This is a test

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

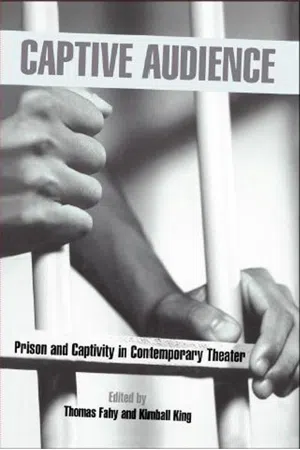

The first collection on this important topic, Captive Audience examines the social, gendered, ethnic, and cultural problems of incarceration as explored in contemporary theatre. Beginning with an essay by Harold Pinter, the original contributions discuss work including Harold Pinter's screenplays for The Handmaid's Tale and The Trial, Theatrical Prison Projects and Marat/Sade. Kimball King, Thomas Fahy, Rena Fraden, Tiffany Ana Lopez, Fiona Mills, Harold Pinter, Ann C. Hall, Christopher C. Hudgins, Pamela Cooper, Robert F. Gross, Claudia Barnett, Lois Gordon

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Captive Audience by Thomas Fahy,Kimball King in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

1

The Confessional Voice: Medea's Brutal Imagination

RENA FRADEN

Indeed there is a dialectic at the heart of the scene of crime—a surplus and a simultaneous dearth of meaning. Looking at the scene of crime we experience an overwhelming presence of meaning, but a sense also of the evanescent, banal, insubstantial.

—PEARSON AND SHANKS

The confession has spread its effects far and wide. It plays a part in justice, medicine, education, family relationships, and love relations, in the most ordinary affairs of everyday life, and in the most solemn rites; one confesses one's crimes, one's sins, one's thoughts and desires, one's illnesses and troubles; one goes about telling, with the greatest precision, whatever is most difficult to tell…. One confesses —or is forced to confess. When it is not spontaneous or dictated by some internal imperative, the confession is wrung from a person by violence or threat; it is driven from its hiding place in the soul, or extracted from the body.

—MICHEL FOUCAULT

The first time I heard the director of the Medea Project in San Francisco, Rhodessa Jones, describe how she conducted workshops in jails with incarcerated women, forcing them to see the ways in which they had been abused by men, while their own rage had caused them to abandon their children, I was struck by how brilliantly that classical reference highlighted similarities and differences in their stories. The women in the 1990s were held hostage to men and to drugs, trapped in a victim/victimizer's vicious circle, angry, like the classical Medea, but without any of her skills—her spells and connections to gods and her gift for plotting. It may be enough to remind ourselves briefly that Euripides's Medea never apologizes and never confesses, nor does she ever express guilt. She hesitates, but then she steels herself to be a hero, sends her children off to murder the woman who is to become her husband's new wife, and then moves offstage to kill her own children to punish her husband for deserting her. Euripides might give us cause to think of her as monstrous by the end of his play, and perhaps she is a monster because she feels no remorse. I am not sure. In Greek tragedy, the violence mostly happens offstage, while the stage becomes the place to make sense of it; there are explanations, though usually not repentance. One of the biggest differences between the classical theater and the modern reenactment of the Medea plot, it has come to seem to me, is the striking absence and then necessary presence of confession. It is easy to forget that Euripides's Medea, in the end, escapes many possible punitive endings, including a definitive social judgment against her. She is not put to death or even imprisoned, but flies off in the sun god's chariot, off to Athens and the future— in which god only knows what she'll do next. Modern Medeas are not such good escape artists. We have trapped them, forced them to confess, to feel guilt, to explain themselves, to seek penance, to say they were crazy, to justify themselves in some way, to seek our forgiveness and our understanding. But the confession weirdly contains something of that dialectic noted above: an overwhelming sense that the confession should mean so much and do so much, and an uneasy sense that the confession is never commensurate with the crime.

In my book, Imagining Medea: Rhodessa Jones and the Theater for Incarcerated Women, I described a theatrical project that relies principally on exposing the stories of people's lives. The Medea Project works with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women in the San Francisco jails, shaping their life stories around myths and music and dance, and performing in public for a limited run, with permission from the sheriff to do so. It can be seen as both postmodern in its juxtaposition of styles, of hip-hop and African drumming, of stilt walkers and trapeze artists, of Greek and African myths, and as humanistic in an old-fashioned sense, believing in the free will and the accessibility of truth, the usefulness of expressing the self. In each performance, at certain moments, the swirl of busy dances and musical numbers subsides, and a woman steps forward to deliver a speech, which is both confessional and autobiographical. This moment, in stark contrast to the busy dances and musical numbers, is unadorned and quiet, but also more powerfully arresting, as the movement, literally, stops. It appears dramatically as a separation. The woman, no longer part of the mass group or chorus, breaks free to claim her own space, speak in her own voice, becoming the dramatic equivalent of a slar, in the spotlight, featured, an individual, someone we must notice. And how we read this is unmistakable. It is a dramatic moment that proclaims: “This Is the Truth,” their truth, her truth, a revelation, a confession.

