eBook - ePub

Functional Behavioral Assessment

A Special Issue of exceptionality

This is a test

- 88 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 2000, Functional Behavioral Assessment is a valuable contribution to the field of Education.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Functional Behavioral Assessment by George Sugai, Robert H. Horner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Overview of the Functional Behavioral Assessment Process

George Sugai, Teri Lewis-Palmer, and Shanna Hagan-Burke

College of Education University of Oregon

College of Education University of Oregon

The research literature is replete with examples that support the use of the functional behavioral assessment (FBA) process. In addition, the 1997 amendments to the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act have recognized the importance of the FBA process for students who display significant problem behavior in schools. However, clarity about the specific definition and features of the FBA process is just beginning to be developed. The purpose of this article is to provide a general description of the features and steps of the FBA process.

Although the 1997 amendments to the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) emphasized the use of functional behavioral assessment (FBA) in schools, the idea of looking at behavior within the context in which it is observed has been in the literature since the early 1900s. Discussions about functional analysis and functional relationships began with the early writings and works of Ivan Pavlov, John Watson, Edward Thorndike, Fred Keller, B. F. Skinner, and other early behavioral psychologists. They demonstrated that behaviors do not occur in a vacuum but in a lawful and predictable manner that is related directly and functionally to environmental events. Beginning with the 1968 publication of Baer, Wolf, and Risley's seminal article "Current Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis" in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, the behavior analytic approach has grown to be an important means of improving behavioral outcomes for individuals with disabilities. A significant body of research has demonstrated the effectiveness and utility of a functional analytic approach, especially for individuals with developmental disabilities (Blakeslee, Sugai, & Gruba, 1994; Carr et al., 1999). In recent years, the application and usefulness of functional assessment-based behavior support planning (BSP) have been extended to a range of individuals, including those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and emotional and behavioral disorders as well as those without specified disabilities (Broussard & Northup, 1995; Dunlap, White, Vera, Wilson, & Panacek, 1996; Kern, Childs, Dunlap, Clarke, & Falke, 1994; Lewis & Sugai, 1993; Lewis-Palmer, 1998; Sasso et al., 1992; Umbreit, 1995).

IDEA 1997 has heightened attention on the FBA process; however, two challenges to the implementation of the functional approach must be addressed. First, the amendments do not give practitioners who are unfamiliar with the developmental history and research base of FBA specific information about what FBA is and what the FBA process looks like. Second, some individuals who might have a basic knowledge about the FBA process lack experience and fluency with the actual implementation process. They are inefficient and ineffective in (a) applying the FBA process to a full range of problem behaviors, (b) managing the process with a large number of students, (c) collecting and using data to assess and modify ineffective interventions, (d) teaching others about the process, (e) clarifying the difference between best practice and policy, (f) sustaining accurate implementation of the FBA process for and across individuals, or a combination of these.

To address and precorrect for these challenges, this article provides an overview of the FBA process. This article is organized around "frequently asked questions." Responses to the questions include general guidelines for completing the FBA process. Brief descriptions of the necessary components required to implement the FBA process within a school also are presented. Our focus is on completing the FBA. For information about building comprehensive behavior support plans, see Horner, Sugai, Todd, and Lewis-Palmer (1999–2000/this issue).

What is FBA?

Functional behavioral assessment is a systematic process for understanding problem behavior and the factors that contribute to its occurrence and maintenance (Horner, 1994; O'Neill et al., 1997; Repp, 1994; Sugai et al., 2000). More important, information collected during the FBA process serves as the basis for developing individualized and comprehensive behavior intervention plans (BIP). By identifying the behavior and the context in which the behavior occurs, the efficiency and effectiveness of the subsequent BIP is increased (Horner, 1994; O'Neill et al., 1997; Sugai, Horner, & Sprague, 1999; Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, & Hagan, 1998). The FBA process should be viewed as a problem-solving strategy that consists of problem identification, information collection and analysis, intervention planning, and monitoring and evaluation.

