This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

East European Cinemas

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Eastern Europe has produced rich and varied film cultures--Czech, Hungarian, and Serbian among them-whose histories have been intimately tied to the transition from Soviet domination to the complexities of post-Communist life. This latest volume in the AFI Film Readers series presents a long-overdue reassessment of East European cinemas from theoretical, psychoanalytic, and gender perspectives, moving the subject beyond the traditional area studies approach to the region's films. This ambitious collection, situating Eastern Europe's many cinemas within global paradigms of film study, will be an essential work for all students of cinema and for anyone interested in the relation of film to culture and society.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access East European Cinemas by Anikó Imre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

gender identity and representation

one

second world-ness and transnational feminist practices

agnieszka holland's

kobieta samotna (a woman alone)

kobieta samotna (a woman alone)

katarzyna marciniak

If the world is currently structured by transnational economic links and cultural asymmetries, locating feminist practices within these structures becomes imperative.

—Inderpal Grewal and Caren Kaplan,

Introduction to Scattered Hegemonies:

Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices

Introduction to Scattered Hegemonies:

Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices

I will start with a pedagogical experience that inspired this essay. In 2003, I taught a newly designed graduate seminar, “Transnational Feminist Practices.”1 My students were intrigued by exploring this new field of transnational feminist cultural studies. The seminar combined the study of diasporic cinema and current discourses of transnationality in order to examine border and transcultural identities in the global contexts of exilic dislocation, patriarchal violence, and ethnic cleansing. For all my students, this was a fresh intellectual experience. As foundational texts for the seminar, we read Inderpal Grewal’s and Caren Kaplan’s work answering the question, “Why do we need a theory of transnational feminist practices?” We then moved to essays by Meena Alexander, Leo R. Chavez, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Stuart Hall, Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Nawal el Saadawi, Ella Shohat, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Trinh Minh-ha, and others. We investigated critiques of “global feminism” and “global sisterhood” with the understanding that, as Kaplan claims, these discourses “have naturalized and totalized categories such as ‘Third World women’ and ‘First World women.’”2 Probing these readings, it became clear that one of the main concerns of the field is to trouble the First World/Third World binary and to scrutinize the often subtle operations of the Eurocentric logic that historically patronizes non-Western spaces and peoples, while endlessly privileging “First Worldness.” It also became clear that the discussions of Second World women in relation to transnational feminist studies were nowhere to be found in the essays we studied.

As a class, we found ourselves in an ambivalent position when we got to the rubric of the Second World by way of screening Agnieszka Holland’s 1981 film Kobieta Samotna (A Woman Alone). The notion of Second Worldness was a puzzle for my students as they acknowledged they were unfamiliar with its conceptual application. I came to see their lack of “knowledge” as a product of a certain cultural amnesia that manifests itself in the discursive elision of post–Berlin Wall communities that, I think, are erroneously treated by many scholars as already Western. Within such a conceptual paradigm, the category of the Second World, considered as no longer useful or relevant, is a relic belonging to the Cold War rhetoric and the socialist era. Additionally, as my students pointed out, the postsocialist-communist Eastern and Central European regions are obviously familiar to them, but under the notions of, for example, Balkan studies, or East European studies—categories typically dissociated from theories of transnational feminisms.3

Analyzing the dynamic of our seminar, largely dictated by our readings, I realized that some of my students, even prior to their learning about the field of transnational feminist cultural studies, were already familiar with the need to trouble the First World/Third World binary and to resist the patronizing gestures of “global sisterhood” that privilege the agency of mainly white, Western women. However, because the category of Second Worldness hardly ever shows up in these theoretical discussions, the need to think about this geopolitical space in the context of transnational feminisms was quite a challenge. I write this essay taking up this—admittedly ambitious—challenge. My intention is to expand the scope of transnational feminist studies, to stretch its parameters, so that the voices and perspectives from the Second World may find their way into the field that many consider a radical and indispensable direction for feminist studies.4

