one

The Spiral and Modes of Inquiry

Options, Choices, and Initial Decisions

This chapter describes how your research journey might begin:

Thinking about professional concerns in the larger context of music teaching and learning;

Filtering one concern out of several by cursory and reflective reading.

The chapter puts into scholarly perspective what likely originated in personal experience and casual observation. Employing both cursory and reflective reading skills, you learn to look for specific characteristics in a variety of publications.

Introduction

The research journey begins with accepting that “who, what, where, when, why, and how” questions relative to areas of concern are not always easily answered by simply looking them up on the Internet or by asking experts in the field. Second, hardly any answer remains the same once and for all. This is why the “think–read–observe–share” cycle is ongoing: Thinking leads to observing or reading, which may lead to the possible modification of once accepted answers; or reading leads to observations that may make you question previous assumptions or thoughts. Finally, sharing your insights with peers, colleagues and—possibly—the public at large may trigger responses that cause yet more thinking, reading, and observing on your part.

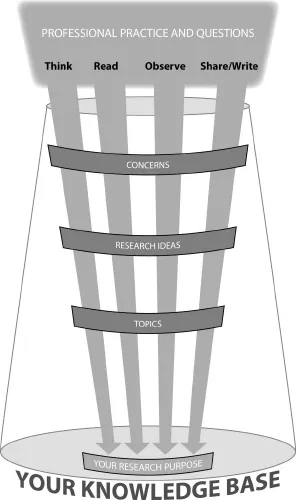

The quest is characterized by exploring and articulating (“framing”) researchable questions from which you select any one for further examination. The activities become the filters by which you work toward the goal of selecting a purpose upon which a complete study can be built. You may visualize it as shown in Figure 1.1.

Notice that the illustration actually contains two cone images—one inverted, the other upright—that relate to each other. Its purpose is to point out that when you engage in thinking, reading, observing, and sharing with increasing specificity, your knowledge base about the field broadens; one cannot happen without the other. Early in the filtering process, you may be inclined to spend much time on thinking/reading, less on observing/sharing (preferably in writing) your thoughts and findings with your peers. Ideally, however, you should move back and forth between all four activities long before you have fully finalized your plans for executing an actual research project.

FIGURE 1.1 The Search Process Visualized

Do not be surprised if the spiraling process does not unfold as neatly as visualized in our “textbook description.” In fact, at times, you may feel as if the reading and thinking goes in circles, that is, nowhere. This is the proverbial brick wall all scholars run into occasionally, an experience you also know from practicing your instrument. Be assured that moments like that actually may be signs of progress. In the process of exploring, framing, and selecting ideas and topics, uncertainties are inevitable because you do not always feel comfortable in letting one topic go in favor of pursuing another one.

Thinking, reading, observing, and sharing/writing may overlap or take place side by side, albeit at different levels of specificity and clarity. Therefore, share your concerns, ideas, and topics with friends and colleagues so that you learn to frame your thoughts in a terminology familiar to your peers. At the same time, find published evidence in support of your concerns.

Many terms could be used to label the levels of specificity that guide the filtering process. Our labels, chosen deliberately without being necessarily binding, are research concerns, ideas, topics, and purpose. Other choices might be equally suitable as long as it is understood that the research process evolves through stages of increasing specificity by which a purpose for your project becomes clear to you.

To describe the aim of a research project, some replace “research purpose” with “research question”; still others refer to it as the “research problem.” Consider using the term “research problem” cautiously because it tends to imply that a resolution is expected as the outcome of all studies. In fact, some research, especially in the philosophical realm, may generate more questions rather than solve any one problem in particular. In that case, you might prefer to call the focus of your study the “critical issue” or the “problematic.”

Framing Concerns About Music Teaching and Learning

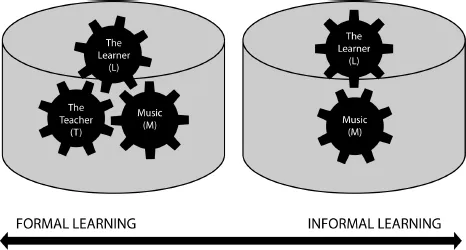

When one defines music education as the study of the learning and teaching of music, the components that foremost frame research in music education tend to be the learner (L), the subject matter of music (M), and the teacher (T), either by themselves or in interaction with each other. To capture this interconnectedness between the component parts, Figure 1.2 shows them as “cogs” (similar to bicycle gears) that cause each other to move, thus resulting in particular processes of learning and teaching.

