eBook - ePub

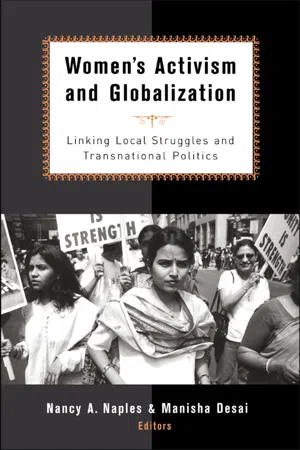

Women's Activism and Globalization

Linking Local Struggles and Global Politics

This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women's Activism and Globalization

Linking Local Struggles and Global Politics

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Women's Activism and Globalization is a broad and comprehensive collection that shows how women activists across the globe are responding to the forces of the new world order in their communities. The first person accounts and regional case studies provide a truly global view of women working in their communities for change. The essays examine women in urban, rural, and suburban locations around the world to provide a rich understanding of the common themes as well as significant divergences among women activists in different parts of the world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Women's Activism and Globalization by Nancy A. Naples, Manisha Desai in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

Organizing across Borders

4

Women to Women

Dissident Citizen Diplomacy in Nicaragua

Clare Weber

THE WISCONSIN COORDINATING COUNCIL ON NICARAGUA (WCCN) WAS PART OF an historic social movement in the United States that aimed to end U.S. military intervention in Central America and, in particular, Nicaragua. In the 1990s, the organization shifted its transnational activist strategies to challenge the gendered and racialized effects of global economic restructuring in Nicaragua. To this end, the WCCN worked with the Nicaraguan March 8 Women’s Inter-collective on projects to end violence against women and with the Coalition of Protestant Churches for Aid and Development (CEPAD) to establish a loan fund. Viewing this reconfiguration from a multicultural, multiracial feminist standpoint, I explore how the WCCN developed a series of projects with Nicaraguan nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that aimed to address the social and economic injustices of global economic restructuring in Nicaragua. The study demonstrates that, even as the WCCN worked to reverse the North-to-South flow of ideas and development strategies, the organization and its Nicaraguan counterparts were circumscribed in locally specific ways by the very power imbalances they were attempting to undo.

Third World feminist scholars have criticized First World feminist scholarship and activist strategies for viewing Third World women through a Westernized lens, assuming that individuality and modernity would be liberating forces for Third World women (Grewal and Kaplan 1994; C.Kaplan 1997; Mohanty 1991b). Women, viewed through this hegemonic lens, lose agency. International conferences and United Nations-sponsored projects have both perpetuated and challenged this hegemonic form of global feminism (Meyer and Prügl 1999). In their work on transnational activist networks, Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink state that contemporary transnational activism does not always fit the much-criticized North-to-south pattern of international nongovernmental organizations transmitting liberal Western values to less powerful activists in the South. Rather, “many networks have been sites of cultural and political negotiation rather than mere enactors of dominant Western norms” (1998a). Keck and Sikkink do not offer a specific gendered analysis of transnational activist networks. Newer research in this area, as exemplified in this book, examines women’s activist challenges to globalization in a transnational context.

Building on U.S. Third World feminist scholarship (Hurtado 1996; Sandoval 1991; Zinn and Dill 1996), Nancy Naples and Mamie Dobson (2000) view feminist praxis as “a grassroots strategy and an ongoing achievement based in the philosophy and practice of participatory democracy and situated knowledges” (3). I use this definition of feminist praxis to illustrate how a predominantly Euro-American progressive organization, a Nicaraguan feminist NGO, and a Nicaraguan church-based development organization advanced a strategy of exchange and activism aimed at challenging the gendered and racialized effects of global economic restructuring in Nicaragua.

The WCCN emerged as a left progressive organization opposed to the U.S. policies toward the socialist government of the Nicaraguan Sandinista Party. The WCCN referred to its activist strategies, which I discuss below, as citizen diplomacy. Drawing on the work of Holloway Sparks (1997), I refer to this idea of citizen diplomacy as dissident citizen diplomacy. While Sparks’s work focuses on marginalized activist women in the United States, her concept of dissident citizenship is appropriate for the purposes of this study in that it highlights the “noninstitutionalized practices that augment or replace institutionalized channels of democratic opposition when those channels are inadequate or unavailable” (83). Dissident citizen diplomacy and multicultural feminist praxis enabled the WCCN to challenge, in gendered ways, the hegemonic powers that first waged a counterrevolutionary war against Nicaragua’s socialist government and then imposed neoliberal economic policies favorable to international capital.

Nicaraguan Revolutionary Activism

Nicaragua underwent tremendous social, political, and economic transformations in the latter part of the twentieth century. It received intense international scrutiny, as well as support, when the Sandinista guerrilla movement overthrew the Somoza dictatorship on July 17, 1979. The Sandinistas, in the early years of their government, established a form of participatory democracy that gave formal power to a myriad of grassroots organizations (Hoyt 1997; Quandt 1995; Ramée and Polakoff 1997). The government implemented social programs to decrease poverty, expand social security, and increase access to land, housing, health care, education, and basic provisions. As part of a mixed economy, the majority of production stayed in private hands. Nevertheless, peasant farmers had greater access to land in the form of state farms, cooperatives, and some individual titles. Food production for domestic consumption increased significantly.

