Chapter 1

Bodies in chains

Wanting to do something, to make a change, to see things as they really are, not as they seem, not as They want you see them? Is it possible? Is it really possible to see radically? Being radical implies some counter-stance to the world as it is, a stance that is active, engaged and committed to bringing about change. But this demands some conception of the world as it is, as it ‘should’ be and where ‘I’ am in it. Being committed and engaged means that any such conceptions of a ‘world’ and an ‘I’ are embodied in material realities where everything is in some way connected as in some sort of either mechanical or organic whole. Can you just ask someone what they do, who they are and this whole shape of connected entities making up ‘reality’ will just pop up? Will a world where people are located in places caught up in some combination of plans, actions and contexts of circumstances begin to be mapped out?

JFS: In order to start can you just sort of give me a sense of your role a’ as you see it in relationship to this area?

Andy: To the project, or to this area?

JFS: To this area generally so I can get some sort of context.

(Transcript extracts, 2006)

It begins with ‘this area’, the defining moment, the setting of boundaries, the framing of context, giving it the sense of a place. This shaping, controlling the field that will be talked about, the field within which things, people and actions and organisations become visible, nameable, addressable. For Andy, once the question of ‘area’ has been settled, responsibilities, identities, purposes, causes, relationships, histories and spheres of action can be named, made known, assigned:

Andy: OK, well, um, I’m responsible for the youth service for X and Y. And I also have a borough wide brief for Millennium Volunteers and for young carers as well. And another part of me remit is uh trainin’ young people and adults in youth work. And that’s how this came about because whereas I was initially asked to get involved in the parenting course it was very much about what we could do for these children of the parents who were having problems.

JFS: Right.

There is a sense of narrative, of a story ongoing, one thing leading to another, purposefulness, being involved in something with people, for people. As he talks, Andy adds detail upon detail, trying to give an accurate nuanced description of ‘how it started’, its ‘origins’, and why it ‘fitted’ the then purpose:

Andy: So that’s how it transpired and it just so happened that we had a course already off the peg that we were doing which was called ‘Youth Work and the Transfer of Local Skills’ which was based between eight and ten weeks – it depends sometimes on the group – but we aim to end it after eight weeks but sometimes it lasts longer which this one just has. And it’s very much about . . . it started out as a senior members course. In other words it was for, originally, for young people who expressed an interest in youth work but were too young. So that was how it started out, and then it turned into this transferable skills course cos we suddenly realised it actually fitted into key skills which is—

There is a sense of luck – ‘it just so happened’ – and of contingency – ‘it depends sometimes on the group’ – and of a discovery of connectedness, rather like the ‘aha’ experience of a sudden realisation that the ‘transferable skills course’ fits with ‘key skills’:

JFS: Key skills, do you mean in relationship?

Andy: Key skills in relationship to like every school and every college and the whole world is doing.

The image is of a totality, a unity of parts, each contributing to and fitting within a whole, a single purpose, a nameable body or mechanical system of action. It is the realisation, the ‘aha’ not of radical difference, but of being a member of a group one hadn’t quite realised before as in Denzin’s (1989) alcoholics who realise that they really are alcoholics. In the social worker’s case, all is subsumed under a directing policy or body (whether this ‘body’ is organic or ‘mechanical’ in nature) of policies within the body politic – he recognises that what he is meant to be doing is fitting in, being the same. And yet, there’s a hint of resistance in the tone of the voice which leaps from every school and college to the ‘whole world’ with its grand universal categories that leads to a further realisation:

JFS: Yeah yeah yeah.

Andy: And the xxxx based citizenship.

JFS: Yeah.

Andy: And all that sort of stuff I won’t bore you with that but we suddenly realised that the course wasn’t so much about young people wanting to become youth workers but young people who needed support in terms of selfesteem you know, stuff like that. So we messed around a bit with the course, took bits of key skills out. So, as you’re probably aware you know with key skills you have to look at sort of literacy and numeracy and stuff like that.

The realisation that a universal concept or general purpose like the ‘citizenship course’ had to be interpreted, interrupted, shaped to be appropriate to particular needs in a particular place and time with specific individuals on a ‘course’, initiates a warping, a twisting of the structure:

JFS: Mmm.

