This is a test

- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In The Creative Therapist, Bradford Keeney makes the case that "creativity is the most essential aspect of vibrant, meaningful, and successful therapy." No matter what therapeutic orientation one practices, it must be awakened by creativity in order for the session to come alive. This book presents a theoretical framework that provides an understanding of how to go outside habituated ways of therapy in order to bring forth new and innovative possibilities. A basic structure for creative therapy, based on the outline of a three-part theatrical play, is alsoset forth. With these frameworks, practical guidelines detail how to initiate and implement creative contributions to any therapeutic situation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Creative Therapist by Bradford Keeney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Bringing it Forth

Chapter 1

Theatre of Creative Transformation

Setting Up the Three-Act Play

All schools of therapy are vulnerable to getting lost in a session (which is not always a bad thing!) because they lack a compass or a map—they have no practical way of keeping track of their location and movement. Clinicians sometimes don’t know whether a session has even moved one step forward. Similarly, they may be unaware when it has backed up and become more entrenched in a stuck place or gone down a side road where everyone is completely lost in a different form of entangled discourse. How can we keep track of where we are in the flow of a session?

Most of the arts have a practical means of scoring the movement of performance. For example, a musical score tracks the melodic line (along with harmony and rhythm), whereas dance notation symbolically lays out the dance moves. With a musical score, a musician is aware of where he or she is in the song—where the notes of the melody are in relation to the beginning and end, whether it is the verse or chorus, and so forth. A clinician without a means of scoring his or her journey is like a musician without a song (whether internalized or written), or a dancer without choreography, or a filmmaker without a screenplay. It’s probably even worse—it’s more like an explorer without a compass and map.

Of course there are times when performers spontaneously make up a song, dance, or play without following a score. But at any time during the flow of the creation, or afterward, they know how to map the movement—the progression of notes, steps, and themes they went through. Therapists generally don’t know how to do this. They typically haven’t even asked the question. They just make theoretical generalizations about what they think happened on an abstract level. This is probably because the profession has lost awareness of its being primarily a performing art. It therefore has grown accustomed to giving less importance to what is actually taking place in a session—its live performance—than to indulging in the hermeneutics of interpreting it.

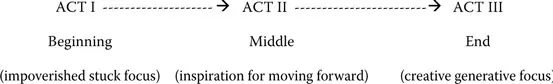

The elementary three-act structure of a theatrical play or movie screenplay provides a starting point for helping us know where we are in a clinical session. All performance, including the clinical theatre of therapy, can be scored so as to notate the progression through a beginning, middle, and end. Keep in mind that the end may be another beginning or the middle (or start) may be experienced as some kind of end. The movement does not have to be linear. A session might turn out to be a big U-turn, or a running in circles, or even a progressive spiral, to mention a few possible patterns.

Syd Field (1979), the author of Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, outlines the pattern that most screenplays follow. They usually work with a three-act outline that marks the temporal flow of a performance in terms of beginning, middle, and end acts. The transitions between acts are called plot points, those moments or events that shift the plot in a new direction. As an elementary form for the staging of theatre and film, the basic structure for the performance of creative therapy also can be based on the outline of the three-part play. It gives us a practical way to keep track of where we are in a session and whether we are stuck or have moved in any direction.

Again, all performed plays benefit from having a means of knowing whether they are in the beginning, middle, or end. This also applies to the producer of a therapeutic play. If you end a session and haven’t moved anywhere, you need to be aware that you got stuck in the opening act. If you find yourself in the middle, it’s good to know that you moved forward but that there was no achievement of resolution or closure. Therapists of all schools and orientations can learn from the lessons of screenwriting how to know where they are in the unfolding of a therapeutic plot, storyline, or dramatic enactment.

Creative therapy aims to bring forth a session that is well formed and whole. That is, every time you meet with clients, you aim to have a beginning, middle, and end. Each session should hold the progression of all three acts, that is, be a whole session. This approach used to be called single session therapy. Let’s now call it whole therapy. To illustrate:

In the beginning, people usually (but not always) complain. They are stuck in an onslaught of complaints. The more they and others think, talk, or do anything about this impoverished focus, the more out of focus everything becomes. Act I is like quicksand. Most therapists contribute to helping clients sink deeper into this stuck place. They bring forth more information, provide alternative explanations, pose new questions, edit impoverished stories, ponder miracles, or attempt all kinds and orders of solutions. This approach helps keep everyone in Act I, potentially for the rest of the client’s life. Act I is a potential “burnout zone,” where therapists are most likely to think they have the most frustrating or boring job in the world.