Nicaraguan women had the most to gain from the improved social conditions of the revolution, given their disproportionate responsibility for household and for community caretaking. Additionally, the government, at the urging of the Sandinista-affiliated Nicaraguan women’s association Luisa Amanda Espinoza, passed laws in favor of women’s rights, such as the right to have wages garnered for child support. However, the government also pushed women into the formal labor market and encouraged them to participate in the party, grassroots organizations, and cooperatives. In effect, this increased women’s work adding onto their responsibilities as mothers, housewives, and single heads of households. Furthermore, feminist concerns of patriarchy and male privilege within the household were overlooked by the Sandinista Party (Chinchilla 1995; Molyneux 1986; Randall 1992).

Nicaraguan women’s attempts to advance a feminist agenda were further thwarted when Ronald Reagan, elected U.S. president in 1980, made it his personal cause to overthrow the Sandinista government. The Reagan administration gave military support to counterrevolutionary forces living in exile, pressured the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank to cut off all economic aid and loans and began an impressive propaganda campaign to internationally discredit the Sandinistas (Burns 1987; Walker 1997). Applying many of the lessons learned from the Vietnam War, the CIA recruited, trained, and supported counterrevolutionary forces in a strategy of low- intensity warfare designed to wage war without the use of U.S. troops. By the end of the Contra War, 30,000 of Nicaragua’s total population of 4 million had been killed, and more than $12 billion in damage had been done (Kornbluh 1987; Prevost 1997).

Because the low-intensity warfare strategy avoided the use of U.S. troops, it also avoided an anti-interventionist movement like that which emerged during the Vietnam War (Kornbluh 1987). Despite attempts by the U.S. government to avoid popular opposition to its involvement with the war in Nicaragua, an anti-intervention movement did emerge to mobilize public opinion against the war. The movement pressured the U.S. Congress to end military support for the Contras, but the Reagan administration simply resorted to illegal means to fund them. While not stopping the Contra War, movement activists generally concur that they successfully prevented an outright invasion of Nicaragua by U.S. troops.

While Nicaragua successfully garnered international support against U.S. policy, the Reagan administration effectively undermined many of the aims of the revolution. The last five years of the Sandinista government saw deterioration in an economy that had previously been growing. The power granted the grassroots organizations was diminished by a transition to electoral representation and the use of these organizations to carry out top-down Sandinista policies in the face of a worsening economy and the shifting of resources from social welfare to war (Walker 1997). Popular support for the Sandinistas, after nearly 10 years of war, had diminished. In 1990, the Sandinistas were voted out of office and replaced by the U.S.-supported United Nicaraguan Opposition (UNO).

Nicaragua-U.S. Relations in the 1990s

The 1990 electoral victory of UNO paved the way for the United States to direct Nicaragua’s economic policies. The White House had a ruling party that would willingly restructure Nicaragua’s government and economy to serve the interests of international capital. While the Sandinistas fell short of the revolutionary goal of undoing gender inequality, the Chamorro government actively targeted women’s issues from a conservative agenda (Metoyer 1997).

The UNO government’s imposition of neoliberal economic policies, as dictated by the U.S. State Department, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), began undermining the social and economic gains of the Nicaraguan revolution. These policies continued after the Liberal Party won elections in 1996. The neoliberal economic policies now in place in Nicaragua and many other countries and regions of the world shift the burden of social services away from the state and onto women, relying on their unpaid labor as mothers, homemakers, or single heads of households (Benería 1996).

In 1990s Nicaragua, neoliberal policies in the form of structural adjustment programs (see Desai in this volume) compromised food security, increased unemployment, threatened land tenure for poor rural and urban Nicaraguans, limited access to credit for small producers, and cut state support for health care and education. International peace and justice organizations like the WCCN faced a worsening economic situation in Nicaragua and a government that was anything but friendly. In addition, U.S. grassroots support for work in Nicaragua waned once the war ended. Nevertheless, 10 years of revolutionary government left a legacy of a politically mobilized population and a network of international solidarity. Both would play key roles in shaping activist challenges to global economic restructuring.

U.S.-Nicaragua Activist Allies

The WCCN was created in 1984 by the citizens of Wisconsin in response to a disagreement with the Wisconsin Partners of the Americas regarding its sister city relationship with Nicaragua.1 Left progressive citizens of Wisconsin disagreed with the Partners position of not opposing President Reagan’s policies toward the Sandinista government. Friends in Deed (Chilsen and Rampton 1988), a how-to of sister city projects published by the WCCN, developed the notion of citizen-to-citizen diplomacy from an activist manual titled “Having International Affairs Your Way: A Five Step Briefing Manual for Citizen Diplomats”:

So, you want to become a diplomat? Welcome aboard! You’re about to join the ranks of thousands of Americans who’ve decided that diplomacy is too important to be left to the diplomats. It’s a big step, a step that may well change your life. But it’s also a step that will enrich your life and the lives of many others. Diplomacy is essentially the art of helping the world. (Shuman and Williams 1986, 3)

Motivated by ideals of social and economic justice, Wisconsin citizens effectively used the model of Partners of the Americas to establish an alternative foreign policy merging activist challenges in the United States and development aid in the form of nationwide sister city projects. The projects supported Nicaraguan communities’ efforts to build schools and housing, dig wells, and take on other social and economic projects in agreement with the aims of the revolution.