Andy: So we twisted that a bit cos a lot of the young people um we work with are not good with those sort of things and in eight weeks you couldn’t do a great deal in that way but what we thought is well if we do a lot of group work skills at least um they’ll feel a bit more confident. And then maybe we can think of other courses later so that was the sort of aim really. So, it was very much around confidence building, equal opportunities – we obviously have to get in because we’re an equal opportunities service you know – and also uh have fun. So a lot of things we do, sort of group work games to get them to sort of um communicate because a lot of the young people we find who are coming are very quiet, weren’t used to being in a group, weren’t very happy being in a group, so the first four weeks to be honest is very much the emphasis on having fun but obviously learning something from it.

The narrative ends with a resolution of the tension between the whole and the parts. It is a resolution which seems to privilege the needs of the young people. Yet not entirely. What the young people ‘need’ is defined in terms of some image of what they ought to need in order to rectify a lack: they’re ‘not good with those sort of things’, they need ‘confidence’, they’re ‘not used to being in a group’. It is too early to say from these transcript extracts whether the image of the ‘whole’ that is figured here by the social worker is ‘organic’ or ‘mechanistic’. However, there is a sense of dynamism, of pliability, of evolution rather than rigidity and stasis which seems to suggest an organic rather than a mechanistic conception. Whatever is the case, there seems to be a tension between the individual and the whole which, on the face of it, seems resolvable by making the young people fit for social life by constructing a course of activities to help them learn through fun. To become a part, they have to be schooled to fit into the ‘serious order’ of demands, duties and responsibilities. Fun, of course, has the potential to subvert as well as lure. Young people want to have fun, have a laugh (Willis 1977). But the adult of the ‘serious order’ wants fun to be kept within bounds. Already it is tempting to see here the emergence of a ‘universalising case’, something that binds, something that encompasses, within which Andy works in relation to the others who are the actors within ‘the universalising case’. He is a bearer of some universal values that not only allow but also professionally demand that he engages with people at the basic levels of families and the ways people associate with each other in the streets. He ‘incarnates’ those socially or governmentally universalising values, that is, he is the concrete, particular, historical instance through which professional work is undertaken in this particular place with these particular people.

So what are the opportunities for radical research? How does it begin? One beginning is to explore the processes by which complexity is captured by the simplifying categories of normal everyday practices. The opportunity to engage in research radically involves identifying what is at stake for people in engaging in ‘normal’ everyday practices, those practices of ‘fitting in’ and getting others to ‘fit in’ or engaging in strategies in response to their refusal to fit in.

Normal research: what’s at stake?

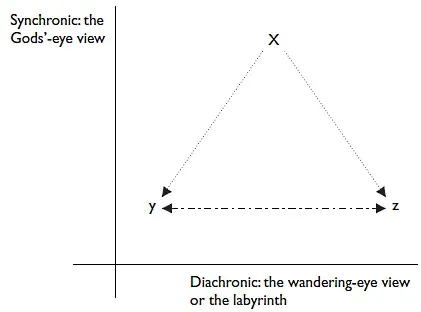

Normal research, rather in the sense that Kuhn (1970) employed his descriptions of normal science, refers to how research is conducted in the context of prevailing, compelling ways of seeing the world as a brute reality, a reality that stands ‘out there’ as something to be encountered, described, understood, mastered. Its features can be seen in any textbook. Its ultimate purpose is to master a view of reality in such a way that all can be explained, all can be subsumed under the general, the universal vision or the covering law of positivistic science (Hempel 1942), with no loose ends, nothing that is not a part of the body of scientific knowledge. It requires some sort of ultimate vantage point as in Figure 1.1, an ‘X’ where all can be surveyed, like looking out from the top-floor windows of the world’s largest most encompassing skyscraper and seeing the scurrying people below, watching their antics, mapping their behaviour, manipulating their comings and goings in what can only seem at street level to be a complex, mystifying labyrinth where everyday events always have the potential for the unexpected, the accidental.

