eBook - ePub

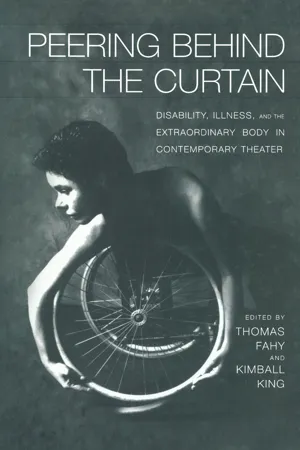

Peering Behind the Curtain

Disability, Illness, and the Extraordinary Body in Contemporary Theatre

This is a test

- 194 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Peering Behind the Curtain

Disability, Illness, and the Extraordinary Body in Contemporary Theatre

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume addresses disability in theater, and features all new work, including critical essays, interviews, personal essays, and an original play. It fills a gap in scholarship while promoting the profile of disability in theater. Peering Behind the Curtain examines the issues surrounding disability in many well-known plays, including Children of a Lesser God, The Elephant Man, 'night Mother, and Wit, as well as an original play by James McDonald.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Peering Behind the Curtain by Kimball King,Tom Fahy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Between Two Worlds: The Emerging Aesthetic of the National Theater of the Deaf

In 1967, the National Theater of the Deaf (NTD) began creating performance works that bridge the deaf and hearing worlds through their combination of American Sign Language (ASL) and speech. In this new theatrical form, both signing and speaking performers are on stage at the same time, and the double language of sign and speech merges image and sound to explore the potential of language as action-in-space. As a result the hearing audiences must learn to listen with their eyes as well as their ears, and because deaf individuals speak visually and kinesthetically in ways unfamiliar to the hearing population, these works challenge the traditional limits of language, poetry, and the use of voice.

Broadly speaking, NTD's work makes deafness visible, and, because the group focuses on classical theater pieces, it achieves this visibility by inserting the deaf into the cultural and theatrical mainstream. NTD's work presents a moment in the discussion of the theory of deafness that “severs the ‘natural’ connection between voice and language” (Bauman, 1996). W. J. T. Mitchell, for example, has noted the potential of sign language poetry to extend the contemporary discussion about the distinctions between textuality and performativity. Mitchell remarks that

The poetry of the deaf stages for us in the most vivid possible form the basic shift in literary understanding that has been occurring before our eyes in the last decade; the movement from a “textual” model (based on a narrowly defined circuit of writing and speech) to a “performance” model, exemplified in the recent work in the semiotics of drama, film, television and performance art and in the interplay of language with the visual or pictorial field. (1989, 14)

Deaf studies theorists Lennard Davis and Dirksen Bauman have also suggested ways—for example, through Davis's notion of the “deafened moment” and Bauman's critique of the relationship between signing and painting—that the examination of deafness can lead to the development of new models for the construction of meaning. NTD's work, in particular, rearticulates the presence of the body, its silences, and the ways in which visuality can speak to us.

This article examines how the sensory modalities involved in the staging practices can facilitate a multisensory, synaesthesiac engagement with performance. Because a language of shape and space is emphasized rather than a language of speech, understanding unfolds through a type of body-to-body listening. In particular, In a Grove, a 1988 NTD production, provides a striking example of how deafness informs NTD's aesthetic, and it articulates ways in which voice, as it crosses between signing and speaking, also refracts the ambiguities involved in listening to another.

In order to hear these multiple voices, the interpretive concept of the third ear1 enables us to track the ambiguous articulations of sound, silence, and image. Through the third ear, we shift our attention from the overt content of the performance to its forms of expression, listening “less to the plot, the narrative, the development of the story… and more to the mode of telling” (Miller 1997, 11). We become more involved in the felt sense of the performance as it unfolds: the silences, the gaps between image and sound, the incongruities between movement and text, dissonant intercessions of noise and gesture, and the positions of the performing bodies that speak to us.

