![]()

Chapter 1

What is urban and environmental economics?

Vancouver, Canada

a. Overview

This text on urban and environmental economics introduces economics to the interlocking paradigms of both urban and environmental issues. Disciplines of both urban economics and environmental economics have often tended to take a separate and insular view from each other – it is one intention of this book to unify such thinking as well as extending thought into this field. Whilst doing this, the text more pragmatically demonstrates what urban and environmental economics entails within theory, concepts and practice. Furthermore, an introduction of techniques and tools within the subject will be outlined for the reader to use within both research and further studies.

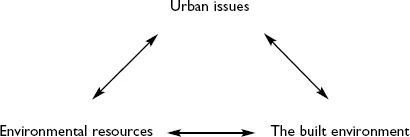

Conceptually, the focus of the book involves three interlocking strands that are viewed through an economic lens: the built environment; urban issues; and environmental resources (Figure 1.1). The built environment strand will connect to the spatial context of study; moreover, built-up areas at varying spatial scales will form the canvas on which discussion is expressed. This, for instance, involves analysis of neighbourhood effects within a city, or develops analysis of the agglomeration of cities within a larger urban conurbation or metropolis. Within these geographies, the economic concepts to be unearthed are those that integrate a multitude of themes within the urban issue strand. Themes of issues attached to urban geographies include education, such as examining how educational attainment is distributed over space; or those such as housing, where analysis involves an exploration of how the value of a neighbourhood correlates to household income and wealth. The third strand of environmental resources will draw together both urban issues and the spatial context of the built environment. For instance, the implications of de-urbanising and urbanising areas will be a multitude of needs and wants, which will have to be met, if possible using a scarce amount of available environmental resources. An urbanising world city will have wants such as building materials and energy needs, these will be met in part or in entirety, depending upon the availability of such resources – and thus the economic choices and decisions will play a significant role in how urban areas develop.

Figure 1.1 Three interlocking strands of urban and environmental economics

Source: Author

Within the three main strands, basic economic concepts for resource allocation are introduced that will be relevant to the planning, valuation and management of shared spaces. Economic concepts to be explored for application on urban and environmental matters include key issues such as considering the limits to growth and how choice is being played out within the built environment given the scarce environmental resources available. With respect to scarcity and choice, economic tools can be applied to provide more technical measurement of urban and environmental issues. Examples of economic tools include the use of cost-benefit analysis (CBA), and hedonic modelling that can provide more empirical evidence to support both arguments and decision-making in this field. Understanding and competence in these tools and models can aid in their use when applying them to both general and specific case studies and examples. For instance, more general comparative CBA could demonstrate the common and differentiating features of introducing a road or rail bypass for an urban area (e.g. London Cross-Rail), whereas the specific introduction of a housing estate to relieve residential pressures in an urban area could make use of a hedonic house price model that measures the dynamics (involving time) and magnitude (steepness of change) of particular independent variables such as education and health in relation to changes in a dependent variable such as house price.

b. Relevance and importance

At the forefront of urban and environmental economics is the pressing issue that urban areas are set to become the focus for the global effort to curb climate change. It is argued that the world's cities are responsible for about 70 per cent of emissions, yet they only represent 2 per cent of the planet's land cover (UN Habitat, 2011). More dramatically, it has been argued that there will be a collision between climate change and urbanisation if no action is taken. According to a recent UN report, an estimated 59 per cent of the world's population will be living in urban areas by 2030. Plus, every year, the number of people who live in cities and towns grows by 67 million – 91 per cent of this figure is being added to urban populations in developing countries (ibid.). Reasons why urban areas are energy-intensive is due to increased transport use, heating and cooling homes and offices and economic activity to generate income.

As well as cities’ contribution to climate change, towns and cities around the globe were also vulnerable to the potential consequences. These include an increase in the frequency of warm spells/heatwaves over most land areas, a greater number of heavy downpours, a growing number of areas affected by drought and an increase in the incidence of extremely high sea levels in some parts of the world. Economic problems will be generated from these physical risks posed by future climate change, with, for instance, some urban areas facing difficulties in affording to provide basic services following change. For example, these changes will affect water supply, physical infrastructure, transport, ecosystem goods and services, energy provision and industrial production. At a more microscale, local economies will be disrupted and populations will be stripped of their assets and livelihoods. Disparities of income and wealth at a macroscale can also be extrapolated with arguments that those poorer urban areas are doubly disadvantaged, with a lack of wealth to mitigate against climate change whilst also being subject to its damaging effects.

c. Introducing urban and environmental economics

In understanding what urban and environmental economics entails, an overview of its importance as a subject area and its relevance to both knowledge and practice will need to be determined. Its evolution by integrating economics to both urban issues and environmental concerns within the built environment involve both historical and current economic thinking within the fields of urban studies and environmental science. As such, the attributes and historical context of urban and environmental economics will, initially, be revealed as a subject in itself and in its application to policy.

