eBook - ePub

Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation

The Reproduction of Post-Fordism in Late-Twentieth-Century Architecture

This is a test

- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation

The Reproduction of Post-Fordism in Late-Twentieth-Century Architecture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Studying the relation of architecture to society, this book explains the manner in which the discipline of architecture adjusted itself in order to satisfy new pressures by society. Consequently, it offers an understanding of contemporary conditions and phenomena, ranging from the ubiquity of landmark buildings to the celebrity status of architects. It concerns the period spanning from 1966 to the first years of the current century – a period which saw radical change in economy, politics, and culture and a period in which architecture radically transformed, substituting the alleged dreariness of modernism with spectacle.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation by Tahl Kaminer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architettura & Architettura generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Crisis and withdrawal

The void

‘Today, he who is willing to make architecture speak is forced to rely on materials empty of any and all meaning,’ wrote the architecture historian Manfredo Tafuri in 1974 (1998: 292), expressing a deep disillusion, even despair. This was the era in which architecture found itself engulfed in a crisis, a crisis which appeared to be the result of the disintegration and breakdown of modernism. The crisis was manifested by the realization that ‘modernism had failed’, that the social ambitions of modernism had resulted in disaster. While the exact reasons for this apparent failure were disputed, once the realization spread from the wide public to architects, a shared feeling of disillusionment came to dominate the discourse, triggering soul- searching and a quest for remedy.

The crisis, however, was not restricted to architecture, and encompassed most aspects of society, economy, politics and culture. The cultural critic Robert Hewison described it as

the crisis that afflicts the whole of Western civilisation: how do we maintain and evolve a living and progressive culture when the principal shaping force that has sustained cultural development for most of the twentieth century – that is, the culture of Modernism – appears to have been dissipated?

(1990: 11)

Modernism, in this case, means more than an artistic style: intertwined are the project of Enlightenment and the belief in progress and utopia, ideas that predate the twentieth century, ideas which defi ne modernity itself.

Long before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the radical Left in Europe had lost its trust in the Soviet Union as an alternative model to capitalism. Following the brutal treatment of Hungary and the revelation in 1956 of Stalin’s terror, the radicals of the 1960s railed against ‘the bureaucrats’, targeting the institutions of labour as well as the capitalists.1 The events of Prague Spring in 1968 further eroded the belief in the Soviet Union as an emblem of progress and liberation, instigating a turn to Maoism, a last and desperate revolutionary doctrine. Hewison outlined the growing disillusion:

The price of the break with modernism was the loss of the vision of an improved future for mankind that modernism had helped to frame. After modernism, there was merely a void. This pessimistic view was reinforced by the political pessimism that spread among French intellectuals of the Left in the wake of the failed revolution of 1968.

(1995: 222)

Some of the grievances echoed the suspicions voiced a century earlier by Romantics, such as the fear of the spreading standardization of human existence. This anxiety was increased by commodifi cation pervading all aspects of life and a distrust of a technology that had failed to deliver the utopia promised by earlier visionaries. The impression of a world in which the individual is marginalized as the result of the expansion of the state and the growth of mass media, and the reaction in the form of hyper- individualism, were side- effects of modernity described already in Georg Simmel’s 1905 ‘Metropolis and mental life’; now, it spread to new sectors of society, galvanized by the internationalist, globalized drive of capitalism and the growth of the Western middle class.

The rise of cybernetics in the 1950s and 1960s exhibited an underlying fear of linear time, an uncertainty stemming from progress (Lee 2004). The growth of the middle class brought about a greater demand for privacy at a time in which technological means for surveillance were becoming evermore sophisticated – eavesdropping and bugging devices, CCTV systems, spy satellites. Whereas the conditions of life in traditional society prevented the type of privacy demanded by the middle class, the eavesdropper in the rural village would typically be a relative or neighbour; now, the eavesdropper would be a faceless bureaucrat, a total stranger. The growing anxiety over social control, and in reaction the demand for freedom, is succinctly depicted in Francis Ford Coppola’s paranoid fi lm The Conversation (1974).

