About this book

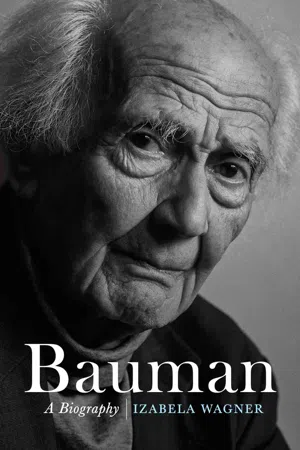

Global thinker, public intellectual and world-famous theorist of 'liquid modernity', Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017) was a scholar who, despite forced migration, built a very successful academic career and, after retirement, became a prolific and popular writer and an intellectual talisman for young people everywhere. He was one of those rare scholars who, grey-haired and in his eighties, had his finger on the pulse of the youth. This is the first comprehensive biography of Bauman's life and work. Izabela Wagner returns to Bauman's native Poland and recounts his childhood in an assimilated Polish Jewish family and the school experiences shaped by anti-Semitism. Bauman's life trajectory is typical of his generation and social group: the escape from Nazi occupation and Soviet secondary education, communist engagement, enrolment in the Polish Army as a political officer, participation in the WW II and the support for the new political regime in the post-war Poland. Wagner sheds new light on the post-war period and Bauman's activity as a KBW political officer. His eviction in 1953 from the military ranks and his academic career reflect the dynamic context of Poland in 1950s and 1960s. His professional career in Poland was abruptly halted in 1968 by the anti-Semitic purges. Bauman became a refugee again - leaving Poland for Israel, and then settling down in Leeds in the UK in 1971. His work would flourish in Leeds, and after his retirement in 1991 he entered a period of enormous productivity which propelled him onto the international stage as one of the most widely read and influential social thinkers of our time. Wagner's biography brings out the complex connections between Bauman's life experiences and his work, showing how his trajectory as an 'outsider' forced into exile by the anti-Semitic purges in Poland has shaped his thinking over time. Her careful and thorough account will be the standard biography of Bauman's life and work for years to come.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A Happy Childhood ‘Under Such Circumstances’

A significant birth place, a critical time …

I cannot avoid history. History decreed that the state of ‘being Polish’ has been through centuries a question of decision, choice and action. It has been something one had to fight for, defend, consciously cultivate, vigilantly preserve. ‘Being Polish’ did not mean guarding the already well formed and marked frontiers, but rather drawing the yet-not-existing boundaries – making realities rather than expressing them. There was in Polishness a constant streak of uncertainty, ‘until-further-noticeness’ – a kind of precarious provisionality that other, more secure nations know little about.Under such circumstances one could only expect that the besieged, incessantly threatened nation would obsessively test and re-test the loyalty of its ranks. It would develop an almost paranoiac fear of being swamped, diluted, overrun, disarmed. It would look askance and with suspicion at all newcomers with less-than-foolproof credentials. It would see itself surrounded by enemies, and it would fear more than anybody else the ‘enemy within’.Under such circumstances one should also accept that the decision to be a Pole (particularly if it was not made for one by the ancestors so distant that the decision had time to petrify into rock-solid reality) was a decision to join in a struggle with no assured victory and no prospect that victory would ever be assured. For centuries, people did not define themselves as Poles for the want of easy life. Those who did define themselves as Poles could rarely be accused of opting for comfort and security. In most cases, they deserved unqualified moral praise and whole-hearted welcome.That the same circumstances should lead to consequences pointing in opposite directions, clashing with each other and ultimately coming into conflict – is illogical. Well, blame the circumstances. (Bauman, 1986/7: 21–2)

In 1853, naturalized Jews were elected to the city council for the first time; their number exceeded the number of Polish delegates, worsening the far-from-perfect relationship with the Polish population … For Poles striving to regain their lost independence, Germanized Jews who flaunted their Prussian loyalty and servility became in some cases a more hostile group than the Germans themselves. Jews of Poznań would experience this hostility particularly poignantly after WWI. (From the official site of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)12

Table of contents

- Cover

- Front Matter

- Introduction

- 1 A Happy Childhood ‘Under Such Circumstances’: Poznań (1925–1932)

- 2 A Pupil Like No Other: Poznań (1932–1939)

- 3 The Fate of a War Refugee (1939–1944): Poznań–Molodeczna

- 4 Russian Exodus, 1941–1943: Gorki and the Forest

- 5 ‘Holy War’: 1943–1945

- 6 Officer of the Internal Security Corps: 1945–1953

- 7 ‘A Man in a Socialist Society’: Warsaw 1947–1953

- 8 A Young Scholar: 1953–1957

- 9 Years of Hope: 1957–1967

- 10 Bad Romance with the Security Police

- 11 The Year 1968

- 12 Holy Land: 1968–1971

- 13 A British Professor

- 14 An Intellectual at Work

- 15 Global Thinker

- Conclusion: Legacy

- Appendix: Working on Bauman

- Bibliography

- Index

- Ebook plates

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app