![]()

1

Introduction

ETHICS LANDSCAPE

In virtually all areas of society ethical issues are mushrooming. Professionals in the health field grapple with ethical questions about transplants, abortion, birth control, life-support systems, informed consent, human genetics, patient privacy, malpractice suits, and high costs of insurance and care in general. Ethical concerns about oil spills, nuclear power accidents, defense weaponry, disposal of industrial waste, acid rain, lead and asbestos poisoning, and ecological balance confront those in science, technology, and industry. People in the political arena deal with ethical questions about homelessness, unemployment, welfare reform, Social Security, foreign policy decisions, law enforcement practices, electioneering costs, racial and gender discrimination, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) activities, drugs, crime, immigration control, and lobbying activities. The legal profession is accused of unethical practices like charging exhorbitant fees, stimulating an unhealthy litigious spirit, engaging in questionable plea-bargaining practices, and advertising improperly. The business and corporate world is challenged on lack of truth in advertising, selling unsafe products, committing white collar crimes, practicing insider trading, being involved in savings and loan scandals, and giving unbridled allegiance to the profit motive. In mass communications an overwhelming concern with profit produces demeaning entertainment, sensationalism, dramatic investigative reporting, manipulation of photography, invasion of privacy, little interest in truth telling, suspect allocation of resources, and questionable editorial decisions. “Never in the history of our profession have editors and reporters been more aware of the need for ethical behavior and the ethical treatment of stories,” wrote McMasters (1996, p. 17). Academia is plagued by accusations of questionable research procedures, an interest in furthering personal research rather than honoring good teaching, engaging in excessive outside consulting, pandering to contemporary trends, and bowing to business demands. Irresponsible individualism and unbridled greed seem to be on the increase, not only in the United States but also in former Communist countries like Russia. These widespread conditions have stimulated an intense interest in ethics, and an indignant citizenry is demanding a more ethical standard of behavior.

Legislative ethics committees in state and national government have been making serious efforts to increase ethical standards. In February 1996 Congress passed and President Clinton signed the historic, sweeping Communications Decency Act, which includes requiring the V-chip in television sets, and thus permits parents to block out objectionable programs. But in June 1996, a panel of three federal judges in Philadelphia castigated the Act and “declared the internet a medium of historic importance, a profoundly democratic channel for communication that should be nurtured, not stifled” (Quittner, 1996, p. 56). Strident and reckless rhetoric, many feel, have helped to create an atmosphere conducive to violent acts, like the assassination of the Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995. In January 1996, a group of moderates in the U.S. House of Representatives formulated a bipartisan resolution calling for a more civil discourse in their proceedings, and the British House of Commons has recently done the same. Some corporations and even cities have set up ethical practices boards to monitor the ethical atmosphere and to investigate specific complaints. Communities have set up a special “values week”, hospitals have created ethics committees, and car dealers have held special workshops on increasing ethical behavior in selling practices. Programs on ethics have appeared on television, and magazines and newspapers have allocated space to discussing ethics. Books and articles have been devoted to discussions of ethics in various professions, and a few journals about ethics in specific professions have appeared in the last decade.

College mission statements now include an emphasis on ethics and values, and commencement addresses not infrequently dwell on the importance of ethical commitment. New courses in applied ethics, are appearing throughout academica, for instance, in schools of law, medicine, dentistry, engineering, business, and social work. By the mid-1990s, 90% of the business schools offered courses in business ethics, with a total of about 500 such courses (Hausman, 1995). Departments of philosophy, where ethics have traditionally been studied, are being asked to create courses in applied ethics for engineers, lawyers, and doctors. Departments of political science, mass communication, and others have constructed courses in ethics relevant to their areas of study. Newly endowed chairs in ethics have been created, some on an interdisciplinary arrangement. Applicants for graduate school have been including an ethical dimension in their program projections. Job openings in colleges and universities have begun listing an interest in ethics as a desired qualification.

Ethics centers, independent or attached to a college or university, have been created and are increasingly active. A number of such centers are listed in Appendix A, and another list appears in the Spring 1995 issue of Ethically Speaking, the semiannual publication of the Association for Practical and Professional Ethics. The programs of many ethics centers include awarding research grants for studies in ethics. These centers and other sponsoring agencies have increasingly set up conferences, seminars, and workshops about ethics in the fields of medicine, engineering, technology, business, law, education, and other professions.

The field of speech communication shares this strong interest in ethics. Speech communication departments are creating undergraduate and graduate courses in ethics, and are including sections on ethics in other courses. More Master’s theses and Doctoral dissertations on communication ethics are appearing. International, national, regional, and state speech communication associations are increasing their activities on ethical issues. For example, in 1985 the Speech Communication Association created a Commission on Communication Ethics that, among other projects, holds a biennial conference on communication ethics, sponsored in part by Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. Publications in speech communication now deal with ethics. New textbooks or new editions of popular textbooks, especially in public speaking but also in discussion, interpersonal, organizational and intercultural communication, are including new chapters or sections on ethics. Ethics in speech communication, in academia, and in the larger society will be in the forefront of concerns as we enter the 21st century.