Structuralism, made popular by the anthropological work of Claude Lévi- Strauss and the literature criticism and philosophy of Roland Barthes, claimed that non-linguistic systems could be ‘structurally’ studied as languages. Following the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, structuralists analyzed diverse systems using linguistic theories. They identified history-writing as ideological, culturally-determined, and as a myth (Lévi- Strauss 1966; Althusser and Balibar 1970). Consequently, most structuralists preferred analyzing a phenomenon at a specific moment, the present, rather than explaining the manner in which it was historically constituted. In the absence of history, the structures analyzed by scholars appeared evermore independent, fixed, immune and powerful – a-historical, transcendental power- systems over which the human agency has no control. The threat to the individual was only exacerbated by the dark descriptions of power in the work of Michel Foucault. In the world depicted by the French philosopher, human subjects were no longer active agents in control of their destiny, as in humanist thought, but mere cogs in an oppressive system and structure, a system which was beyond the individual’s ability to steer or affect (Berman 1983).

The structuralists were not alone in dismantling the traditional underpinnings of historical materialism. Jean- François Lyotard, the ‘prophet’ of postmodernism, distanced himself from Leftist critique, which he viewed as merely negative and non-constructive; ‘we have no horizon of emancipation’, he declared (cited in Bürger, C. 1992: 75), proceeding to outline individual transgression and spontaneity as an ‘affirmative’ means of resistance. Lyotards’s Dionysian nihilism, which rejected all ‘meta-narratives’ and embraced desire in its demand for individual freedom, was primarily directed against Reason, and focused on counter-cultures and ‘little narratives’ as the locus of a positive alternative. Inevitably, the Frenchman left no space for organized, orchestrated, planned, or collective resistance. Lyotards’s nihilism was related to the advent of post- structuralism in the 1970s, encouraging a shift towards relativism, eroding the vitality of ideologies by presenting them as ungrounded, undermining their truth value. While primarily aimed at dominant ideologies, Jacques Derrida’s Deconstruction undermined all ideologies. At the end of the day, contrary to the intentions of Derrida, Deconstruction did more damage to the opposition ideologies: once all positions were undermined, exposed as ungrounded, the desire to replace an ungrounded dominant ideology with an ungrounded oppositional ideology faded. Furthermore, once Deconstruction was exported to the United States, and particularly to Yale University, Paul de Man and his colleagues diluted Deconstruction of its radical political imperatives, applying it as a nihilistic linguistic game, a vacuous, self-indulgent academic practice.

The loss of the utopian horizon, the rejection of history, the doubts regarding technology and the threat to individualism meant that the idea of progress was increasingly questioned and finally rejected as a myth. These doubts were raised even by archetypal progressive modernist thinkers such as Theodor Adorno, who noted that ‘[n]o universal history leads from savagery to humanitarianism, but there is one leading from the slingshot to the megaton bomb’ (2001: 3). The questioning of utopia and progress were, in many ways, a sign of a more mature society, more aware of self-created myths and delusions, freeing itself from subordination to the illusions of grand narratives. It also meant a growing awareness of the monstrosities created by modernity, the injustices and horrors of the Soviet gulags and the shanty towns of the third world.

The transformations described above were expressed in an ideological crisis, a crisis of consciousness. The ideological crisis erupting in the 1970s was a refl ection of greater social changes that had been evolving for some time as a result of economic developments that mutated capitalism, namely, the passage into post- Fordism. This passage meant a general shift of economic paradigm: the industrialist interest in production was replaced by the growing importance of consumption. It meant the rise of the service sector, of immaterial commodities such as information, and the decreasing significance of traditional industries and tangible products. The shift placed increasing importance on advertising, branding, lifestyle, perception and image: a worldview which emphasized everything that was beyond the material properties of the product and aspects of production, which centred its attention on society’s superstructure rather than base (Jameson 2009; Baudrillard 1983, 2005). The actual product – its utility, its quality – was superseded by interest in the image of the product, in the desire it could evoke in consumers. The interests of economy and society moved decisively into an intangible world.

