![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Mass Media, Aging Americans, and Baby Boomers

The country is growing older. The baby boomer generation—the post-World War II bubble born between 1946 and 1964—is rapidly heading toward the retirement years. The youngest in this group are 40-plus, and face middle age with an eye toward their senior years. The oldest boomers should be planning retirement. All 77 million baby boomers are sure to influence politics, the economy, health care, leisure, and mass media (Alch, 2000). This is particularly true because Americans are living longer, with life expectancy beyond age 77. Other trends also point toward some obvious changes in America and the world:

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that, by 2008, aging baby boomers would inflate the proportion of workers age 45 and older to 40%. This would be a 12% increase in a decade.

- Claritas Research predicted that, by 2007, the number of households headed by 55- to 74-year-olds would grow about 15%, to nearly 31 million. The number of older households with an annual income of $100,000 or more may double by the 2010 Census, to over 8 million.

- Beyond income, the Federal Reserve Board projected that family net worth for wealthy older people may average between $500,000 and $1.5 million over the next several years.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2000 found that older people spend about $72 billion on health care.

- The 2000 Census reported that almost one in four boomers belonged to a racial or ethnic minority—10 million Black, 8 million Hispanic, 3 million Asian, and nearly 6 million multiracial or other U.S. baby boomers.

- Bruskin/Audits and Surveys Worldwide found in 2000 that adults between age 35 and 64 spend an average of 248 minutes a day watching TV, which is 22 minutes more a day, on average, than adults age 18 to 34.

- The median age for the world increased from 23.6 years in 1950 to 26.4 years in 2000. The United Nations Population Division predicted that, by 2050, the world median age would reach 36.8.

Dychtwald (2003a) highlighted the impact of baby boomer wealth, in light of expansive pension earnings and soaring property values, on the future of Medicare and Social Security:

America’s mature men and women have experienced a phenomenal reversal of financial fortune. Society’s poorest segment a few decades ago, they have become its richest. Today’s 50+ men and women earn $2+ trillion in annual income, own 77 percent of all financial assets, represent 66 percent of all stockholders, own 80 percent of all money in savings and loans, purchase nearly half of all new cars, purchase 80 percent of all luxury travel, and account for the purchase of 74 percent of all prescription drugs. (p. 1)

These statistics reflect historic shifts for the country. In the United States, the average age of the population, after decreasing for several decades, has returned to a long-term trend of slowly increasing.

From 1820 to 1950, the U.S. population median age had been growing older. In 1820, when reliable data were first collected, the median age was 16.7, and it rose to 30 as the effects of the baby boom were about to take hold (Gerber, Wolff, Klores, & Brown, 1989). For the next two decades, baby boomers reversed the trend. As Gerber et al. pointed out, “Had it not been for the baby boom, Americans might have turned their attention to their elders sooner than they have” (p. 3).

This is significant because, in the latter half of the 20th century, American media promoted a youth culture, advanced a consumer market, and influenced people around the globe. Perhaps this is about to change: “The new needs of older consumers will ultimately fuel a continuation of the dynamic growth of consumption that has been a vital part of the American economy since World War II” (Gerber et al., 1989, p. 207). Humphreys (2003) argued that “the aging of the population will dramatically alter the typical basket of goods and services . . . purchased by the average American, which will expand markets for some products. In turn, the aging of the population will affect the prospects for many occupations, boosting demand for workers in healthcare, household services, and leisure travel” (p. 1).