The creative therapist waits for any inspiration, sign, imaginative leap, clue, or opening that points the way out of Act I. It doesn’t matter if the possible direction for movement is rational or irrational, enlightening or absurd, relevant or irrelevant. Any creative inspiration that might carry the therapist and client to a middle act is utilized. The therapist must go past his or her conditioning and have the courage to walk on an unknown road. This is when movement is felt for the first time. At this point, the therapist does everything possible to keep the session hanging in the interface between beginning and end, despair and hope, old and new (as opposed to falling back into the beginning). Here, chaos and craziness may make a house call to help nourish the process of transformation. This is where therapists think they have the most irrational job in the world.

Act II is the fulcrum—things can fall backward or forward. The more it teeters, the more likely the previously stuck frame will be loosened. As Archimedes once said: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move a world.” The creative therapist must move far enough away from Act I and stand on a fulcrum that enables the client’s paralyzed world to move.

Finally, the transformative leverage brought forth by creative interaction moves both client and therapist to Act III. Here, they find themselves in a new experiential reality where silver creative linings, rather than oppressive therapy clouds that call them to hide in a psychological shelter, are witnessed. Without effort, the sun shines in this act, even when it is dark. Creativity is in charge. Clients and therapists are surprised, often with a sense of awe, at how alive and generative their sessions have become. The process no longer feels like therapy; it has become a sizzling theatre of creative transformation. New possibilities, considerations, and scenarios for daily action are brought to light and initiated. This is when therapists think that they have the best job in the world.

That’s the whole of it. Everything else is mere detail.

The Creative Turn

Let me present this orientation in a slightly different way: Act I presents what the client brings to a session, “the presenting communications.” This act is the set-up, the beginning of a session, typically voiced as descriptions of problems, symptoms, and suffering. At this point, therapists need to avoid wallowing in the obvious and instead follow the advice of naturalist author Cathy Johnson (in Barron, Montuori, & Barron, 1997), who extols the importance of wandering and getting lost in a search for unknown experience. “Wandering is the itinerary” and it requires “a willingness to go beyond my safe, homey environment, my comfortable and comforting preconceptions” (p. 60). Wandering involves our being “unprogrammed” and open to finding an unexpected treasure lying just beyond our peripheral vision.

Act II moves the session to address a theme or topic that was completely unexpected and that, on the surface, seems to have little or nothing to do with the presenting communication. Inspired by an accidental encounter with the unknown, this is where the possibility for a creative turn takes place. As biologist Karry Mullis (in Barron et al., 1997) puts it, find what “you don’t know anything about and look at it for a long time, and you might learn something totally different” (p. 73). Attend to what the clients and you would otherwise bypass because it lies outside of problem or solution talk or outside of habituated meanings. Consider it an exit from therapy and a pointer toward possible transformation.

In Act II, the therapist holds onto the presence of something new and unexpected and works with it—both keeping it as a main theme and trying to amplify the intensity and validity of its presence. Act III takes place after therapy has successfully managed to creatively turn the theme and focus of the session into a “creative zone” that calls forth even more spontaneous creative moments. In this Part, there is no effort; everyone, clients and therapists alike, are in “the zone.” Anne Dillard (in Barron et al., 1997) captures this situation well: “Beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there” (p. 84).

Of course, the simple three-act structure may give way to more complexity. More acts are possible and they may involve unanticipated forms of movement. Mapping or scoring the acts of a session, no matter what form they traverse, helps us grasp the overall flow of a case as it is happening in real time or post hoc analysis. Like a musical score, scored therapy sessions show whether a conversation is moving (or not moving) from one act to another. Therapy that has been creatively awakened will move somewhere, as if having a life of its own, in the same way that an effective melody, story, screenplay, or theatrical play enacts movement.