In Nicaragua, many Sandinista activists who were once part of the revolutionary government organized grassroots NGOs to challenge the neoliberal economic policies of the UNO and, later, Liberal Party governments. These organizations drew on members’ 10 years of experience in revolutionary organizing and grassroots participation to challenge the neoliberal government’s attempts to dismantle the social, material, and political gains of the revolution. In addition, these grassroots NGOs drew on international contacts and networks formed during the war years when international solidarity with Nicaragua was strong.

The Nicaraguan women’s movement is particularly significant to the growth of NGOs and community activism in Nicaragua. Many women working within the Sandinista Party and government formed NGOs independent of the party with the aim of addressing women’s issues regardless of the Sandinista Party’s policies on any given women’s issue. The women’s movement incorporated a broad spectrum of concerns, such as violence against women and legal, health, labor, and abortion rights. The woman-headed household as an economic unit positioned women as ultimately responsible for meeting the needs of the family (Benería 1996). This economic responsibility, coupled with the collective experience of feminist activism during the revolution, led many women to organize on behalf of their communities (Aguilar et al. 1997).

In the 1990s, the WCCN would connect with the March 8 Women’s Inter- collective and CEPAD, one of the oldest and largest NGOs in Nicaragua. The process and the emergence of the WCCN s activist strategies are grounded not only in the organization’s history, but by a multicultural feminist praxis. This approach was represented in the organization’s goal of equal exchange of ideas and, potentially, resources. The development and issues of the WCCN s Women’s Empowerment Project and the Nicaraguan Loan Fund represent transnational activist responses to economic restructuring in Nicaragua that are worked out in a local context, often contested and almost always dynamic.

In the postwar 1990s, the WCCN offered alternatives to the neoliberal economic policies meted out by the government. A WCCN activist said of the organization’s economic initiatives,

It’s a way of coming to terms with the market system. If things are going in the direction of the victory of big-time capitalism or maybe small-time capitalism, we’ll be a help. Maybe there’s a way for this idealism and this desire for justice to work itself out in this quite different political circumstance once the Sandinistas were beat in the election.

When the Sandinistas lost power in Nicaragua, many U.S. activists involved in the antiintervention strategies saw the electoral defeat as a victory for international capital. Activists then had to grapple with how to address U.S. policy in its newest form. Building on the relationships of international solidarity and activist experiences in Nicaragua, the WCCN continued challenging global economic restructuring in local and grassroots ways.

Maintaining a commitment to social justice in Nicaragua meant that the WCCN had to transform itself. The WCCN was one of a number of organizations that worked to understand the significance of global economic restructuring in a grounded and con- textualized manner; it asked itself how this restructuring affected people’s daily lives in Nicaragua. Through feminist praxis, the WCCN not only critiqued the harsh gendered and racialized effects of neoliberal economic policies, but developed strategies that responded to needs in Nicaragua while continuing financial and political support for the organization in the United States. A member of the WCCN’s Women’s Empowerment Committee said,

Now we’re focused on different economic models-both through the loan fund and through the Women’s Empowerment Project. So it’s focused on alternatives to what already exists. You know, it attracts people who want to live some of those alternatives.

The Women’s Empowerment Project

In this section I demonstrate how the WCCN, through multicultural feminist praxis, centered women’s issues in 1990s Nicaragua, effectively inserting a feminist agenda into dissident citizen diplomacy. Prior to the Women’s Empowerment Project, dissident citizen diplomacy served as a tool to organize against U.S. military and economic aggression in Nicaragua. The 1990s emphasis on women’s issues signified a shift from the antiwar politics of the 1980s. Dissident citizen diplomacy represented a feminist, proactive strategy intended to serve as an alternative model to U.S. economic and political hegemony in Nicaragua. However, this does not mean that the WCCN did not pursue political actions of opposition in the United States.

From the outset the WCCN women who formed the Women’s Empowerment Project engaged in a grassroots strategy of participatory and democratic decision making, all the while trying to educate themselves on the situated and lived realities of Nicaraguan activist women. They were clear that they wanted an exchange of information and as equal a relationship as possible. One member of the Women’s Empowerment Project gave the account of the group’s early days:

One of the things that was initially really important in really making things happen was getting a core group of women together and saying, “We need to really think about what the objectives are, we need to think about what the mission is, we need to think about what it is that we can do, how we can share information, how we can continue to communicate in a way that’s egalitarian in which both parties are learning...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- I: Introduction

- II: Organizing across Borders

- III: Localizing Global Politics

- IV: Activism in and against the Transnational State

- V: Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Contributors