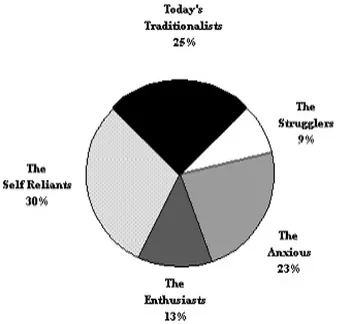

By the time the first boomers reached middle age in the 1990s, the free spirit exhibited by a generation of individuals was leading to a “turmoil” between wants and needs: “On the one hand, they insist on the primacy of the individual—the right to do what they want when they want. On the other hand, the demands made on them by the communities in which they live—their families, their careers, their localities—are growing” (Russell, 1993, p. 10). Increasingly, older boomers will be dealing with issues such as retirement, health care costs, disability, and care giving (AARP, 1998). AARP identified the five segments of the baby boomer generation (Fig. 1.1, Table 1.1): the Strugglers (9%), the Anxious (23%), the Enthusiasts (13%), the Self Reliants (30%), and Today’s Traditionalists (25%).

American mass media seem to be turning their attention to the influential baby boomer generation and their concerns. Passel (2003) noted that, by 2025, the nation will be halfway through the retirement of the baby boomer generation: “This is likely to create a number of problems for the federal government unless some of today’s current leaders are able to come to grips with a problem 10 to 20 years in the future” (p. 1). Demographers

FIG. 1.1. Subgroups of the baby boomer generation. Data from 1998 AARP/Roper Baby Boomer Study (N = 2,001).

TABLE 1.1

AARP Segments of Baby Boomers

| The Stragglers | • | No money in savings |

| Lowest income group | • | Not satisfied with retirement savings amount |

| Disproportionately female | • | Current needs outweigh desire to save for retirement |

| The Anxious | • | Pessimistic about retirement |

| Apprehensive about future | • | Not satisfied with savings for retirement |

| Limited income | • | Concerned about health care coverage |

| Striving to save | | |

| Expect to keep working | | |

| The Enthusiasts | • | Do not plan to work at all during retirement |

| Plenty of money | • | Optimistic about retirement years |

| Eager to retire | • | Cannot wait to retire |

| The Self Reliants | • | Currently investing in range of savings approaches |

| Highest income | • | Confident about retirement income |

| Highest educational levels Aggressively investing | • | Satisfied with amount currently putting away for retirement |

| • | Plan to work part-time mainly for interest or enjoyment sake |

| Today's Traditionalists | • | Confident Social Security will be available |

| Strong sense of confidence | • | Confident Medicare will be available |

| Trust in social programs | • | Plan to work during retirement |

also point out that increasing longevity and delayed retirement are factors that will place economic and political pressures on society.

Since the 1992 presidential campaign, for example, it has been argued that politicians and media have been strongly influenced by the baby boomers (Russell, 1993). In general, baby boomers, or at least their portrayal in media, seemed to be defined as a group that was not like their parents’ generation (Mills, 1987).

Howe and Strauss (2003) predicted a “boomerizing of old age” as the generation moves through its 60s and 70s:

- They will retire later in life, due to economic necessity, forcing businesses to make room for older workers;

- Most will age in place, often turning their large houses into legacy homes for their grown children;

- Those who leave for active adult communities will show an aversion to planned living, and will spread out in places their parents seldom went, such as small towns, college communities, wilderness areas;

- They will continue to assert themselves in the culture, as consumers of products and lifestyles laden with cultural and religious meaning; and

- After initially resisting the idea of growing old, boomers will eventually embrace it, reinvent it, and try to perfect it—less as "senior citizens" than as elder stewards of a great civilization, (p. 1)

These predictions and others, such as whether or not the senior lobby will be influential, raise important social questions. As issues surface, the public, politicians, and media may engage in discussion about the growing impact of an older population. The purpose of this book is to examine how media and aging interact in the United States. How aging in the United States is communicated interpersonally and through media has both theoretical and practical value.

Bridging Communication and Gerontology

A strong interest has developed in the connection between communication and gerontology (Dillon, 2003; Hilt, 1997a; Nussbaum & Coupland, 1995; Nussbaum, Pecchioni, Robinson, & Thompson, 2000; Riggs, 1998; Williams & Nussbaum, 2001). Williams and Ylanne-McEwen (2000) argued, however, that “communication and aging, as well as life-span communication research, remain minority interests within the communication discipline” (p. 4). They studied elderly lifestyles in the new century. Williams and Ylanne-McEwen (2000) contended that “researching communication and aging should not be seen as tantamount to researching decrement, ill health, and disengagement from mainstream life” (p. 7).