Getting the Soil Ready with Good Timing

We should not forget thatin Barron et al., 1997) had this to say about creativity:

If the soil is ready—that is to say, if the disposition for work is there— [the seed] takes root with extraordinary force and rapidity, shoots up through the earth, puts forth branches, leaves and, finally, blossoms. I cannot define the creative process in any other way than by this simile. The great difficulty is that the germ must appear at a favourable moment, the rest goes of itself. It would be vain of me to try to put into words that immeasurable sense of bliss which comes over me directly [when] a new idea awakens in me and begins to assume a definite form. I forget everything and behave like a madman. Everything within me starts pulsing and quivering; hardly have I begun the sketch ere one thought follows another. (pp. 180–181)

Many years later, Frank Zappa (in Barron et al., 1997, p. 197) added his advice for how to compose. I have transposed it for therapy:

- Declare your intent to create a session.

- Start the session at some time.

- Help something happen over a period of time.

- End the session at some time.

- Get a part-time job so you can always continue doing sessions like this.

Tchaikovsky and Zappa provide another perspective on what we need to know in order to create transformative artistic work. The challenge is in finding out how to ready the soil, recognize the favorable moment, and know when to end. In other words, we need good timing and rhythm. Duke Ellington adds one more thing: “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.” Syncopation must be added to make the beat swing and that, in turn, gives life to music. The art of therapy similarly requires uplifting a session with rhythms that are capable of bringing forth creative movement.

To recapitulate, time in therapy most generally refers to moving through the beginning, middle, and end of each composition. Act I is the soil that must be prepared so that the ecology is ready to support new growth. In this stage, the previous dark nights of a client’s soul are utilized as tillage and compost, providing fertile soil for entry into another chapter of life. Act II introduces and plants a seed into the previously prepared therapeutic soil. This seed must receive appropriate attention. It requires watering and nutrition so that it may germinate and plant its roots deep into the dark soil. It initiates growth. Act III is harvest time. The seed has broken through the ground and is now fully in the light. It reaches upward and finds an awakening of fully embodied presence in the world. This stage helps bring forth the ripe fruit of therapeutic transformation.

Time in therapy also refers to the tempo and beat to which its movement is paced. Suffice it to say that the art of therapy has as much to do with timing, tempo, and vibrant rhythm as anything else. The therapist must move along with the natural unfolding of a session and be ready to accompany, support, and encourage its progression with inspiring rhythm, like a percussionist in a jazz trio. The “beat” applies not only to music but also to therapy. Without good rhythm, therapy can easily get off track, become disjointed, and lose its momentum. When the timing is alive, we can say that a session breathes and moves with its own spirited pulse.

Timing gives us another way of understanding change and transformation. It asks us to be entrained with our client, that is, rhythmically coordinated. This is another way of saying that we need to be in step with one another and swept away by the dance. It is the rhythm that grabs us, dances us, and moves us somewhere. This is the felt (as opposed to abstracted) “soul” of therapy.

I once met an old Lakota medicine man famous for presumably knowing how to make it rain. When I asked him how this was possible, he answered, “You have to be at the right place at the right time.” Being a rainmaker in therapy is the same: make sure you have good timing and are in step with the natural processes of change already surrounding you.

The execution of therapeutic creativity requires knowing when to introduce something, when to move on to the next thing, when to move from one act to another and, most important, when to end a session and send the clients back to their daily life. As a clinical supervisor, I have seen many sessions undo themselves by not ending when they should have. When a session is over, stop. If a session is well formed (it has gone through all three acts) after only 5 minutes, then get up and end it. Many of my sessions last between 20 and 30 minutes. They may be less or they may be more, depending on the song played, the dance danced, or the improv that has unfolded. It’s all in the rhythm.

Surprise Ending: Sometimes Paradigms Ain’t Worth a Dime

We should not forget that the three-act structure of a simple play was simply invented. Though called a “paradigm” for the construction of screenplays, once prescribed, it becomes what Geuens (2000, p. 107) calls a “super genre” that too easily dictates the only acceptable form for unfolding a play, film, or story. When asked about the traditional three-act paradigm, award-winning producer and screenwriter Diana Osberg (2006) responded, “Beginning screenwriters should learn the three-act structure thoroughly before they start breaking the rules” (p. 1). However, she qualifies this: “It appears that we human beings respond to the three-act structure in a primitive way. This...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I: Bringing It Forth

- Part II: Awakening a Session

- Part III: Therapy of Therapy

- References