![]()

1

Up from Africa

“I like pretty things. Africa scares me.”

(Horniman Museum interviewee)

How do we imagine our African origins? What is the constellation of images, emotions, and ideas that we attribute to our African evolutionary heritage? As this chapter attests, the stereotypical images of the African continent circulating within and outside of museums are not merely visual; they are a dense package of ideas, folklore, ideology, and politics that thrive in cultural memory and our collective imagination.1 By excavating a long genealogy of mythological, religious, and political influences, we can see how “African origins” has come to encompass a complicated array of iconographies that fix Africa and African people in the deep, evolutionary past.

A short history of a long evolutionary tale

Though African people had been figured as pre-humans and proto-humans long before the twentieth century, Africa’s prominence in modern theories of human evolution began with the 1925 discovery of the Taung fossil in South Africa. Challenging popular and scientific predilections to root human origins in either Europe (such as those which motivated the Piltdown European fossil forgery) or Asia (such as those which motivated Henry Fairfield Osborn’s research in Asia), Africa came to dominate the origins map through the diligent work of scientists such as Raymond Dart and Robert Broom in South Africa in the early twentieth century, and later through the work of Mary and Louis Leakey working in Tanzania and Kenya in the mid-twentieth century. Throughout much of the twentieth century, excavation in the East African Rift Valley and Southern Africa was punctuated by a succession of significant fossil finds and generations of celebrated fossil-finders.2

As might be expected, Africa’s designation as the Cradle of Mankind has long met with resistance. In the early twentieth century, African evolutionary origins posed many cumulative ideological hurdles: first, the insult that Europeans evolved from lowly African apes; second, the perhaps greater insult that Europeans evolved from lowly African savages; and, taken together, the overarching insult that God had not in fact created man in his divine, and presumably white, image. To prevail over such psychological affronts, a resolution developed to restore the dignity of Europeans. Divine creation from God was substituted with teleological determinism from African ape to European man. Science was called upon to confirm this conviction in various ways over the years. Sometimes an evolutionary speciation event could be invoked to propel Europeans forward, ahead of their African predecessors and contemporaries (even though this rationale was anything but viable, as humans are undeniably one species). More often, intraspecific events could be invoked to distinguish Europeans from their African roots – for example, the event scientifically known as the European “Great Leap Forward” or “Human Revolution,” a cultural turning point thought to have happened in Europe forty thousand years ago (though now significantly countered by archaeological and paleontological evidence of modern culture in Africa as early as 100,000 years ago, such as in McBrearty and Brooks, 2000).

In the end, Africa’s pre-Darwinian designation as a dark and primitive land simply became overlaid with a new Darwinian distinction – a dark, primitive, and aboriginal land. The West imagined that in Africa humanity could be glimpsed in its most crude and original form. This is a representation that reverberates widely even today from evolution textbooks in the West to eco-tourism on the African continent. Today, then, Africa is often seen by the world outside of it both derogatorily as the “dark continent” and favorably as the “Cradle of Mankind,” a contradiction that has been persistently reconciled through common progressivist logic – Africa serves as the cradle of humanity, while Europe serves as the evolutionary finishing school. This logic has been maintained, and continually reworked, through a long history of representational media.

Africans as mythical European forebears

Comprehensive histories of anthropological race science have been written many times over; it is worthwhile here only to recount in brief the key ideas that have contributed to evolutionary representations of Africa that prevail today.3 Of particular significance are those ideas which culminated in Darwinian anthropology and the Victorian natural history museum in England, an episteme that permeated museums worldwide, particularly those in English-speaking countries, such as the United States, and British colonies, such as Kenya (Bennett, 2004).4

Though much of the most active exploration and imagining of Africa took place in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by Europeans, it is important to remember that the stage was set long before. Through mythological and biblical narratives, many Europeans were already beginning to imagine their forebears. These imagined forebears were often depicted as existing within nature and occasionally alongside monkeys or apes. A significant example is the so-called Plinian races, the wild men of the woods mythologized in folk tales (Stoczkowski, 1997, 259–60; Moser, 1998, 44–52). Most significantly, Herodotus of the fifth century BC wrote of African cave-dwellers, a significant early articulation of the African as cave-man (Marks, 2002, 166). As Moser has pointed out (1998), during antiquity all of the key icons for describing human prehistory were developed: the club, animal skins, nakedness, hairiness, and dark skin. These were all features used to distinguish the civilized from the outsider, barbarian, or Other (although “civilization” was not thought of in those formal terms until later; see Moser, 1998, 169; Jahoda, 1999, 222–5).

A deliberate iconography of origins has existed throughout much of the world at least as long as spiritual and religious ideas. The biblical Adam and Eve, however, were to introduce two new ideologically relentless characters to the origins landscape. As opposed to the European mythological origins tropes emphasizing the bizarre and grotesque, biblical ancestors were an embodiment of human perfection. The contrasts between the wild man and Adam and Eve foreshadow, and were likely influences of, the contrast between images of the African as bestial ancestor and the European as romanticized ancestor.

It is worth emphasizing that the forebears that early Europeans imagined were often depicted classically and medievally as natural and beast-like before the theory of evolution materialized or before distant Others were even contacted. Although “black” came to represent a biological race with culturally specific characteristics, mythologies of difference were in place before knowledge of sub-Saharan African peoples even existed in the West. This suggests the powerful ways folklore and politics fuel the scientific narratives that later came to authorize them.

