Chapter 1

The use and nature of public space

This first chapter introduces the concept of public space and seeks to explore the complexity of both public space as a concept, its use and users, and the management of public space as an aspiration and set of activities. The chapter is in three parts. In the first section, the inspirations and objectives underpinning the writing of the book are presented in order to establish the purpose of the book, and equally its limitations. A brief overview of how the book is structured is included here. This is followed by a second section in which public space is deconstructed. This is done in order to draw out and understand the physical and human components of urban public space, in other words, the subjects of management. The third section draws out and discusses the welter of roles and responsibilities for actually managing public space.

The chapter begins the process of unpacking (at least conceptually) the issues that provide the focus for the rest of the book.

The book

Inspirations and objectives

In recent years there has been considerable and growing interest amongst academics worldwide concerning the role of public spaces in urban life. Works emanating from disciplines such as geography, cultural studies, politics, criminology, planning and architecture have tried to define and explore that role, and understand current changes and their consequences. In part, it would seem, this interest was sparked by the almost complete absence of interest in the subject amongst the policy community in many parts of the world in the last decades of the twentieth century, and the impact this disinterest has had.

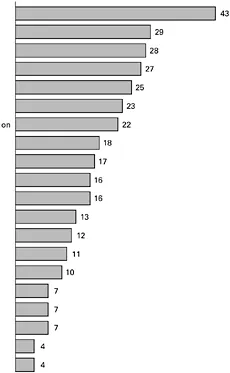

But recent research has demonstrated that people place the quality of their local environment high on the agenda of issues that concern them and most need improving, and often higher than the ‘headline’ public services such as education and health (MORI 2002 – Figure 1.1).

This reflects the fact that people use the street outside their front door, their local neighbourhood and the environment around their workplace on a daily basis, and as a result, the quality of streets, parks and other public spaces affects everyone’s daily life, and directly contributes to their sense of wellbeing.

Yet, in many parts of the world, considerable evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a shared sense of dissatisfaction and pessimism about the state of urban environments, particularly with the quality of everyday public spaces. Explanations for this dissatisfaction have emphasised the poor quality of design that characterises many new public spaces; spaces that are typically dominated by parking, roads infrastructure, introspective buildings, a poor sense of place, and which in different ways, for different groups in society, are often exclusionary.

However, the research upon which this book draws suggests that this is not the whole story. Many contemporary and historic spaces are well designed but have nevertheless experienced decline and neglect. In part this is because the services and investment upon which the continuing quality of those spaces depends have been subject to the same constraints and pressures as public services in general. Changes in the roles of the state and civil society, of government and the governed, shifts in modes of provision of public services, and so forth, have all played a part. These issues touch upon the management of public space, and reflect the impact (positive or negative) of the many different activities that constantly define and redefine the characteristics and quality of that space.

The basis of the book

The book draws upon four empirical research projects as well as a wide body of literature to examine questions of public space management on an international stage. The first project examined the management of everyday urban public spaces in England, the second, the management of green parks and open spaces in eleven cities around the world, the third, three iconic public spaces in New York and London, and the fourth, real users’ perceptions and aspirations for public space in England. The empirical research is set within a context of theoretical debates about public space, its history, contemporary patterns of use and its changing nature in Western society, and about new management approaches that are increasingly being adopted as a response to public space problems in an evolving urban governance scenario.

In undertaking the research over a period of five years, the authors have become increasingly aware that despite the many critiques of public space, its generation and evolution, and despite the voluminous tomes on how to design new public space, relatively little academic literature exists on the subject of its long-term management. In a very real sense, public space management has been a forgotten dimension of the policy discourse, perhaps because so many of the solutions are, on the face of it, quite prosaic: designing with maintenance in mind; regular street cleaning; coordinating management responsibilities; and so forth. Yet, proper management, or the absence of it, can impact in a profound way on the key urban qualities that other policy areas increasingly espouse: connection; free movement; provision of social space; health and safety; public realm vitality; and the economic viability of urban areas.

The four projects were an attempt to understand these issues. In reporting on them, the book addresses one of the big cross-disciplinary debates: how to deal more effectively with the quality of public spaces? In the process it aims to forward a range of practical and sometimes more fundamental solutions to better manage public space.

Defining public space … and the research limitations

Unfortunately, debates about public space are situated within a literature characterised by a host of overlapping and poorly defined terms: liveability, quality of place, quality of life, environmental exclusion/equity, local environmental quality, physical capital, well-being, and even urban design and sustainability. These are all concepts that overlap and which are often used as synonyms, but equally are frequently contrasted, or used as repositories in which almost anything fits (van Kamp et al. 2003: 6; Brook Lyndhurst 2004a).

Broadly, the different concepts owe their origins to different policymaking traditions, each being multi-dimensional and multi-objective. Thus Rybczynski (1986, cited in Moore 2000) describes them as being like an onion:’It appears simple on the outside, but it’s deceptive, for it has many layers. If it is cut apart there are just onion-skins left and the original form has disappeared. If each layer is described separately, we lose sight of the whole’. To add to the complexity, some aspects are clearly subjective, related to the way places are perceived and to how individual memories and meanings attach to and inform perception of particular places. Others are objective, and concerned with the physical and indisputable realities of place (Massam 2002: 145; Myers 1987: 109).