A major outcome of the FBA process is a summary or hypothesis statement that describes the problem behaviors and the factors that are believed to be associated with occurrence and nonoccurrence of the problem behavior. Thus, whenever FBA information is being collected, the goal of developing a summary statement always should be maintained and emphasized. A complete summary statement is composed of four key components: (a) identifying the problem behavior (e.g., verbal aggression, profanity, noncompliance), (b) triggering antecedents or events that predict when the behavior is likely to occur (e.g., request to complete difficult tasks, peer teasing), (c) maintaining consequences or events that increase the likelihood of the behavior happening in the future (e.g., avoid difficult tasks, gain peer attention), and (d) setting events or factors that make the problem behavior worse (e.g., lack of peer contact in previous 30 min, missed breakfast).

Accessing problem behaviors, triggering antecedents, and maintaining consequences is relatively easy (e.g., interviews, direct observations); however, the identification of setting events can be difficult. Setting events are circumstances or factors that make the problem behavior worse (more likely to occur or be more intense) by temporarily changing the value of typical consequence events. For example, when a student has a painful ear infection, the reinforcement value of verbal praise and high grades decreases, the corrective power of simple verbal reprimands decreases, and the value of avoiding adult attention increases. Other examples of setting events include fatigue, hunger, social conflict, routine change, academic failure, and so forth.

Why Do an FBA?

The primary purpose of completing an FBA is to enhance the effectiveness, efficiency, and relevance of BIPs (Horner, 1994; O'Neill etal., 1997; Repp, 1994; Sugai et al., 1999). The information collected and summarized during the FBA provides the basis for selecting specific and individualized strategies and supports for a student. More important, FBA information also guides the development of scripts and procedures for adults who will implement the BIP. Clearly, the impact of the BIP on student behavior is related directly to the accuracy with which the BIP is implemented.

Although FBA information can be collected in multiple ways (e.g., interviews, ratings, direct observation), it is essential to remember that the main reason we conduct FBAs is to improve our understanding of the problem behavior and guide the development of effective, efficient, and relevant BIPs. At present, we do not have the research base that enables us to use FBAs to determine directly (a) special education eligibility, (b) placement, or (c) whether a problem behavior is a manifestation of a disability. However, FBA information may be used to guide and inform regarding these decisions. For example, a change of placement might be recommended because the current environment lacks the supports and resources to implement the BIP.

Who Does an FBA?

As a process, the FBA is conducted by a team of individuals who have (a) direct experience with the student (e.g., teachers, family members, counselors); (b) behavioral expertise to lead the FBA process, collect FBA information, recommend strategies for the BIP, and so on (e.g., school psychologists, school counselors, special educators); and (c) administrative authority to support and make recommendations regarding personnel, resources, time, and so on. To the greatest degree possible, the student also should be involved.

At least one individual on the team must have the behavioral competence and expertise to lead the FBA process from problem identification, through information collection and analysis, to intervention implementation and monitoring. In addition, this person must have a working knowledge and fluency with the full range of BIP strategies for (a) minimizing, preventing, or neutralizing the impact of setting events; (b) removing antecedent events that trigger problem behavior and adding prompts that occasion appropriate behaviors; (c) teaching appropriate replacement behaviors (e.g., self-management, social skills, adaptive responses); and (d) removing consequent events that maintain problem behavior (e.g., extinction, DRO) and adding reinforcers that encourage appropriate behavior (e.g., positive reinforcement).

In sum, this individual is responsible for facilitating the team process, designing the assessment, summarizing the findings, and guiding the development of the support plan. Typically, the FBA process is led by school psychologists, school counselors, administrators, special educators, or a combination of these. However, any staff person can lead the process as long as he or she has the behavioral capacity and experience with the FBA process.

When Should an FBA Be Done?