Figure 1.1 The God’s-eye view and the wandering-eye view

The Enlightenment philosophers led the way in contesting the position (‘X’ in Figure 1.1) from which the possession and the legitimation of all knowledge could be claimed. It is a strategy where the radical subjectivity of the individual thinker could suspend all prior thoughts about, beliefs in and dogma concerning the world and how it came to be created. As such, radical subjectivity was in a position to contest the position of God as creator, the one who fashions and sees the ‘whole picture’ – a position that could, and often did, bring the wrath of vested interests to bear on the one making the claims. As in any picture, whether the religious, the mythical or the scientific world views of Enlightenment thinkers, everything has its place, both the shadow and the light. Radical subjectivity, while not yet mastering everything, seeks to master all and subject all to the will whether under Reason, as in Descartes, or under Desire as in Sade. Effectively, one founding myth is substituted by another: Reason or Desire takes the place of God – or they are in complicity with each other. Of course, such challenges in Western cultures can be traced back to other periods of philosophical activity such as Ancient Greece, where Socrates, Plato and Aristotle debated with others about the nature of the world. And around the world, whether in Egypt, India, China or elsewhere, there was the search for knowledge based on human reasoning, observation and skill. It is in these acts that the position of the ‘X’ is made the focus of disagreement, contest, conflict – especially war. It is the place of power and, as such, a highly desirable place to occupy. And from the position of power, all can be commanded through chains of control, reasoning or belief. This is what is at stake for individuals and, in particular, individuals who see themselves as members of a people subjected to the needs, interests, desires of the people.

That ‘knowledge is power’ is a cliché, but, more threateningly, knowledge is political. The control of knowledge and, in particular, the control over what is to count as knowledge is power. For Adorno, O’Connor (2005) argues, every philosophy of knowledge, or epistemology

is determined by a normative commitment to how the world ought to be. Epistemologies thus work within rationalities that defend particular pictures of the subject–object relation, of relations in the world. The description of the subject–object relation is therefore never a neutral report of purely natural responses.

(O’Connor 2005: 1)

Each normative commitment constructs a position ‘X’ from which a god or a godlike being can look down from and map out the entire world according to Reason or Desire as a single fully connected, organic body or structural unity composed of mutually related, functional parts. Of course, there was, and for many still is, only one view concerning how the world ought to be, and that is the one ordained by God, Reason, Science, Tradition or the Leader. There have been, and still are, dangers in being seen to challenge such orthodoxies. Socrates was put to death for having corrupted the morals of the youth; Galileo was imprisoned for the sacrilege of challenging the church’s views on cosmology (1633). The influence of such thinkers as Descartes had personal consequences. A friend of Spinoza, Adriaan Koerbagh ‘was convicted of impiety and sentenced in 1668’, and this friend’s death in prison was probably the reason he (Spinoza) decided to publish one of his major works anonymously (Balibar 1998: 23). In contemporary times, the consequences of challenging orthodoxies can be equally dangerous – either life-threatening, as in the case of Salman Rushdie (1989) for publishing his novel the Satanic Verses, or career-threatening, as in the case of being pro- or anti- some prevailing political view, or being made the object of scorn and ridicule, such as the Picard–Barthes controversy in France (Barthes 1987; Rabaté 2002; Davis 2004) or the more recent diatribes against ‘postmodernists’ as exemplified by Sokal and Bricmont (1997, 1998). While courting controversy may often be a good career move in itself, ‘leaking’ research that damages powerful interests or attempting to undertake research into powerful interests remains a risky enterprise whether for life or career or reputation. Research that radically upsets the status quo is troubling. What it does is assert that freedom to explore the roots of ‘ways of seeing’, ‘ways of thinking’ and their associated social, economic, political and cultural practices is absolute.

