![]()

1

INTRODUCTION TO SINGLE-CASE RESEARCH

An overview

In this chapter, we will:

• introduce the concept of single-case research designs in sport and exercise;

• describe different single-case research designs in sport and exercise;

• describe how single-case research designs can contribute to research and practice in sport and exercise.

Introduction

The purpose of research is to increase knowledge (Clark-Carter 2009). This book presents one type of research design for sport and exercise scientists and practitioners to fulfil that objective: single-case research designs. Single-case research designs can complement and extend a sport and exercise literature that relies generally on traditional group designs. In this book, single-case research designs are discussed primarily from a psychological perspective, which is in keeping with most literature on single-case research designs and our background as sport and exercise psychologists. However, the principles and guidelines outlined can be applied to other domains in sport and exercise, such as coaching, biomechanics, physiology and nutrition.

To begin this book, this chapter explains what we mean by ‘single-case research designs’, introduces the different types of designs and provides examples of these designs in understanding human behaviour generally and sport and exercise specifically. We finish by outlining when single-case research designs can be useful in sport and exercise contexts.

What is single-case research?

In single-case research, data are typically collected from one participant. The researcher is interested in exploring what changes occur in response to the manipulation of one or more variables. For example, a tennis coach may be interested in the influence of positive feedback on her player’s confidence levels, or a psychologist may be interested in the influence of a psychological skills package comprising imagery and positive self-talk on the anxiety levels of a junior sprinter. There are variations of this typical model. For example, rather than collecting data from a single participant, the focus may be on investigating outcomes at a group level. The single case in this example would be an identifiable group such as a sports team or exercise class. To illustrate, an exercise leader may choose to explore whether or not offering incentives to attend an exercise class increases attendance. Sometimes a multiple-baseline design is used (see Chapter 6) in which data from more than one participant (usually about three or four) are reported separately. If the participants demonstrate similar changes in response to the variable or variables manipulated (i.e., each case looks similar) it strengthens the conclusions that the researchers can draw from the data because of the replication of effects. Although there are variations in the type of design that can be employed, a single-case research design is usually about what happens to one person. It is this reliance on data from single individuals that makes single-case research problematic for some scientists and practitioners – especially those trained in the logic of group comparisons. Yet in this book, we aim to demonstrate that single-case research designs can make a significant contribution to sport and exercise literature. More precisely, over the coming chapters we intend to explain why, and show how, single-case research designs can be effectively, rigorously and scientifically used in sport and exercise settings. In doing so, we seek to extend the original contributions to this area in the 1980s and 1990s, made most noticeably by Bryan (1987), Hrycaiko and Martin (1996), Jones (1996), Mace (1990) and Smith (1988).

Before we describe what single-case research actually is, we will briefly discuss case studies. Case studies are often mistaken for single-case research; however, in a case study observations are made under uncontrolled and unsystematic conditions (Brossart, Meythaler, Parker, McNamara and Elliot 2008; Goode and Hatt 1952). Away from the academic literature, many people in sport and exercise settings intuitively use a case-study approach. For example, in an effort to increase his knowledge of elite teams’ training methods, the football manager, Roy Keane, went to New Zealand in the summer of 2008 to observe how the All Blacks rugby team prepared for competitive games. Case studies also abound in exercise settings with numerous examples in the popular media and in the advertising literature of gymnasia providing case studies of individuals who have benefited from increasing their exercise activity. This shows that many people believe that case studies can enlighten and motivate. In short, the informal study of individuals and organizations as case studies may be used to illustrate understanding and development in sport and exercise.

Case studies of individuals are also well represented in the scientific literature. Indeed, they have stimulated current understanding of human behaviour and functioning. For example, many psychology students are aware of the consequences of a horrific accident suffered by a man named Phineas Gage in 1848 (see Macmillan 2000). He was working as a construction foreman when an accidental explosion propelled an iron rod under his left cheekbone, through his frontal cortex and out through the top of his skull. The subsequent change in Phineas Gage’s personality, particularly his impaired social skills, illustrated the important role that the frontal cortex played in social activity. The case study describes an event and outcome but does not enable the experimenter to control any of the variables involved. An interesting example of a case study in sport and exercise comes from the work of Vealey and Walter (1994), who interviewed the Olympic archer, Darrell Pace, about his approach to competition. This case study about a successful Olympic athlete yielded some valuable information on important aspects such as the type of training regimes that are most effective, what psychological strategies might help performance in competition and how these psychological aspects might be developed. Although interesting, it is a descriptive case study and it is impossible to determine with certainty which aspects were instrumental in helping Darrell Pace achieve Olympic success.

Case studies can also describe an intervention carried out to produce a desired change. An example of a case study in sport is the work of Mace, Eastman and Carroll (1987) with an Olympic gymnast. Figure 1.1 reveals the main essence of the study.

Figure 1.1 Stress inoculation and gymnastics.