Van Kamp et al. (2003: 11) usefully distinguish between the various concepts by arguing that some are primarily related to the environment, whilst others are primarily related to the person (liveability and quality of place being in the former camp, and quality of life and well-being in the latter). Moreover, some concepts are clearly future-oriented (i.e. sustainability), whilst others are about the here and now (i.e. liveability and environmental equity).

What is clear is that the quality of the physical environment, and therefore physical public space and space as a social milieu, relates centrally to each of these, yet each is also much broader than a concern for public space management. In this regard, defining public space too widely may result in a nebulous concept that is difficult for those charged with its management to address. Conversely, defining the concept too narrowly may exclude important areas for action which, once omitted from policy, may undermine the overall objective of delivering better managed public space.

Debates about the nature and limits of public space will be discussed in some depth later in the book (see in particular Chapters 2 and 3), but for the purposes of defining the limits of this book it is worth presenting, up front, the definition adopted in the various research projects on which Part Two of the book is based. Two definitions are offered. First, an all-encompassing definition of public space that defines the absolute limits of the subject area, and second, the narrower definition, that was adopted as the focus of the empirical research.

A broad definition of public space could be constructed as follows:

Public space (broadly defined) relates to all those parts of the built and natural environment, public and private, internal and external, urban and rural, where the public have free, although not necessarily unrestricted, access. It encompasses: all the streets, squares and other rights of way, whether predominantly in residential, commercial or community/civic uses; the open spaces and parks; the open countryside; the’public/private’ spaces both internal and external where public access is welcomed – if controlled – such as private shopping centres or rail and bus stations; and the interiors of key public and civic buildings such as libraries, churches, or town halls.

This wide definition, encompasses a broad range of contexts that can be considered ‘public’, from the everyday street, to covered shopping centres, to the open countryside. Inevitably the management of these different types of context will vary greatly; not least because:

- the latter two examples are likely to be privately owned and managed, and therefore subject to private property rights, including the right to exclude;

- the shopping centre is internal rather than external and likely to be closed at certain times of the day and night;

- the intensity of activity in the open countryside is likely to be vastly less (at least by people) than in the other two contexts.

For these reasons, a narrower definition of public space would exclude private and internal space, as well as the open countryside. This definition provides the basis for the work:

Public space (narrowly defined) relates to all those parts of the built and natural environment where the public has free access. It encompasses: all the streets, squares and other rights of way, whether predominantly in residential, commercial or community/ civic uses; the open spaces and parks; and the ‘public/private’ spaces where public access is unrestricted (at least during daylight hours). It includes the interfaces with key internal and external and private spaces to which the public normally has free access.

This second definition does not imply that the wider definition is invalid; merely that it is possible to interpret a term such as public space in many different ways. For the purposes of this book, the narrower definition helps to focus attention on the areas where many have argued the real challenge for enhancing public space lies, in the publicly managed, external, urban space. It sets the limits and limitations of this book, which are further limited by a focus on public space in the context of (predominantly) Western, developed countries.

How the book is structured

The structure of the book aims to gradually unpack the range of issues discussed so far, initially by focusing in greater detail on the nature and evolution of public space, and then on its management. To do this, the book is structured in two parts. Part One: Conceptualising public space and its management, constitutes the first four chapters of the book and sets the scene for the empirical research that follows in Part Two. It airs a range of theoretical and practical debates around public space and its management.

In Part One, this first chapter introduces the concept of public space and explores issues surrounding its inherent complexity and the complexity of its management. Chapter 2 then provides a historic context for the discussions that follow by tracing the evolution of public space through history from antiquity to the modern era. Examples of public spaces in London – the historic market place, Georgian residential square and the grand civic square – are contrasted with spaces from New York – the town square, downtown space and the corporate plaza. The historical discussion draws out the changing balance between public and private in the production, use and management of urban space, and key issues for the contemporary management of public space.

The historical review is followed in Chapter 3 by a discussion of contemporary debates and theories concerning public space. The intention here is to draw from a range of literature from different scholarly traditions – cultural geography, urban design, property investment, urban sociology, etc. – to establish the key tensions at the heart of public space discourse. Conflicting definitions of public space will be discussed, and evidence presented about the use and changing nature of contemporary public spaces. The chapter concludes with a new classification of urban space types.

The final chapter in Part One focuses on the management literature, aiming to draw out discussions about the nature of public sector management as an activity and a policy field, and how it relates to public space. A typology of approaches is presented encompassing the paternalistic management of public space by the state, privatised models of public space management, and devolved community-based models. Drawing from the literature, the pros and cons of the different models are articulated, as well as the implications of each for some of the debates discussed in Chapter 3.

Part Two: Investigating public space management presents the four empirical research projects in turn, projects that have systematically addressed the different challenges for public space management identified through the literature discussed in Part One. Together, the projects extend across the national and international stages, and from strategic to local dimensions of public space and its management.

In Chapter 5, a first research project examining the management of everyday urban public spaces in England is introduced. This, the first of two chapters dealing with the project, examines typical practice through interrogating the results of a national survey of local authorities in England and findings from interviews with a range of key stakeholder groups. The intention is to understand the multiple drivers and barriers confronting public space decision-makers in their attempts to improve the quality of public space. Chapter 6 is a second linked chapter which examines a range of innovative practice via case studies identified throu...