Through the centuries, ethics has been a central emphasis of the field of rhetoric. For example, Aristotle insisted that a rhetorician’s personal character, or ethos, was crucial to effectiveness, and Quintillian asserted that a good orator is a “good man speaking well”. Hugh Blair, the 19th century British rhetorical theorist, wrote: “In order to be a truly eloquent or persuasive speaker, nothing is more necessary than to be a virtuous man” (Golden & Corbett, 1968, p. 458). In the mid-20th century, Thonssen and Baird (1948) concluded in their classic work, Speech Criticism: “The cultivation of a sense of responsibility for the uttered statement is a crying imperative for public speakers today—just as it was yesterday and will be tomorrow” (p. 470). Today people in high and low places are using their natural and carefully honed communication skills in demeaning ways for dehumanizing and often cruel ends.

Those of us in speech communication must live up to D. K. Smith’s (1979) observation: “I think it is good that we have never ceased to engage our students in confronting the eternal ambiguities linking effective speech practice to ethical speech practice” (p. 103). We have excessively focused on achieving effectiveness—on convincing audiences, converting skeptics, winning the debates—without balancing these aims with the ethical commitment. We must blend proficiency and ethics, skills and compassion. As the Association of Communication Administrators stated in their 1995 definition of their profession: “The field of communication focuses on how people use messages to generate meanings within and across various contexts, cultures, channels, and media. The field promotes the effective and ethical (italics added) practice of human communication.”

KEY TERMS

I define ethics as the moral responsibility to choose, intentionally and voluntarily, oughtness in values like rightness, goodness, truthfulness, justice, and virtue, which may, in a communicative transaction, significantly affect ourselves and others. Ethics refers to theory, to abstract universal principles and their sources, whereas morals implies practicing those principles of applied ethics, our culture-bound modes of conduct.

The ethical dimension affects decision making when two or more options are viable and can be freely chosen. Pike (1966) put it well: “There is no point in analyzing what men [sic] ought to do if they are powerless to choose what they will do” (p. 1). Choice must be intentional and voluntary: The communicator can then be evaluated by relevant values. Unintentional misrepresentation of facts marks an intellectual, not a moral, failing. When choice is by chance unintentional, a communicator’s ethical judgment is meaningless. A communicator’s intention is a prime consideration in ethical judgment. When a communicator is coerced to engage in an involuntary communicative transaction, normal ethical standards hardly apply. Furthermore, we should “view intentionality as existing in varying degrees and, as we interact, we may engage in multiple intentions” (Sharkey, 1992, p. 271).

Oughtness is at the heart of ethics, and thus ethics are inevitably involved with prescriptiveness. Prescriptive ethics, guided by the highest ideals, measure acts accordingly: descriptive ethics emphasize that as ideals are usually unattainable, we must focus on what “is” rather than what ought to be, on what ethical guidelines people actually use. Although the descriptive approach has helped to stimulate ethical analysis, we must ultimately grapple with oughtness. In fact, descriptive ethics are insufficient. Their blind allegiance to the status quo rests on several factors: chance (what mores have been established and why); power (who exerted the influence to establish the norms—bullies, people of wealth, an occupying military force); chronology (who first established the norms); majoritarianism (quantity does not necessarily imply quality); and tradition (“it has always been done that way”). What is continues to operate; the status quo does not change for the better unless human agents intervene; and such intervention arises from prescriptive oughtness.

Oughtness does battle over values. We struggle to understand right and wrong, good and bad, true and false, just and unjust, virtuous and corrupt. In dealing with these ends, we assume that we seek the right, the good, the true, the just, and the virtuous rather than their opposites. Himmelfarb (1995) wrote about the shift in vocabulary and mind-set from virtues to values. Virtues which flowered in the Victorian era, were fixed and clear, she contended, whereas values are vague. Although I do not share her interpretation and her anxiety, her point deserves consideration. Values, abstract conceptions that people consider desirable, do not usually act in isolation from one another; for several intertwined values often affect decision making, with one or more taking precedence at any moment. Often two or more “good” values clash. For example, peace is sometimes willfully violated by social activists seeking justice in the political and social arenas. Freedom of expression may conflict with social responsibility; liberty, with safety. The legitimate journalistic goal of getting a good story may collide with values of privacy, honesty, and compassion. This clash of values creates issues. Values in conflict are like natural laws in conflict. For example, icycles are temperature’s triumph over gravity, but gravity still exists even though it does not take precedence at that moment.