The case study reported by Mace et al. (1987) is appealing because it outlines how to apply a psychological intervention to help a high-level athlete. Of particular interest is the way in which the intervention is structured, comprising an education phase (session 1), a skill acquisition phase (sessions 2–6) and an application phase (sessions 7–12). This illustrates how psychological skills can be introduced, acquired and transferred to the competitive arena. In that sense it is a useful paper because it illustrates how psychological skills training can be delivered in an applied setting. However, as with all studies, it has certain limitations. For example, it is not possible to determine unequivocally from the case study if it was the intervention that resulted in the positive change and, if so, what the nature of that change was. Also, no measures of anxiety were taken. There was no formal comparison of competition performance scores from before and after the intervention to resolve whether the techniques employed actually produced a meaningful change. In short, Mace et al.’s (1987) study lacks objective pre- and post-intervention data and that makes it difficult to accurately determine the effect of the intervention.

To summarize, case studies are often mistaken for single-case research but they lack the control and rigour that enable definite conclusions to be drawn from the data. It is not that case studies cannot illustrate, educate, enlighten, interest or motivate. They can. But because they lack control and rigour, the conclusions that they generate are limited, and by themselves they cannot be considered to satisfy the highest standards of scientific research. However, as we shall now explain, it is possible to conduct research with a single participant and that is the focus of the remainder of the book.

Single-case research designs

As we have just explained, case studies are descriptive methods and lack sufficient experimental control to exclude the threats to internal and external validity (see explanations of these terms in Chapter 9). In that sense, a case study cannot be considered a research design; however, it is possible to bring rigour to research with one participant. For example, Ebbinghaus, a German psychologist, provided some of the earliest studies of memory (Ebbinghaus 1964). He explored the factors influencing the recall of nonsense syllables (e.g., ‘juz’, ‘gof’). Although Ebbinghaus manipulated the variables of interest (e.g., amount of nonsense syllables), and rigorously recorded the outcome (e.g., time taken to learn the syllables), the data were collected from one participant – himself. Clearly, Ebbinghaus’ seminal research yielded fundamental principles of memory that are still, in general, accepted today (Morgan and Morgan 2001). In research with a single participant (or group) it is possible to have similar rigour to that used in experimental designs in which a control group is compared on performance with experimental group(s). These more rigorous studies are called single-case research and it is these designs that are the focus of this book. Using a single-case research design, a researcher can control the independent variable(s) or introduce an intervention and examine the influence on the dependent variable(s). Throughout the book we often refer to dependent variables as target variables. In this section we describe the different types of design in single-case research.