Classical capitalist economics ascribed a ‘truth’ value to the market, seen as an objective arbiter of exchange value according to supply and demand; it presumed the consumer is an objective, rational agent, spending capital rationally, according to needs (Bell and Kristol 1981). The Nobel Prize laureate economist Daniel Kahneman proved otherwise, using behaviourist psychology to study and illustrate the irrationality of consumption (Kahneman et al. 1982). Entrepreneurs and chief executives, however, did not need to wait for scientifi c proof. Advertising, born already in the nineteenth century (Williams 2005), had grown to monstrous proportions in the post- war years thanks to the expansion of mass media, expressing the implicit understanding that consumption depends on perception and illusion rather than an objective, utilitarian ‘truth’ or reality.

The intangibility of the late capitalist economy evolved directly from the abstractness of money, an abstraction that encouraged perceiving unequal products as the same – the result of identical exchange values. Credit cards and debit cards introduced a new level of abstraction, with their value dependent on the bank account and credit and, consequently, their exchange-value becoming ‘invisible’, represented by the brand of card. The economic changes created a situation in which a significant section of the labour force was ill-adapted to the evolving order; labourers in traditional industries found themselves facing mass unemployment as their labour was no longer required in an economy based on services and increasingly on information technology industry.

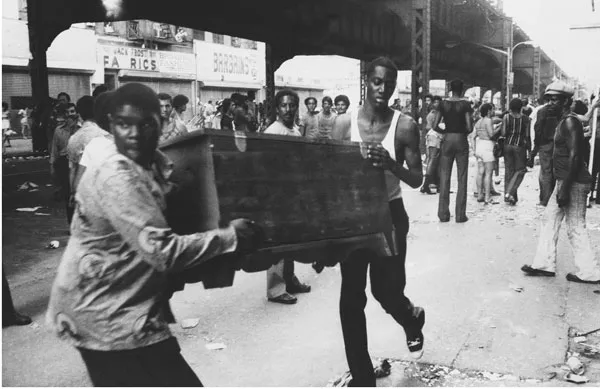

In the 1970s, a decade of social and economic turbulence, the West suffered from recessions, inflation, unemployment, social strife, labour protests and strikes. This was the decade of the economic meltdown triggered by the oil crisis, of factories reducing the working week due to the energy shortage, of New York City facing bankruptcy, of the Summer of Sam (Figure 1.1),2 of punk, of the Winter of Discontent,3 of the collapse of inner cities, of widespread riots and of urban guerrillas such as the Red Brigade. In France, for example, during the years 1971–5 there were, on average, four million strike days per year, compared to less than half a million in 1992 (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005). In 1973, Wall Street shrunk by 15 per cent, with another 12 per cent of its employees becoming redundant in the following year (Sorkin, A. R. 2008). The 1970s was the decade in which the social landscape was adapting to the new economic order, and to do so, it needed to lay waste to the previous order – the Keynesian welfare state model in Europe and Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States. The social unrest that began as an attempt to further the achievements of the working class became focused, increasingly, on preventing the unwarranted changes, on preserving the economic model that had brought prosperity to the West in the post- war years. A large segment of the population felt directly and profoundly threatened by the changes. The trade unions, which brought about increased wages and job security during the previous decades, were now seen as government collaborators by the ultra- Left; consequently, a proliferation of ‘wild cat’ strikes circumvented the traditional trade unions and weakened them. The growing unemployment, riots and strikes brought about a general dissatisfaction, which was increasingly directed at the status-quo, and thus, gradually, instead of preventing the changes, politically enabled them.