the context of transnational feminist cultural studies

Aihwa Ong once remarked that “besides the poor, women, who are half of humanity, are frequently absent in studies of transnationalism.”5 Initiated by such U.S.-based feminists as Grewal, Kaplan, Mohanty, Shohat, and Spivak, the field of transnational feminist cultural studies has developed in response to this absence. This new scholarly area combines transnational studies with multicultural feminist theories. Discussing transnational feminist practices as a critical pursuit grounded in historical specificity, Kaplan argues that “[p]ostmodern theories that link subject positions to geopolitical and metaphorical locations have emerged out of a perception that periodization and linear historical forms of explanation have been unable to account fully for the production of complex identities in an era of diaspora and displacement.”6 The main goal of the field is thus to link the studies of postmodernity and global economic structures with issues of race, imperialism, nationalisms, and critiques of global feminism. As my class came to find out, despite its intended global scope, the field omits perspectives from the Second World. Why does the field continue to operate within the critique of the First World/Third World binary? I believe the answer is twofold.

First, many feminist thinkers whose voices are prominent in multicultural, diasporic debates in the United States come from the places traditionally labeled as the Third World. As a result of such a politics of location, the main discussions have focused on critiquing the oppressive West/non-West dichotomy and on showing how, to use Trinh’s words, “there is a Third World in every First World and vice-versa.”7 The dominant feminist discourses, even those that advocate “polycentric multiculturalism,”8 “anti-racist, multicultural feminism,” or “radical or critical multiculturalism,”9 operate discursively within the disruption of the First World/Third World axis and say very little about the ambivalent territory of the postcommunist Second World.

A second reason for the neglect of Second World feminist voices is motivated by the treatment of the Second World as a bygone category. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, for example, in their groundbreaking book Unthinking Eurocentrism, commented on the nonexistence of the Second World.10 Such claims contribute to the false impression that communities once behind the Iron Curtain are already Western. This belief ignores the fact that Central and Eastern European regions, for a long time placed in Western imagination “behind the Wall,” continue to be treated as the “other” Europe, the impoverished cousin to the “real” thing, a treatment that consolidated the identity of “true Europeans” who see themselves as legitimately and “purely” Western.

As a result of such conceptualizations, the field of transnational feminist studies hardly ever gestures toward feminist voices from the Second World. Hence, despite their radical potential, feminist debates operate within a restricted focus—unintentionally, I believe, limiting the meanings of the notion of the transnational. My thinking in this regard has led me to the following questions: What are the implications and consequences of the discursive erasure of the Second World? What might be gained by reviving this category? Bringing into focus Holland’s Kobieta Samotna, a Second World narrative that is formally and thematically connected to the trope of transnational crossings, my intention is not merely to recover the forgotten space of the Second World; neither do I wish to create the impression that the Second World needs to compete for attention with the Third World. The notions of the First, Second, and Third Worlds are obviously reductive ideological constructs that support the primacy of the First World. I share, for example, Shohat and Stam’s contention that “all these terms, like that of the ‘Third World,’ then, are only schematically useful; they must be placed ‘under erasure,’ seen as provisional and only partly illuminating.”11 At the same time, however, I am curious about the impulses behind an incessant stress on the idea that the “Second World is no more.”12 Thus, I see the need to acknowledge and investigate the complexity of transnational crossings within a more global network.

transnational desires

[T]he misleading impression [is] that everyone can take equal advantage of mobility and modern communications and that transnationality has been liberatory, in both a spatial and political sense, for all peoples.

—Aihwa Ong, Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality

Kobieta Samotna is Agnieszka Holland’s last film made in Poland before she left the country in 1981.13 Since then, she has produced her films within transnational contexts—in France, Germany, and the United States—and has achieved international prominence for such productions as Bittere Ernte (Angry Harvest, 1985), To Kill a Priest, (1987), Europa, Europa (1990), Olivier, Olivier (1991), The Secret Garden, (1993), Total Eclipse, (1995), and Washington Square (1997). Of all of the films in her oeuvre, Kobieta Samotna stands out as a particularly original, unforgettably poignant narrative.14 The film represents a socially underprivileged, working-class single mother struggling to support herself and her eight year-old son, Boguś. The originality of the film comes precisely from its focus on a female protagonist, Irena (Maria Chwalibóg), placed at a pivotal moment in Polish modern history—between the beginning of the Solidarity movement and the end of the communist era. Unconventionally, the narrative does not take the side of either political party, choosing not to condemn the communist system in favor of Solidarity. Instead, through privileging a woman’s experience—her struggle amid physical exhaustion to secure food and shelter for herself and her son—the film becomes a devastating critique of both parties, showing us how for either of them, a character like Irena is of no concern: “I am a nobody. I didn’t fight in the war, I don’t have a car. I work for pennies; nobody respects me.” Those bitter words that Irena utters stress her awareness of her abjected position as a poor woman from the lowest social stratum.