In the instructional formality of school music in which the teacher guides nearly all musical interactions, the three components shape the interplay of actions in the classroom or rehearsal. Referring to such learning situations as schooling, formal, or instructor-guided learning suggests that they take place wherever teachers, assigned mentors, or otherwise appointed or declared superiors oversee the instructional process. Outside of school—away from teachers, mentors, or mediating guides—the learner interacts directly with the music, which changes the ongoing dynamic between learner and subject matter. Calling such situations informal learning does not imply a learning situation that is less important or effective than what goes on in the formality of institutional settings. The opposite may be the case. Presently, both terms—formal and informal learning—are stipulated definitions, still awaiting systematic examination and verification by further evidence. Their presence in this chapter simply acknowledges that the way in which music learning takes place impacts its results.

FIGURE 1.2 The Interconnectedness Between Formal and Informal Music Learning Situations

Some Thoughts by the Students in RC 533

Most of the students in RC 533 were initially more interested in issues related to formal music instructional processes than in informal ones. They thought of themselves as teachers who, with varying degrees of experience, had practical “who, what, where, when, why and how” questions about their own involvement in everyday instructional practices. To illustrate:

Carlos asked about technology as an aid for teaching general musicianship skills, such as composing and music analysis/theory. He also wondered how he could best measure the benefits of technology as a tool for teaching musicianship skills. By looking at the teacher–learner–music model, he realized that focusing on the learners—his students—would prompt him to ask about the technology expertise his students brought to the instructional process. Coming from the vantage point of the music itself, Carlos wondered what type of music would best connect his students’ interests to the musical choices mandated by the curriculum. These questions evolved into thinking about the purpose of music appreciation class, at first perhaps a less tangible concern for him, but one that grew in importance the longer he thought and read up about the teaching of music to students of varying ages and diverse musical backgrounds, and interests.

Christy's efforts to articulate several areas of concern stemmed from her question about being an effective studio teacher. “How do I teach differently from what others say or do?” she asked. “What and how do others teach?” “How (and why) do I know that I am effective?” When focusing on music (the music cog in Figure 1.2), Christy—like Carlos—thought about other pedagogues before her. As a result, she moved away from exclusively focusing on herself. Instead, historical questions began to come to the forefront: Who has become known as a string pedagogue? What have they become known for and what approaches did they use? What repertoire choices did they make and how has their legacy influenced today's pedagogies?

Both Christy and Carlos had begun to broaden their interests. Christy's example in particular illustrates how an original concern (her own effectiveness as a studio teacher) can develop into a question (previous pedagogy models) of historical significance (what can knowledge about the past teach us about the present?). Clearly, considering whether your own areas of concern deal with ideas about teaching or specific actions by your pupils, with events of the past or the present adds a new dimension to your inquiries. But Christy could also have broadened her initial concern by probing relationships between herself and her students, possibly even adding issues of repertoire choice, teaching strategies, or her students’ home backgrounds to the list of ideas she began to gather.

Exploration: Pause for a Moment and Think

Consider what has come to your mind thus far: Are your interests situated in institutional learning and teaching or in how learning might take place outside of school? Are you looking into the past like Christy had begun to do, or are you more intrigued by what happens in the present? Are you primarily interested in your or other teachers’ behaviors and resultant actions or does the world of ideas about music pique your curiosity? If the latter, how does the world of ideas in music relate to thoughts about education and formal instruction? What questions fascinate you and how could you best articulate them?

Answers to any of the questions posed in the above assignment refer to what we call modes of inquiry. Understanding what they are and knowing differences among them may benefit how you might best articulate specific concerns about various learning and teaching settings. The better and more succinctly you frame such concerns, the stronger all subsequent steps in your research are likely to be.

Modes of Inquiry

All research begins with asking questions about that which is to be examined. Now that you have begun that process yourself, scrutinize the nature of those questions. What specifically are you asking about? Are you interested in the past or in the present; in actions, behaviors, and experiences; or in the study of ideas?

A concern about past events, behaviors, and/or documented experiences would likely lead to a historical study; examining past and present ideas would fall under philosophical inquiries; and examining present events, behaviors, actions, and/or experiences would be empirical in nature—regardless of which methods were used. Interestingly, the etymological origin of all three terms goes back to “learnedness, wisdom, and experience.”

“Empirical” derives from the Latin empiricus (or from the Greek empeirikos, empeira, and/or empeiros), making reference to experiences that come from “living in the world” as opposed to knowledge that results from studying written documents. A characteristic derived from “learnedness through experience” brings us to the “learned” or “wisdom loving” person. In Greek, philosophos means the same: The person who loves wisdom. The Latin histor means “learned man,” suggesting a close connection between “lover of wisdom” and “learned man.” A histor, philosophor, and empiricus therefore purs...