There are concerns about how the generations communicate across age boundaries, and media studies also have begun to examine the portrayal of older people and their issues. However, there remains a need to offer a comprehensive examination of mass communication processes, content, and effects. Further, the Internet has created a dramatic need for updating the literature now available. For example, the development of computer-mediated communication as a field of study offers a basis for understanding how older people interact and build online relationships (Barnes, 2003; Jones, 1997). According to Barnes (2003), “Using the Internet to maintain or establish human relationships is a primary motivation for Internet use” (p. 137). In addition, older people seek information via the Internet on issues such as health, leisure, and travel. There is evidence that older people are motivated to use computers to obtain additional information, advice, and input on their decisions. As the baby boomers age, they should be even more likely to use the technology learned in the workplace as a tool to address new life challenges.

There is a need to broadly consider the relation between the fields of communication and gerontology, to focus on mass media, and to conceptualize a structure for interdisciplinary studies. As a starting point, previous research has identified media as one source for negative perceptions about growing older.

Ageism, Stereotypes, and Culture

The study of how media present ageist stereotypes is becoming increasingly important in the communication and gerontology fields. Ageism research began with Butler’s use of the term in 1969 (Butler, 1969, 1995; Palmore, 1999). Ageism has been defined as “a process of systematic stereotyping and discrimination against people because they are old” (Palmore, 1999, p. 4, quoting Butler, 1995, p. 35). Ageism, like racism and sexism, is related to communication because of the social tendency of some to utilize particular frames in discussion of people and issues (Estes, 2001). Age may be treated as a positive or negative concept.

Ageism may be studied from a cultural perspective because “our culture is so permeated with ageism, and we are so conditioned by it, that we are often unaware of it” (Palmore, 1999, p. 86). In media studies, culture has come to be seen as a way of understanding how people live at any given time (Campbell, 2000). Media and culture have been seen as going hand-in-hand in defining our environment: “Societies, like species, need to reproduce to survive, and culture cultivates attitudes and behavior that predispose people to consent to establish ways of thought and conduct, thus integrating individuals into a specific socioeconomic system” (Kellner & Durham, 2001, p. 1).

Holladay (2002) examined memorable media messages about aging. Media are seen as being responsible for cultivating some views of aging:

Through exposure to elderly television and movie characters we may develop conceptions of what later life might hold for aging individuals and ourselves. News reports highlight issues pertaining to members of the older population. Television commercials and print ads heighten our awareness of problems of aging, ranging from cognitive difficulties to impotence to financial insecurity. (p. 681)

However, advertisements may also show older adults being active in promoting the sale of products and services such as “supplements and antiaging creams or the use of security systems and medical devices that promote health, activity, and security” (p. 682). Media, then, serve to reinforce negative and positive stereotypes.

Television, for example, provides cues for the structure of society. Stevenson (1995), drawing from Williams’ earlier work, contended that media transmit culture, as “known meanings and directions” and “common meanings” (Stevenson, 1995, pp. 11–12). For Carey (1992), culture implied “ritual,” “mythology,” and “the creation, representation, and celebration of shared even if illusory beliefs” (p. 43).

Perry (1999) explored “animated gerontophobia” looking for ageism and sexism in children’s films. The research contended that American “society continues to revere youth and deplore aging” (p. 201). The study examined Disney films for evidence of promotion of negative stereotype portrayals. “I identified quite a few aging female villainesses who exhibited many of the negative stereotypes of aging” (p. 202). Six Disney animated films were viewed as important cultural icons. Perry emphasized, “The stereotype of the ‘mean old lady’ needs to be recognized for what it is—a stereotype—and we need to become aware of the insidious influence of stereotypical portrayals in the movies. By continually depicting aging as negative, the me...