Part of the success of NTD's work lies in its ability to invoke a nonlinguistic, visceral meaning that emerges between performers and audience members, and, through the third ear, we “hear” meaning as it emerges in the performativity of the moment. By disrupting traditional and expected linkages between the normatively audial and visual, the numerous combinations of the performance of sound create new possibilities for understanding, as well as, potentially, for political change.

Homi Bhabha, for example, has written of the power of the performative to insert new realities into social space. This performative dimension occurs in what he calls the space “in-between.” He remarks:

It is in the emergence of the interstices—the overlap and displacement of the domains of difference—that the intersubjective and collective experiences of nationness, community interest, or cultural value are negotiated. How are subjects formed “in-between,” or in excess of the sum of the “parts” of difference (usually intoned as race/class/gender)? (1994, 2)

Bhabha articulates the interval between identity and difference, a central index by which to chart the shifting terrain of contemporary identity politics. The interval, rather than emphasizing an original source for cultural identity, schematizes the way in which identities and cultures are actively produced. Cultural identity, always the result of multiple intersections of meaning, manifests itself through the power of the performative, “emergent” subjectivities.

As new possibilities for multiple voices are created, the very process of hearing requires further examination. Even in its most basic terms “hearing,” as it is embedded within traditional cultural paradigms, is not a perceptual experience of simply registering the presence or absence of sound and concomitant meaning. It also indicates the process of engaging in a cultural and political selectivity. Consequently, a crucial component of hearing the other entails the question of how we hear. Hearing cannot be fully examined without also unpacking the trope of deafness.

This analysis of the intersection of the world of hearing and deafness will be contextualized within the theoretical and historical framework of the National Theater of the Deaf, which is performing an eloquent, newly emerging aesthetic. This aesthetic calls for a sophisticated critical response to how such performance extends deaf culture, examines the trope of deafness, raises the issue of perceptual difference, and suggests ways of reconfiguring what we mean by performance in general.

Overview of NTD's Background

The concept for a professional theater of the deaf began in the late 1950s with Dr. Edna Simon Levine, a psychologist who worked in the area of deafness. She envisioned a professional theatrical venue for the deaf that showcased the use of American Sign Language, mitigating the stigma that was then attached to the use of sign language. Originally, Dr. Levine approached Arthur Penn, who at the time was directing Miracle Worker, and Anne Bancroft, the lead actress, about heading the project to form a company. David Hays, a successful set designer for Broadway productions as well as George Balanchine's ballets, was working with Penn at the time, and he was invited to go along with Penn and Bancroft to Gaulladet College to see the current performance of Our Town. When Penn and Bancroft had to back out of the endeavor because of other commitments, Hays was encouraged to take on the project. In 1967, backed by a $310,000 grant from the Department of Education and a home base in New London, Connecticut, at the Eugene O'Neill Theater, David Hays produced NTD's first performance season.

An initial grant, in 1965, from the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare allowed for the planning stages of the project. Additional funds from the U.S. Office of Education allowed for the development of a summer school program that provided professional training. Hays remarks that

Those were the dark ages. The deaf population desperately needed role models; they had no heroes. Some states would not even license them to teach, because their English wasn't too good. So the government was very practical—it wanted to take people off the dole and turn them into taxpayers. (Quoted in Grandjean 1993, 38)

Despite the fact that the time of the inception of the company was one fraught with social and political problems for the deaf, Hays remained focused on the use of sign language and the creation of the theater as a new form. He has always focused on the “stageworthiness” of ASL:

When you see the words at the same time that you hear them, it gives them an additional meaning. Your eye is caught everywhere by the movement of the language onstage; it's like sculpture in the air. (Quoted in Grandjean 1993,38)

Because Hays approached the challenge of addressing both social and artistic concerns while professionalizing his actors, the company has been highly successful in inserting deaf performers into the cultural mainstream.