From a "best" or "preferred" practices perspective, FBAs should be completed whenever a problem behavior is difficult to understand or a behavior intervention plan is needed to increase student success. Although the general FBA problem-solving process is basically the same across problem types, the intensity and complexity of individual FBA activities will vary; that is, not all problem behaviors and situations will require the same level of activity. For example, a teacher notices that every time Money makes noises in class, his peers tell him to be quiet, and then an argument occurs. Having seen Morrey engage in these behaviors a number of times, the teacher concludes that Morrey makes noises in class to access peer attention. Therefore, the teacher tells students to ignore Morrey's noises, teaches Morrey how to access peer attention in more appropriate ways, and provides positive reinforcers whenever he uses more appropriate behaviors. Basically, the teacher has assessed the situation from a functional perspective and has developed an intervention based on this assessment. In contrast, another teacher cannot figure out what triggers Leslie's temper tantrum episodes in which she throws her books, slaps her hands against the floors and walls, and screams out the windows; previous intervention attempts have produced little improvement. Therefore, to improve her understanding of the problem and modify the currently unsuccessful BIP, Leslie's teacher asks the school psychologist to interview Leslie; conduct direct observations in three periods each day for 2 days; review Leslie's educational file; and lead a BSP meeting with Leslie's dad, counselor, physical education teacher, and special education teacher. In both of these examples, problem behavior is identified, information is collected and analyzed, and an intervention is developed based on the assessment information. What varies is the intensity and complexity of the process.

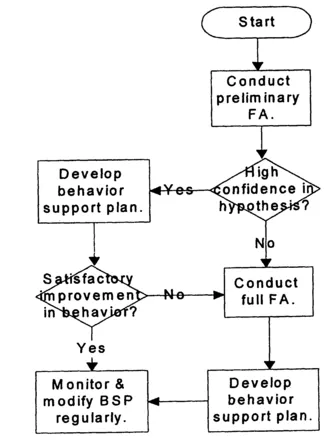

In general, a two-level FBA approach should be considered (see Figure 1). At the preliminary level, the objective is to collect the smallest amount of useful information that results in summary statements to which key individuals can agree and have high confidence about their accuracy. Information might be collected through brief interviews, archival review of discipline incidents, or informal direct observations. If high agreement and confidence is confirmed, then the next step is to develop and implement a behavior support plan based on that summary statement. If the plan is associated with acceptable outcomes, then the implementation and impact of the plan are monitored.

FIGURE 1 Overview of the functional behavior process. FA = functional assessment; BSP = behavior support planning.

If, however, individuals do not agree with the summary statements, or lack confidence in the accuracy of the statements, the second level consists of a full FBA. Unlike the first level where information collection was informal and less intense, a team might recommend more than one type of interview (e.g., teacher, student, parent), a more thorough archival review (e.g., previous intervention plans), more formal direct observations across multiple settings (where problem behavior occurs and does not occur), or a combination of these. The additional information collected through full FBAs would be used to clarify, refine, or develop new summary statements, BIPs, or both. As with preliminary FBAs, the objective of full FBA would be to establish agreement and confidence in summary statements and develop or modify BIPs that are more likely to be effective, efficient, and relevant.

Both levels of assessment result in complete hypothesis statements and behavior support plans. They differ in the amount of information that is collected and the intensity of the assessment strategies. The general rule is that the intensity of the assessment should be matched to intensity of the problem behavior.

What is Required to Support and Sustain the Effective and Efficient Use of FBA in Schools?

Simply having an individual within the school who has the behavioral knowledge and competence to complete and develop FBA-based BIPs is necessary but insufficient. For the FBA process to be efficient, effective, and sustained, a school environment must be established that supports all school staff in their implementation efforts. FBA-based BSP is part of a continuum of support that begins with school-wide and classroom management systems for all students, staff, and settings to specialized group-based and individualized interventions for students who display significant problem behavior. Several key components are necessary for a school to establish a full cont...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Preface

- Articles