Democrat Maude Kee, who succeeded her husband, John. When Maude retired in 1964, her son, James, won the election to replace her.3

Many of these women would distinguish themselves as policy leaders in the House. Representative Martha Griffiths (D-MI) was a key force in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and later became known as the “mother of the Equal Rights Amendment.”4 Representative Leonor Sullivan (D-MO) was a cosponsor of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and an early advocate of consumer protection.5 Representative Edith Green (D-OR) “left her mark on nearly every schooling bill enacted during her twenty years on Capitol Hill” and was the author and principle advocate of Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972.6 Representative Gracie Pfost (D-ID), who became known as “Hell’s Belle,” was an opponent of private power companies and fought for federal intervention to manage the project planned for the Hell’s Canyon branch of the Snake River.7

The Rules of the Game

In spite of the tremendous contributions of these women, that only fifteen were elected to the House in 1956 provides a vivid example that women had “a very small share, though a very large stake, in political power.”8 For women, entry into the inner world of politics was largely blocked. Specifically, women who were interested in politics faced numerous barriers, including cultural norms and gender stereotypes that limited their choices, little access to the “pipeline” or the hierarchy of political offices, and the politics of congressional redistricting.

Cultural Norms: A “Man’s Game”

In the 1950s, women were socialized to view politics as a man’s game, a game that was inconsistent with the gender roles to which women were assigned. As Jeane Kirkpatrick explained:

Like men, women gain status for effective, responsible performance of culturally sanctioned roles. Any effort to perform roles assigned by the culture to the opposite sex is likely to result in a loss of status on the sex specific status ladder. The values on which women are expected to concentrate are those of affection, rectitude, well-being; the skills relevant to the pursuit of these values are those associated with nurturing, serving, and pleasing a family and community: homemaking, personal adornment, preparing and serving food, nursing the ill, comforting the downcast, aiding and pleasing a husband, caring for and educating the young. It is assumed furthermore that these activities will consume all a women’s time, that to perform them well is both a full time and a life time job.9

Women attending college in the 1940s, for example, reported being cautioned about appearing too smart and earning top grades, because displays of intelligence endangered their social status on campus. Women were also reminded, typically by their parents and brothers, that pursuing a career would reduce their prospects for marriage and motherhood.10 In 1950, only 23.9 percent of bachelor’s degrees were awarded to women.11 Traditional sex roles were widely accepted by men and women. In 1936, a Gallup Poll asked respondents whether a married woman should work if she had a husband capable of supporting her; 82 percent of the sample said, “No.”12 A similar question appeared in an October 1938 poll; 78 percent disapproved of married women entering the workforce. This included 81 percent of male respondents and 75 percent of female respondents.13 Prior to World War II, the proportion of married women who worked outside the home was 14.7 percent. Labor shortages during the war drew married women in the workforce; by 1944, the proportion increased to 21.7 percent. In 1956, 29.0 percent of married women worked outside the home.14 Working outside the home and pursuing a professional career represented a rejection of tradition, socialization, and conformity.

Also accepted was the norm that politics was the domain of men. A 1945 Gallup Poll reported that a majority of men and women disagreed with the statement that not enough “capable women are holding important jobs” in government.15 In the 1950s, voter turnout among men was ten percentage points higher than among women.16 One survey found that, compared to men, women were less likely to express a sense of involvement in politics; women had a lower sense of political efficacy and personal competence than men.17 The political scientists conducting the survey reported that women who were married often refused to participate in the survey and referred “interviewers to their husbands as being the person in the family who pays attention to politics.”18 Moreover, these cultural norms about women and politics were slow to change. Indeed, as late as 1975, 48 percent of respondents in a survey conducted by the National Opinion Research Center agreed that “most men are better suited emotionally for politics than are most women.”19

Against this cultural backdrop, it comes as no surprise that a “woman entering politics risks the social and psychological penalties so frequently associated with nonconformity. Disdain, internal conflicts, and failure are widely believed to be her likely rewards.”20 Entering the electoral arena was, therefore, an act of political and social courage. The example of Representative Coya Knutson (D-MN) poignantly illustrates that women with political ambitions were often punished. Knutson first ran for the House as a long shot in 1954, defeating a six-term incumbent Republican. During her campaign in the large rural district, she played the accordion and sang songs, in addition to criticizing the Eisenhower administration’s agricultural policy.

In 1958, Knutson was running for her third term. In response to Knutson’s refusal to play along with the Democratic Party in their 1956 presidential endorsements, party leaders approached her husband, Andy, an alcoholic who physically abused her and her adopted son, to help sabotage her reelection campaign. At the prompting of party leaders, Andy wrote a letter to Coya, pleading that she return to Minnesota and give up her career in politics, complaining how their home life had deteriorated since she left for Washington, D.C. He also accused his wife of having an affair with one of her congressional staffers and threatened a $200,000 lawsuit. This infamous “Coya, Come Home” letter gained national media attention, and her Republican opponent ran on the slogan “A Big Man for a Man-Sized Job.” She was defeated by fewer than 1,400 votes by Republican Odin Langin.21 She was the only Democratic incumbent to lose that year.

Serving in political office could also be extremely unpleasant. Women in Congress often had to fight for access and positions, such as committee assignments, that would have rightfully been given to them had they been men.22 For example, in 1949, Representative Reva Bosone, a Democrat from Utah, requested a seat on the House Interior Committee. When she approached Representative Jere Cooper (D-TN), the chair of the Ways and Means Committee who had the final say over assignments, he responded, “Oh, my. Oh, no. She’d be embarrassed because it would be embarrassing to be on the committee and discuss the sex of animals.”23 She shot back and said, “It would be refreshing to hear about animals’ sex relationships compared to the perversions among human beings.”24 When Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) came to Washington, D.C., in 1968, she asked to be assigned to the Committee on Education and Labor. She was a former teacher with extensive experience in education policy while serving in the New York Assembly. Education was extremely important to her poor, black, Brooklyn district. The Democratic Party leadership in Congress, however, assigned her to the Agriculture Committee and the Subcommittee on Forestry and Rural Development. Outraged, she refused the assignment and took her case to Speaker of the House John McCormack (D-MA). He told her she should be a “good soldier,” put her time in on the committee, and wait for a better assignment. Chisholm responded, “All my forty-three years I have been a good soldier.… The time is growing late, and I can’t be a good soldier any longer.”25 She protested her committee assignment on the House floor, stating that “it would be hard to imagine an assignment that is less relevant to my background or to the needs of the predominantly black and Puerto Rican people who elected me,” and was reassigned to the Veterans Affairs Committee.26 It was not her first choice, but Chisholm did note, “There are a lot more veterans in my district than trees.”27 In 1973, Representative Pat Schroeder (D-CO) did receive an assignment on the committee of her choice, Armed Services, but the chair, ...