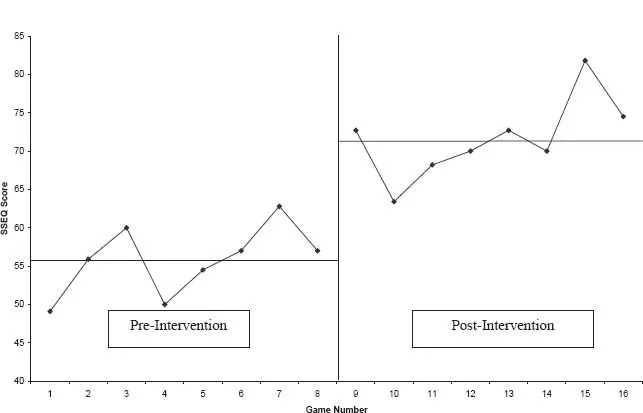

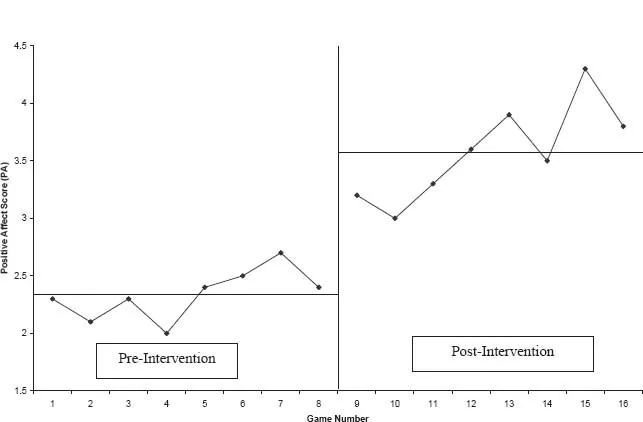

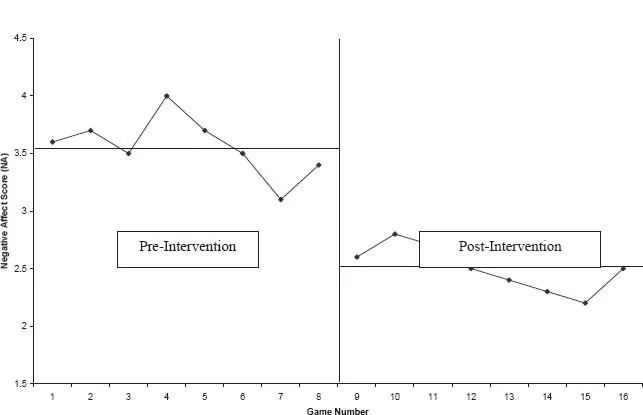

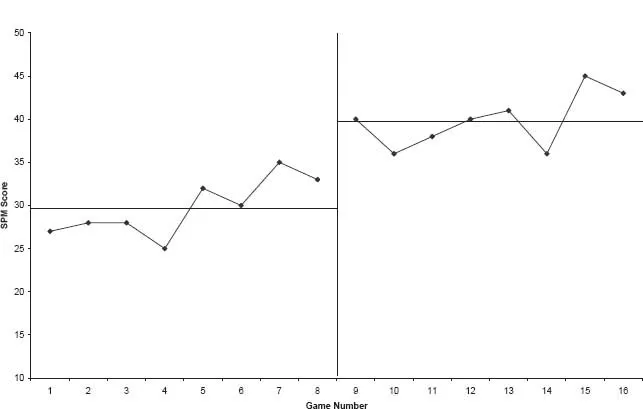

To illustrate how a single-case research design can be applied in sport and exercise, an athlete’s target variable (e.g., behaviour, or psychological response) is measured repeatedly, and a baseline established, so that trends and changes in the data can be examined as the treatment is introduced, and even possibly withdrawn (Kratochwill, Mott and Dodson 1984). In effect, the participant acts as his or her own control by comparing changes following the intervention to the baseline (control) phase. One common design is an A–B design in which the variable of interest (e.g., performance, or a psychological construct such as anxiety) is recorded during a baseline phase (A) and compared with that recorded after the intervention (B). For example, a psychologist interested in applying a relaxation technique to help a young athlete cope with the pressure of competition may record her anxiety over a series of eight competitions before administering the intervention and monitoring anxiety levels in a subsequent eight competitions. An example of an A–B design is shown in Figures 1.2–1.6 in which Barker and Jones (2008) reported the effects of a hypnosis intervention to enhance mood and self-efficacy in a professional soccer player.

Figure 1.2 Hypnosis and soccer performance.

Figure 1.3 Pre- and post-intervention soccer self-efficacy. Reprinted with permission from J. B. Barker and M. V. Jones (2008) The effects of hypnosis on self-efficacy, affect, and soccer performance: A case study. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 2, 127–147.

Figure 1.4 Pre- and post-intervention positive affect scores. Reprinted with permission from J. B. Barker and M. V. Jones (2008) The effects of hypnosis on self-efficacy, affect, and soccer performance: A case study. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 2, 127–147.

Figure 1.5 Psychometric data collected from a professional soccer player. Reprinted with permission from J. B. Barker and M. V. Jones (2008) The effects of hypnosis on self-efficacy, affect, and soccer performance: A case study. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 2, 127–147.

Figure 1.6 Pre- and post-intervention soccer performance scores. Reprinted with permission from J. B. Barker and M. V. Jones (2008) The effects of hypnosis on self-efficacy, affect, and soccer performance: A case study. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 2, 127–147.

One potential problem with an A–B design is that it is possible that any observed differences may be a consequence of maturation (i.e., normal development) and, hence, may not be caused by the intervention used. Designs in which the intervention is withdrawn (A–B–A; see Chapter 5) or withdrawn and then re-introduced (A–B–A–B; see Chapter 5) can also be used. If the variable of interest changes in line with the introduction or withdrawal of the intervention then it is possible to have confidence that the changes occurred because of the intervention. For example, a rugby coach may be interested in exploring if providing individualized feedback on a player’s performance after each game increases game involvement. The coach hypothesizes that individual feedback will reduce the tendency for this player to ‘coast’ during games and increase the tendency to maintain effort. Game involvement may be assessed by a pre-determined set of criteria (e.g., number of passes, tackles, line breaks). Baseline performance could be monitored for a number of games, the individual feedback introduced for a period, then removed and then re-introduced. If game involvement increases when the individual feedback is introduced, reduces when it is removed and increases when it is re-introduced then individual feedback would appear to be associated with increased game involvement.

With some interventions (e.g., those in which the participant is asked to use a particular psychological technique or learn a particular behaviour), this may not always be possible. To illustrate, it may be difficult following a cognitive restructuring intervention (i.e., the participant is trained systematically to think about some aspect of his or her game in a more constructive manner), such as in a case in which a field hockey player addresses her aggressive behaviour towards umpires. After the intervention, the player may recognize that, because umpires do not change decisions, complaining is futile. So it would be difficult in this circumstance to ask the hockey player to return her thought processes to the way they were before the intervention and behave accordingly. Also, if an intervention is successful, an athlete may not want to stop using a strategy that is helping him or her perform well. For example, an athlete may not want to stop using a relaxation strategy that he or she perceives is useful. Nevertheless, there are illustrations of intervention withdrawal being achieved. For example, Heyman (1987) managed to get an amateur boxer to cease using a hypnotic intervention that was successful in silencing the sound of the crowd. The boxer found the sound of the crowd anxiety-inducing and detrimental to performance. The boxer was very pleased with the success of the intervention but agreed not to use the intervention in one fight only before it was re-introduced.

In single-case research, by using an A–B–A–B design it is possible to demonstrate the replicability of effects (Kratochwill et al. 1984). In an A–B–A–B design, this ...