Nannette Fabray, a prominent television actress who was hard-of-hearing, helped spearhead publicity during the early stages of the company. In particular, she hosted The Theater of the Deaf, an NBC experiment in TV that was produced in 1967. In describing the challenge of creating a particular scene, she says that “We want to evolve a theater so compressed, so charged that to speak is unnecessary.” She added that “We think we can touch the edges of such total involvement that the body becomes a silent singing instrument of infinite range” (NTD 1967). This vision for NTD argues for the transformative potential of merging sign and speech into a single “charged” form that transfigures the prescribed pathways of communication. Fabray's oxymoron of the “silent singing” of the body illustrates the vision that was driving NTD.

In addition to experimentation with the combined form of sign and speech, Hays also initiated work on new forms of music. NTD is known in particular for their work with the Baschet sculptures, sound structures that create a visual and sonic background for the performances. These new instruments had been created over a fifteen-year period by Francois Baschet and his brother Bernard and were used in the premiere of NTD in 1967.

The instrument sculptures were as tall as twelve feet, and included a twelve-foot gong. The xylophone-like instrument was covered by luminous glass rods and gleaming metals. The musicians played these sculptures with moistened fingers and rubber mallets or bows, and they plucked them like a harp or played them like a piano. The various sounds possible included those reminiscent of African drums, bells, strings, and brass instruments. These instruments provided the means for a sonic and visual staging of music. This approach helped orient the hearing audience, provided vibrations as cues for the deaf performers, extended the possibilities for scene design since the metals could reflect colored lights, and also acted as visual cues for the performers.

Because there were no prior models for the development of theater that used both ASL and English, Hays turned to whatever he sensed would work. One such direction was Japanese theater. In their first season, Yoshio Aoyama directed The Tale of Kasane. While the available description is scant, it is particularly interesting to note that in the Kabuki form the narrators stand to one side while the performers “move” out the action. Rather than being an issue of translation or compensation, the aesthetic form itself—through the separation of sound and image—creates a third, or new, space for the unfolding of the drama.

In addition to Aoyama's Tale of Kasane, the 1967 season also opened with three other works: Gene Lasko directed William Saroyan's Man with the Heart in the Highlands, John Hirsch, Tyger! Tyger! And Other Burnings, and Joe Layton, Gianni Schicci. Although only six people attended the first performance, word spread quickly. Hays attributed the low initial turnout to social misconceptions of deaf people as “freaks.”

The Third Eye, put together and toured in 1972–73, is one of the few works in NTD's repertoire that deals directly with the deaf experience. There were four sections in the work, each one attempting to address deaf/hearing issues from the deaf perspective. One of the sections, “Side Show,” was directed by Open Theatre's Joe Chaikin and NTD's Dorothy Miles. In order to depict normality from the point of view of the deaf, the company portrays the everyday activities of the hearing as freakish. Two hearing creatures, captured for the circus because they hear, are displayed in a cage. The other performers, astonished, gawk and gesticulate at their habits of using a variety of sound-based instruments, such as the telephone, record player, and alarm clock. Further commentary is offered on how the hearing communicate using their mouths rather than their hands. In another section, the performers do a “theater of the ridiculous” version of a familiar children's song. In this section they do a sign-along of “Three Blind Mice” that is reminiscent of a Mitch Miller sing-along.

The Third Eye comments on the difference between perception in a hearing and deaf world without a specific editorializing of the situation. This approach allows the audience to take in the images and absurdities and to make their own connections. At the very least, The Third Eye points out the way in which the hearing population tends to take hearing for granted and all that it implies. Davis notes, for example, that “Disability is a specular moment” (1995, 13), and here we have an inversion of this looking as the deaf—through the third eye—look back at the hearing and position the hearing as the freakish ones.

Shortly after this season, NTD, in 1973, was invited to do a workshop with Peter Brook, who is noted for his experimentation with pushing the boundaries of classical theater. His highly physical approach explored sonic and kinesthetic possibilities, and Brook was particularly interested in developing a universal language for the theater that he pursued in his two most recent works, Ted Hughes's Orghast and Peter Handke's Kasper. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General Editor's Note

- Peering behind the Curtain: An Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Contributors

- Index