The Enlightenment names a philosophical, social, cultural and political project focused upon rationality and freedom challenging the received opinions, beliefs and knowledge about the world as well as having implications for forms of government. Allied to scientific and industrial advance as well as creative experimentation in the arts, it sets apart and establishes the sense of the modern mind and ‘modernity’ from all that had gone before. The march of the enlightenment impulse and modernity has been, it seems, unstoppable. Through it, people came to see the world differently. From the position of the ‘X’ in Figure 1.1, God/Tradition/Faith was ousted by ‘Reason’. The rule of reason could be applied to anything. As applied to education, Locke (1989) considered that reason should rule passion, even to the extent of training children to go to the toilet only at set times in order to bring the bodily functions under the rule of the rational will. It was the mastery of reason over nature, the flesh. Indeed, a German educationalist, Schreber (Schatzman 1973) wrote many influential educational tracts describing in detail the ways in which children should be trained from birth, focusing upon the rational control of behaviour, a precursor, perhaps, to Skinner’s (1953) behaviourism. In such a view, human beings are not constrained to whatever ‘is’, not reduced to being a bundle of instincts, a product solely of ‘nature’, like animals, but are able to construct culture, generate civilisations and have control over their destiny, employing reason in the creation of that freely chosen destiny – a power previously attributable only to the Divine. In short, nature and, in particular, the body, was to be enchained by reason. If people could be educated according to reason, and reason was subject only to the will, then people could be moulded and fashioned to fit any rationally produced vision.

Transitions and revolutions are rarely smooth. Adherents to world views tend not to let go without a struggle. How could rule by reason fit with the traditional forms of society, with the vision of a world created by and ruled by God? What would happen if, through the application of reason, it could be demonstrated that the Earth was not made in six days,1 that it was more than its biblically defined age, that human beings were not made but evolved from the apes, that indeed, the Earth was not the centre of the universe but circled around a sun that itself was lost at the edge of one of millions of galaxies . . . What then?

One solution is to recast God in terms of Reason. If God is perfect, then He is hardly likely to be irrational. Even more usefully, Descartes used the existence of God to solve the problem of other subjectivities. As a rational subject, I can only prove my own existence through the formula, ‘I think, therefore, I am’. I can prove that ‘I am’, but can I found the independent existence of others, the Other (the ‘X’, the whatever it is that’s outside of ‘me’), on ‘me’, my individual ‘ego’? The existence of God as a locus of Absolute Reason transcends all individual rational egos, hence, it could be argued, assuring their existence and the existence of the world and providing a unifying centre for everything. This, of course, is fine if one believes in the existence of God in the first place. But suppose we do. In this case, there is a powerful alliance, hegemony one might say, between religion and reason. But in the process the ways in which people think about themselves and about God undergoes an alteration; that is to say, their identities change. This in itself, of course, is problematic, making a split as it were, between a prior conception and a modern conception. Those who are uncomfortable with such a transformation may want to cling to ‘fundamental’ beliefs, values, ways of thinking and ordering society; preferring to keep the location of authority with the ‘word of God’ as revealed through sacred texts and interpreted by an authorised priesthood; that is, preferring to exclude reason as a basis of action in order to rely on faith in the revealed words of a divine being. Each is radical to the other; each are subversive of the other. As well as the split between a prior revealed truth and truth discovered through reason, there is a split inherent between mind and body, the ideal and the material. If the individual sovereignly decides to doubt all previous knowledge and suspend belief in the everyday realities, then any thing that appears to consciousness is just that: appearance. The solidity of the world is just what appears, the phenomena of consciousness – hence, there is a split between what appears (Kant’s phenomenon) and reality as it is in-itself (Kant’s noumenon). The mind and body split continues, in a sense, the spirit–body split of Christianity – hence paving the way for an accommodation between the two. Where the mind/spirit is set above the body, then there is potential conflict if what the mind/spirit considers to be right does not accord with the passions, the urges, the instincts, the weaknesses of the body. Constructing the chains of discipline, control, surveillance become paramount in order to overcome, free oneself from nature. Given that Descartes and others saw geometry as the paradigmatic method that is both exact and practical in terms of defining and manipulating objects in the world, the implication for research strategies is that the object is split away from the subject, the subject seeking to master the object by isolating it, quantifying it, measuring it in order to manipulate it. This is as true of one’s own body as of the world about. Can the split be resolved in some other way?

Spinoza took a different strategy while adhering to Cartesian principles. It was one that did not involve an essential split as between nature and mind/spirit/God. Rather, the ‘fixed and unchangeable order of nature or the chain of natural events’ is due to God and thus ‘the universal laws of nature, according to which all things exist and are determined, are only another name for the eternal decrees of God, which always involve truth and necessity’ (Spinoza 2004: 44):

Now since the power in nature is identical with the power of God, by which alone all things happen and ar...