Isolated constituent parts of what is meant by urban economics and environmental economics are defined and illustrated while highlighting the common ground in which the two disciplines are intertwined. The concepts of space using the urban or built environment are also introduced to provide clarity to ‘where’ the focus of discussion is being placed. This is particularly important, as not only are processes operating in urban areas, but there is connectivity between built environments situated in space (e.g. roads, rail networks, airports), which have demands on natural resources. In considering these connectors of the built environment, economic aspects can be attached, such as how much and what value of natural resources (e.g. energy) is supplied external to an urban area (e.g. a power station) and being transmitted and consumed internally by a particular densely populated city or region. Natural resources as part of this systematic thinking is also introduced as a perspective in the subject – especially in terms of how environmentalism and the sustainability agenda operate in relation to urban areas, plus further coherence in distinguishing between what is meant by the ‘natural’ and ‘built’ environment. For instance, urban green space (i.e. parks) and green belts as the natural environment may be conceived differently, plus changes in land use (e.g. to brownfield) may render them sites that are no longer considered ‘natural’.

Different paradigms in what is considered environmental or urban in economics should be clarified and are also considered in this text (Chapter 2). Two significant and distinctive types of thinking are more modern western environmental resource economic (ERE) paradigms and more ecological economic (EE) paradigms. The former approach, environmental resource economics, tends to consider largely classical economic ideas in relation to the environment, such as internalising into the market the external cost of pollution. The latter paradigm, ecological economics, tends more to integrate elements of economics, ecology, thermodynamics, ethics and a range of other natural and social sciences to provide an integrated and biophysical perspective on environment–economy interactions (Van den Bergh, 2000). Links to ecological economics will be drawn on in this text, as an ecological approach will introduce critical linkages to how urban areas produce and consume environmental resources.

The appropriation of economics to both the built and natural environment is no doubt complex and generates different and often vociferous opinion on what approaches ‘are’ and ‘ought’ to be carried out by economists. Urban and environmental economics according to economists, both individually and institutionally, is the focus of Chapter 3. This outline of significant thinkers integrates both normative and empirical analytical dimensions. Normative statements are primarily non-falsifiable statements or value judgements of what should or ought to be – a normative statement could argue that rapid urban sprawl should be halted as it is detrimental to sustainable development. Positive statements are more empirically driven to provide information that can be made falsifiable or tested for its basis in ‘fact’ – an empirical statement could be that the global proportion of urban population rose dramatically from 13 per cent (220 million) in 1900, to 29 per cent (732 million) in 1950, to 49 per cent (3.2 billion) in 2005 (UN, 2005).

Key writers to introduce urban and environmental economic thinking include Thomas Malthus (1766–1834). The key concern for Malthus was the rapid increase in population to urban areas as a process of urbanisation, and he intonated that while the population grows exponentially, the supply of resources such as food and shelter can only grow linearly. This in turn puts a limit on the size of population a given area can support and, as a result, generates a problem of the growth and distribution of resources within the built environment. As well as Malthus, other classical economists have been attached to urban and environmental thought. An influential writer is David Ricardo (1772–1823) who made a significant connection between the prices of natural resource produce, such as food, with economic concepts, such as comparative advantage and rents.

Infinite economic advance and the ability to feed populations took a different direction with the influential writing of John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Mill, who initially took a libertarian free-market slant, viewed economic growth in tune with natural cycles, where growth was not an endless process but one that will eventually reach a lasting dynamic equilibrium. Attachment of these cycles of economic growth was at the forefront of thinking for Mill during a period where material advancement held sway. Later writing incorporated social welfare ideas into economic thought, where, for instance, well-being could be maximised for all when the greatest consumption capacity is for the greatest number of individuals. Social welfare in urban economics is particularly important in contemporary thought, with a concern for internal social costs, such as those attached to concentrated poverty, largely located in urban areas. This in turn brings focus away from pure economic growth models and towards issues such as redistribution of income and wealth within and between urban areas.