Quantifying Africans as beasts in the Enlightenment

A whole nation … without the use of speech. This is the case of the Ouran Outangs, that are found in the kingdom of Angola in Africa, and several parts of Asia … they make huts of branches and they carry off Negro girls, whom they make slaves of, and use for both work and pleasure. These facts are related of them by Mr. Buffon in his natural history.

(James Burnet [1773], quoted in Jahoda, 1999, 44)

Although it stems from the “Scala Naturae” of antiquity, the idea of a Great Chain of Being reached its apex of popularity in the eighteenth century and had incomparable impact on Enlightenment representations of cultural difference in general and blackness specifically. This seductive notion depends upon the continuity or interconnectedness of all beings, and upon a linear ranking of those beings from lowest or most primitive to the most human and eventually God-like (see Lovejoy, 1964). The Great Chain of Being also generated much scientific and religious discussion about the relationships between man and apes (the position of Edward Tyson’s “pygmy,” for example, between apes and men; Tyson, 1751), and among men (the position of the races being wrestled with by such scientists as Linnaeus and Blumenbach). The Chain’s steps were fundamentally discrete and linear, making it necessary for scientists working within

the paradigm to resolve the parameters of variation between human races. It was also necessary to resolve issues of monogenism and polygenism and concerns over whether the stages could grade into each other, even evolve into each other, given the right environment and amount of time (Jahoda, 1999, 32).

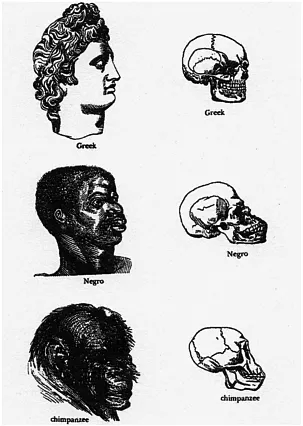

The Great Chain of Being, an ethos as much as a scientific principle, consumed thought on the diversity of the natural world throughout much of the eighteenth century. Bastardized in various creative ways, it had enough power to maintain itself even after the advent of Darwinian evolution, which suggested that species are not static and ranked. The Great Chain of Being could be appropriated in both polygenist and monogenist arguments. For example, monogenists could claim that humans share one origin yet have since differentiated into various steps on the ladder of progress with “Negroes” in distinct phylogenetic proximity to apes. Regardless, scientific ladders of progress validated the inferiority of African people, as in the work of Nott and Gliddon in 1868 which falsely inflated the similarities between blacks and apes (see figure 1.1 and Gould, 1981). These arguments about the natural inferiority of black people became pressing dialogue for scientists and philosophers and particularly in debates between politicians, slaveholders, and abolitionists.

The eighteenth-century Enlightenment, a critical expanse of time in Western thought, was crucial to the construction of ideas about Africa. It is generally held that during this period, reason replaced the mythologies of the previous era. The transformation from mythology to science was not very neat, however; cultural mythologies, particularly those about the people and places occupying distant lands, continued to inform European science. The eighteenth-century enthusiasm for classification is perhaps best reflected in the work of Carl Linnaeus (1707–78), the father of modern biological taxonomy.5 Linnaeus’s enthusiasm for classifying the natural world extended to human variants. Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae of 1735 included a chromatic scale of humanity from black to red and yellow to white. The final tenth edition of Systema Naturae (1758), in a remarkable mixture of the scientifically sound and the imaginary, recognized two species of Homo: Homo sapiens (the diurnal species) and Homo sylvestris/troglodytes (the hairy, nocturnal, mythical hodge-podge species that included apes, albinos, and mutes). Systema Naturae also recognized six subcategories of Homo sapiens: (1) Americans, (2) Europeans, (3) Asians, (4) Africans, (5) Homo ferus, the “Wild Man,” and (6) Homo monstruosus (giants, dwarfs, eunuchs, etc.) (see Jahoda, 1999, 40, 41). The reverberations of Linnaean taxonomies of race were profound, and were significant precursors of racial taxonomies to come (Moser, 1998, 139).

As Europeans began to formally speculate on the nature of reason, humanity, and civilization, they also sought to position themselves on the world map (Brantlinger, 1985; Comaroff and Comaroff, 1991). As European self-consciousness and self-exploration heightened, exploration was enlisted to provide grist for the mill – allowing the creation of a color-calibrated yardstick against which Europeans could judge themselves and others. Africa, then, with its new and strange “darkness” – embodied in its animals, jungles, and people – could be set up as the quintessential Other. Blackness was necessary to legitimize and confirm whiteness, just as evil confirmed good and savagery confirmed civilization.

The Enlightenment was also significant because it triggered the beginning of earnest scientific attempts to quantify human difference, and in particular the affinities between Africans and apes (Jahoda, 1999, xvii).6 It is hard to locate exactly when Africans and apes merged symbolically. Some scholars, most notably Winthrop Jordan (1974), have linked the ideological association between Africans and apes to a simultaneous first contact with each. He writes,

While the coexistence of African people and apes must have profoundly influenced the representative union of the two in the European mind, the union would also gain political significance in the eighteenth century due to the African slave trade. Jahoda argues that it was not the simultaneous first contact with apes and African people...