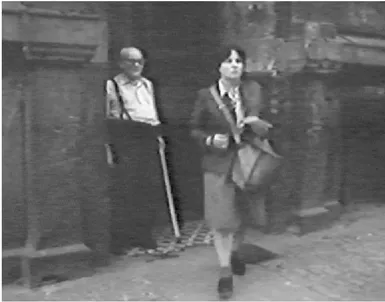

Figure 1.1 Irena (Maria Chwalibóg), a mail carrier, on her route.

Crucially, in its depiction of female aloneness, misery, and desperation driven by Irena’s economic status and particular circumstances (she has a long history of having been beaten, first by her father and then by her husband), the film carefully avoids clichéd markers of sentimentality. Kobieta Samotna feels like an intense paradocumentary, brutal, even cynical, in its unrelenting honesty—unromantic, unemotional, exposing the grimness of life without a weepy narrative that would elicit pity, thereby positioning the spectatorial gaze at a “safe” distance. Rather, through discomforting close-ups, the tight framing of bodies onscreen, a sparse soundtrack that favors ambient sound, mostly natural lighting, and authentic locations the film foregrounds various tactics of identification that bind the audience’s gaze to the diegetic tonality of oppression and desperation. As I will discuss herein, the particular suture the film offers is one without release: there is absolutely no loosening of the narrative hold, no redemption, no ejection from the images of abjection that permeate the narrative. Death, garbage, disabled bodies, decomposing mise-en-scène, the tonality of suffocation, and cultural and social claustrophobia dictate a haunting tempo; even sex is abjected as the representation of intimate encounters between Irena and her friend Jacek (Bogusław Linda) stresses bodily discomfort and is, ultimately, painful to watch.

The climax of Kobieta Samotna ends on a heart-wrenching, albeit unsentimental, note and underscores what I see as a main argument of the film: a desperate yet futile desire for mobility; a wish to escape to a West imagined as a liberatory space. The film exposes a hunger to become “transnational”—that is, to become a mobile subject beyond the confines of one’s nation. Simultaneously, the narrative shows trans-nationality as an unattainable location, a mirage pursued by characters doomed to various complex locations of abjection.15

Jacek, having suffocated Irena to death with a pillow in a motel room, walks into the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw. The embassy is marked as a place of desire: this is where one applies for visas to travel to the United States and where one can brush up against the vision of a better life. A fenced-off, luxurious island of the West amid the dilapidated Polish landscape, the embassy is the space that promises mobility, a life away from the grim brutality of communist Poland in 1981. Jacek is disabled; he drags his stiff leg. His difficulty walking (both visually and metaphorically) underscores his hindered mobility. His head bizarrely wrapped in dark tape, he enters the embassy clutching a suitcase with a blinking light that he nervously switches on and off. He appears awkward, clumsy, and disoriented. Somewhat shyly approaching the security booth, Jacek explains his strange appearance to a guard whose frozen posture and onward gaze remain undisturbed; “You know,” he says, “I had to wrap it up. I was afraid the skull might . . . crack open. I had to wrap it up because it fell apart.” When he is finally approached by a security officer, he explains that his suitcase is full of explosives and demands a visit with the ambassador and a trip to the United States. The officer treats him cautiously, but his condescending tone clearly suggests that he assumes Jacek is emotionally disturbed, not to be taken too seriously. As the officer’s voice gently coaxes Jacek to sit down and put the suitcase aside, we watch the culminating point of the sequence, ironically eerie in its evocation: still embracing the suitcase with his arms,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- list of illustrations

- acknowledgments

- introduction east european cinemas in new perspectives

- part one: gender identity and representation

- part two: (post)modernist continuities

- part three: regional visions

- notes on contributors

- index