Much of what drives the Medea Project is the belief in the necessity for a shared confessional moment. Rhodessa Jones, the director of the project, believes that people can't “move on” with their lives until they confront their past and speak it publicly. The confessional moment drives both the workshop and the arc of the public performance. In it, the women reimagine themselves, looking backward and then casting forward. Many of the people involved in the Medea Project—including the sheriff, the guards, and the women themselves— believe that the act of confession is therapeutic, part of the rehabilitation process. A common-sense response is to say, “Of course.” Imagining Medea contains a healthy chunk of interviews from all the participants. I depended on the interviews for my “evidence” as to how the project worked. But I spent very little time interrogating the interviewees' conceptions of their confessions or analyzing the material the interviewees produced. I didn't press people on gaps in their stories, as I might have if these were purely texts or dead people. Partly this was because I felt honor bound to “believe” them, and partly, I felt the main point of the book was to describe how the participants felt they were participating. At the same time, it seemed to me, the more I came to know something about some of the women and the way the project developed, the more complicated and vexed that confessional moment became for me.

Most everyone involved in the project knew that to tell the Medea Project only as an upbeat story of salvation and liberation would not do justice to other plots. The number of women participating over ten years was still very, very small (maybe one hundred of the thousands of women committed in increasing numbers in the jails of San Francisco alone). And many of the women disappeared completely, so it was impossible to know what happened to them next. On the one hand, the power of that confessional moment in workshop and performance, in which the women tried to express not only the shape of the particular crime that landed them in jail, but also their newly created, different, saved self, always elicited the cheers and laughter and hopefulness from spectators, and from me as well. But on the other hand, neither the art of the sort they were involved with in the Medea Project (composing songs, dancing, reenacting myths), nor those confessional revelatory moments performed in workshops and then on stage could ensure literal or figurative freedom from old selves, that they would be sprung, no longer imprisoned or held captive to old stories, bad plots. An ongoing balancing act marked the project between the optimism of the confession and pledge to be different and the skepticism that a confession, even if truly felt, could perform the necessary liberation from horrendous surroundings. Increasingly I came to feel that the one confessional moment was somehow not equal to the complexity of a life—not false exactly, but certainly only partial—and I became suspicious that confessions did not always lead back, whatever the truth status of the confession, to power and liberation.

It wasn't at all the truth of a particular confession I was questioning; I was just trying to figure out what work the confession was supposed to do. There is already a way in which the theater contaminates or at least complicates the parameters of sincerity and authenticity, even in a project that depends upon a certain amount of autobiographical transparency. When a soliloquy, for instance, promises to reveal to us a character's true thoughts and real self, it can only do so because of the contrast between the performance the character puts on for others and the performance about to be put on for us. The character is always performing for an audience; the audience changes and the form of address may change as well, but a character is never not performing versions of the self to others in the theater. They may be said to have designs on us—the audience—as much, if not more, than the adversaries they face on stage. The rhetorical space of the theater, like that of the confession, depends upon a relationship between at least two people: a participant (the confessor, the actor) and a spectator (the person who hears the confession, the audience).1 Theater, like the confession, must occur in a social space. But what sort of transaction takes place there? How does the theatrical social space with its particular generic conventions shape the work that confession is supposed to do? Who was I as a spectator hearing these confessions? If my role was to absolve and forgive, as a priest would, how literally was I supposed to do this? Or was I in the position of interrogator, an implicit prosecutor? Did my desire to hear confessions, to believe in them, and be swept away by them, drive the production of them? And why did I so want to hear them?

Obviously, Foucault's genealogy of confession has helped to confirm my sense that confessions are a historical development, not natural human behavior. (The Catholic Church doesn't deem the confession a sacrament until the thirteenth century, for instance.)2 We are now, at least in Western culture, what Foucault calls a “confessing animal” (Foucault 59). Whether coerced or spontaneous, confessions are driven from hiding so that every aspect of our life seems revealed to the panoptic gaze. But what is important to Foucault is the way in which the confession is a ritual that exists within a power relationship. I quote at length:

Whence a metamorphosis in literature: we have passed from a pleasure to be recounted and heard, centering on the heroic or marvelous narration of “trials” of bravery or sainthood, to a literature ordered according to the infinite task of extracting from the depths of oneself, in between the words, a truth which the very form of the confession holds out like a shimmering mirage. Whence too this new way of philosophizing: seeking the fundamental relation to the true, not simply in oneself—in some forgotten knowledge, or in a certain primal trace—but in the self-examination that yields, through a multitude of fleeting impressions, the basic certainties of consciousness. The obligation to confess is now relayed through so many different points, is so deeply ingrained in us, that we no longer perceive it as the effect of a power that constrains us; on the contrary, it seems to us that truth, lodged in our most secret nature, “demands” only to surface; that if it fails to do so, this is because a constraint holds it in place, the violence of a power weighs it down, and it can finally be articulated only at the price of a kind of liberation. Confession frees, but power reduces one to silence; truth does not belong to the order of power, but shares an original affinity with freedom: traditional themes in philosophy, which a “political history of truth” would have to overturn by showing that truth is not by nature free—nor error servile—but that its production is thoroughly imbued with relations of power. The confession is an example of this….

The confession is a ritual of discourse in which the speaking subject is also the subject of the statement; it is also a ritual that unfolds within a power relationship, for one does not confess without the presence (or virtual presence) of a partner who is not simply the interlocutor but the authority who requires the confession, prescribes and appreciates it, and intervenes in order to judge, punish, forgive, console, and reconcile; a ritual in which the truth is corroborated by the obstacles and resistances it has had to surmount in order to be formulated; and finally, a ritual in which the expression alone, independently of its external consequences, produces intrinsic modifications in the person who articulates it: it exonerates, redeems, and purifies him; it unburdens him of his wrongs, liberates him, and promises him salvation. (Foucault 59–60, 61–62)

Foucault calls attention to two things that seem important to me. One is recognizable: that classical literature is short on confession and that we no longer delight as much in heroic trials as we do in narratives that describe the interior of the heart. But I underscore Foucault's description of modern literature in which the truth of the self becomes a “shimmering mirage”; the truthful self seems to be there, but it isn't really, first because it is an infinite task, this extracting from the depths of oneself the truth of oneself, and second because the truth does not seem to lie in words but rather in between the words, so that the form of the confession, which is necessarily in words, is not equal to the task. The second proposition makes strange what seems common sense: Confessions may not be (only) sources of truth; even when they are taken to be true, truth is never free from the effects of power: “[T]ruth is not by nature free—nor error servile….” Modern Medeas are good case studies of the theatrical problematics of the confession: Their extreme crimes strain the descriptive capability of language, and the crimes themselves turn on the exercise of power and the effect of having none.

One of the modern Medeas who was invoked in the Medea Project's fourth production, Buried Fire, in 1996, and who appeared as a character in Cornelius Eady's play, Brutal Imagination, in 2001–2002, was the historical Susan Smith. In 1994 Smith claimed that she and her children were kidnapped by a black man, only to confess nine days later that she had herself released the emergency brake of her car with her children strapped in their car seats and let it roll into John D.Long Lake in South Carolina. Her handwritten confession, which was published in newspapers, only describes her state of mind the evening she killed her children. It does not give any sort of a back story, no family genealogy. On the one hand, it is very satisfy ing to be able to read a confession so neatly and definitively delivered. Nine-day my stery solved. Responsibility taken. No loose ends. But on the other hand, the text of this confession is astonishingly clichéd and banal, and Smith is so quick to assign herself forgiveness that it risks our incredulity. What follows is the complete confession:

When I left my home on Tuesday, Oct. 25, I was very emotionally distraught. I didn't want to live anymore! I felt like things could never get any worse. When I left home, I was going to ride around a little while and then go to my mom's. As I rode and rode and rode, I felt even more anxiety coming upon me about not wanting to live. I felt I couldn't be a good mom anymore, but I didn't want my children to grow up without a mom. I felt I had to end our lives to protect us from any grief or harm. I had never felt so lonely and so sad in my entire life. I was in love with someone very much, but he didn't love me and never would. I had a very difficult time accepting that. But I had hurt him very much, and I could see why he could never love me. When I was at John D.Long Lake, I had never felt so scared and unsure as I did then. I wanted to end my life so bad and was in my car ready to go down that ramp into the water, and I did go part way, but I stopped. I went again and stopped. I then got out of the car and stood by the car a nervous wreck. Why was I feeling this way? Why was everything so bad in my life? I had no answers to these questions. I dropped to the lowest point when I allowed my children to go down that ramp into the water without me. I took off running and screaming, “Oh God! Oh God, no!” What have I done? Why did you let this happen? I wanted to turn around so bad and go back, but I knew it was too late. I was an absolute mental case! I couldn't believe what I had done. I love my children with all my (a picture of a heart). That will never change. I have prayed to them for forgiveness and hope that they will find it in their (a picture of a heart) to forgive me. I never meant to hurt them!! I am sorry for what has happened and I know that I need some help. I don't think I will ever be able to fo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- General Editor's Note

- Captive Audience: An Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Contributors