Arthur Pigou (1877–1959) is discussed with respect to social concerns and environmental resources in the urban environment. Pigou's work on income distribution within welfare economics is important, especially as it was argued that a greater balance of wealth distribution could increase greater consumption and growth. His work on externalities also firmly fixed his influence within the realm of environmental economics. For instance, as a corrective measure to counter external costs from pollution, a series of ‘Pigovian taxes’, such as petrol or carbon taxes (also referred to as ecotaxes or the Green Tax Shift), have been endorsed.

More recent institutional approaches have been developed by groups such as the Club of Rome (1968), which involved former heads of state, UN bureaucrats, high-level politicians and government officials, diplomats, scientists, economists and business leaders from around the globe. Their fundamental impact, with regards to environmental economics, was to publish on the limits to growth as a result of rapidly growing populations and finite resource supplies (Meadows et al., 1972). It can therefore be recognised that some of the larger fundamental economic questions regarding scarce environmental resources and growing population demands keep Malthus as relevant today as in the eighteenth century.

At a more general level, urban and environmental economics are primarily concerned with the basic economic problem of unlimited wants and scarce resources (Chapter 4). For this book, the environmental resources,‘wants’, are situated with respect to urban spaces. For instance, meeting the ‘want’ of water in urban areas will be dependent on how society decides to produce and distribute the resource. These decisions centre on choice (if there is a choice), and if resources are scarce, the production and distribution will be made via a system of choosing alternative uses, through which the need could be met.

Choice in the use of resources for production is important in understanding how society decides the what, how and to whom in an urban environment. If there is a choice it will mean that there is an opportunity forgone on the alternative – this is what is referred to as an ‘opportunity cost’. If there is a choice to use public funds for a new school, there will be an opportunity cost of what alternative funds could have been used – for example to build a hospital or community centre. These trade-offs in choice are conceptualised in basic models such as a PPB (production possibility boundary) where the trade-off between two commodities such as guns or butter can be visualised, and the optimum amount of production for both commodities can be demonstrated. Conceptual models such as the PPB are covered in Chapter 4, and this particular idea of a PPB can begin to demonstrate that choices have to be made and opportunity costs considered as there is a finite amount of goods and services attainable if growth is static.

Economies do expand and contract. This raises the possibility that more wants can be satisfied. But whether there is a limit to growth is the focus of Chapter 5. As discussed with respect to Malthus, environmental resource constraints may keep populations in check and constrain wealth. An exploration of what may restrain growth with reference to the built environment is important. For instance, if cities are the main hub and engine of employment and output, the ability for the city to grow economically may depend on its ability to house its workers or have available space to develop new industrial or commercial units. Key restraints to growth explored are those such as inadequate or inefficiently used natural resources, rapid population growth, inadequate human resources, cultural barriers, inadequate domestic savings, infrastructure and debt. Interesting thought experiments are brought forward such as asking what the consequences would be if growth was unconstrained and the free market was allowed to ‘let rip’. An example could be to consider whether a complete relaxation of planning laws on green belts surrounding cities would add or subtract value over time.

d. Integrating theory of micro and macroeconomics

To further understand urban and environmental economics, the concept of markets in a microeconomic context is useful and is the principal focus of Chapter 6. As an introduction it considers what the economist Adam Smith (Smith, 1776) referred to as an ‘invisible hand’, where the forces of the producer and consumer interact, whilst tending towards an equilibrium of price and quantity for a particular market good or service, such as housing in a city. This particular system of production, consumption and distribution through market forces is the underlying mechanism for a predominantly market orientated economy where producers make a large number of decisions about what is produced. This is opposed to a more government-controlled decision-making system operating within a command economy. Extremes of complete free market and command economies are not polarised in reality and will tend to have a mix (i.e. a mixed economy), with leanings towards one particular model depending on its economic, historical and political context.

Free(er) markets are often cited as being more efficient in balancing the demand and supply of goods and services, although Chapter 7 will begin to demonstrate ways in which the market can fail. Market failure is seen when resources cannot be efficiently allocated between producers and consumers. For example, all of the costs generated by a coal power station may not be completely internalised if there is an external cost of pollution when producing energy. Study of externalities demonstrates the difficulty of valuing ‘free’ environmental resources that are used in the built environment.

Some social and environmental valuation techniques to be covered in Chapter 7 include: the socially optimal level of output, where the assimilative capacity of an externality is reached and therefore at an optimal level; and the willingness to pay (WTP) and willingness to accept (WTA) principles, which...