The Josephson Institute of Ethics, in Marina del Ray, California, has generated what the Institute calls core values, six “pillars of character”: respect, responsibility, trustworthiness, caring, justice and fairness, and civic virtue and citizenship. Searching for core values on the international scene, Rushworth Kidder and his Institute for Global Ethics, in Camden, Maine, has arrived at eight: love, truthfulness, fairness, freedom, unity, tolerance, responsibility, and respect for life. Defining each value and distinguishing between almost synonymous terms and concepts is difficult. Fairness or example, is sometimes used interchangeably with equality, but the former is a qualitative conception and the latter a quantitative one. Parents may justify giving different sized weekly allowances to their 12-year-old and their 6-year-old, because of the children’s varying needs, household chores, and ability to handle money responsibly. Traffic lights are adjusted to give more time to a major thoroughfare than to minor cross streets with few cars—unequal but fair and reasonable for traffic control. Giving equal television time to every political party on television means giving each one not only the same number of minutes but also the same quality of broadcast time.

This book deals with verbal, nonverbal, written, and pictorial communicative transactions, direct or mediated via an electronic means, with the circular dynamic of both senders and receivers as potentially active participants. It covers the entire landscape of interpersonal communication, public speaking, small group communication, mass communication, and intercultural communication. This provides us the opportunity to bring together the divergent courses in our field, to be a cohering force, to create an umbrella under which we see the interrelatedness of the many areas of our profession. The organizing framework of this book is the fundamental paradigm of the communicative process: the ethical concerns revolving around the communicator, the message, the mediums (the plural mediums is used here rather than the often used Latin form media, for the latter is so embedded in our lexicon to mean electronic mass media), the receivers and the situations. I focus on the ethical tensions within the familiar question: “Who said what through what medium to whom in what context with what effect?”

Of central concern is the effect of the communicative act. What is the effect on immediate and long-range audiences? Centuries ago, Augustine (1949) warned rhetoricians racing after superficial superiority to look deeply into the potential harm of their remarks:

In quest of the fame of eloquence, a man standing before a human judge, surrounded by a human throng, declaiming against his enemy with fiercest hatred, will take heed most watchfully, lest, by an error of the tongue, he murder the word “human being”; but takes no heed, lest, through the fury of his spirit, he murder the real human being, (p. 22)

Are people with whom we are intimately identified—family, relatives, friends, fellow employees, club members, religious affiliations—honored or ashamed by our communicative efforts? How are we ourselves affected by our communicative acts?

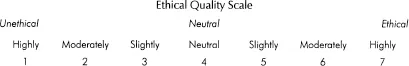

ETHICAL QUALITY (EQ) SCALE1

Throughout this book I emphasize the need to think in terms of the degree of ethical quality, not in terms of simplistically labeling words or deeds as either ethical or unethical, automatically eliciting a yes or no response. Setting up only two options, one totally good and one totally bad, we must instead ask, “How ethical is it?” This question elicits a statement of degree, a degree of ethical quality (EQ). On a seven-point Ethical Quality Scale, a communicative act can be highly ethical (7), moderately ethical (6), slightly ethical (5), neutral (4), slightly unethical (3), moderately unethical (2), or highly unethical (1).

By refining our judgments, we can continually probe the possible variables, nuances, and consequences that may alter our evaluation. For example, lying to a thief may warrant an EQ 7, because of the dangers involved: lying in other circumstances may call for an EQ 1 or 2 rating. We thus can appreciate the complex milieu of most communicative transactions. By avoiding hasty categorical judgments and pronouncing the case closed, we can continue to analyze and then communicate our specific evaluation. The EQ Scale stimulates us to note positive as well as negative instances. The latter usually capture our full attention; we are drawn to ethics only when a grievous negative instance occurs. The EQ Scale also helps us to see that we are generating opportunities for communicative acts that enrich the lives of many. In the familiar Latin terms, a 5 is cum laude (with praise), a 6 is magna cum laude (with great praise), and a 7 is summa cum laude (with highest praise). Likewise, a 3 is with condemnation, a 2 with great condemnation, and a 1 with greatest condemnation.

As Hausman (1995—1996) has written, we must dwell on those gray areas in the middle as well as on the two extremes. Most of the action in a football game takes place between the two 10-yard lines, yet we tend to highlight the action inside the 10-yard lines. We need to pay more attention to mid-field play, where our ordinary communicative experiences fall. Case studies all too often conjure up major dramatic goal line episodes far removed from the small but significant decision-making tasks of everyday life. Dorff and Newman (1995) put it this way: “We misrepresent the moral life when we focus only on dramatic choices and overlook the many attitudes and values that express themselves in everyday life and which shape our sense of ourselves” (p. 247).

The EQ Scale gives us the opportunity and encouragement to voice our displeasure (at a 2 or 3 rating), without calling something unethical when that is the only terminology available. Using a scale gives a sense of freedom as well as precision within evaluative processes.

CAUSES OF LOW ETHICAL QUALITY BEHAVIOR

Most people acknowledge that we all have moral shortcomings, but simply viewing evil as caused by evil people is obviously incomplete and inadequate. A host of mixed motives, many of which are good, usually operate. Acting on narrow loyalties may be one motive. Secretaries may lie out of loyalty to a boss, and be disloyal at the same time to the broader society. Members of...