1.1 Chaos in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighbourhood during the 1977 New York City blackout.

Copyright AP/ Reporters.

This section of the book will identify the epicentre of the crisis in the transformation of political economy that began in the 1970s and necessitated the restructuring of society. It will delineate the manner in which the crisis evolved in architecture and in society; the transformation of the motivations, aims and ideals of society – the transformation of ‘the spirit’ of society – will be outlined as the engine behind the mounting pressure on architecture, as the reason for the growing disenchantment with the promise of modernism and modernity. The condition of crisis exposes the relation of architecture to society, demonstrating the manner in which certain changes affect all aspects of life, ranging from economy to architecture, from politics to culture, in an attempt to ‘streamline’ society, to dissolve contradictions and erase remnants of the previous order. The crisis of architecture encouraged soul-searching and self-critique; it caused widespread anxiety and uncertainty within the discipline. In reaction to this aporia, architecture withdrew into itself, into a form of regressive resistance or escapism, succeeding in identifying many of the discipline’s ‘ailments’ but lacking a remedy, often ignoring the wider social transformation and centring its attention on its own production. This withdrawal, in turn, was enabled by the dominance of the ideal in architecture, a dominance that is determined by the distance separating drawing and building, and by the schism of subject and object.

Economic and social crisis

Jürgen Habermas has noted that ‘society does not plunge into crisis when, and only when, its members so identify the situation’ (2005: 4). Whereas a consciousness of crisis, a social crisis and an economic crisis are often related, and severe states of crisis affect all three categories, the three can also take place separately, in isolation. Habermas has pointed out that ‘when members of a society experience structural alterations as critical for continued existence and feel their social identity threatened can we speak of crises. [. . .] Crises states assume the form of a disintegration of social institutions’ (2005: 3). A partial crisis is manifested primarily economically and is related to the business cycle of economic upturns and downturns, a characteristic of capitalist economy; a wider crisis, in contrast, is related to the transformation of society’s organization, social relations, and the political- economic steering of society. Habermas has elaborated the latter form of crisis:

Crisis occurrences owe their objectivity to the fact that they issue from unresolved steering problems. Identity crises are connected with steering problems. Although the subjects are not generally conscious of them, these steering problems create secondary problems that do affect consciousness in a specific way – precisely in such a way as to endanger social integration.

(2005: 4)

A decline in productivity followed by crisis is an inevitable occurrence in capitalist economies (Habermas 2005; Craig- Roberts and Stephenson 1973). While the free market strives for equilibrium, such a state can only be temporary; equilibrium between supply and demand is unachievable due to the separation of production from consumption. There will always be, in the conditions of market capitalism, a disparity between the number of commodities being produced and the demand for the commodities: the producer has no means of accurately predicting future consumption. While in one industry an unnecessary amount of labour exists, another is short of labour. The oscillation between equilibrium and disequilibrium is an essential characteristic of the free market and the cause of repetitive partial crises. Consequently, capitalist economy constantly suffers from small, partial crises, which are limited to a single producer or industry. As capital tends to be invested and re- invested in an evermore diverse and complex manner, the consequences of a partial crisis can easily spread within the system, affecting industries that had been highly profitable. Thus, capitalism produces crises as a means of rectifying the system once growth slows down, a ‘shock therapy’ of sorts that redistributes labour according to the needs of production and consumption. The growth of the economy and of capital investment leads to greater complexity and counter- dependence across the system, increasing the economy’s vulnerability to crises (Mandel 1975; Craig- Roberts and Stephenson 1973).

Such crises were related to laissez-faire capitalist economy in nineteenth-century Europe and United States. However, the post- war situation was different. Already in the 1930s, following and in reaction to the 1929 crash and the Great Depression, the United States implemented new policies in accordance with Roosevelt’s N...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part One: Crisis and withdrawal

- Part Two: Autonomy and the resuscitation of the discipline

- Part Three: The Real

- Notes

- Bibliography