Introduction

This book is designed to demonstrate the interconnections between the housing stock and households. The focus is on understanding the demand for housing and the way in which the demand is fulfilled as households select housing. This book is concerned with both the decision to move one’s residence and the resulting type of housing choice. The housing supply—the stock of dwellings—is the context within which households make choices and acquire housing.

Residential relocation is the household decision that generates housing consumption changes, which ultimately changes the residential mosaic. It is not merely a decision about changing locations; it is also a decision about tenure—about whether to own or to rent. Although relocation can be within the same tenure, the concept that has dominated research into housing markets is the process of changing from renting to owning, as most countries in the Western world have moved from predominantly rental societies to societies of homeowners. Thus, tenure choice will be central to the analysis in this book. It does, however, discuss the residential relocation decision as the impetus for housing choice. In this sense, the aims of the presentation are circumscribed to an effective discussion of how households are distributed within the housing system and what influences their choices.

The process of “matching” households and houses is examined in this book in two very dissimilar housing markets—the United States and the Netherlands. There are at least two reasons why it is both revealing and useful to view the process of housing choice against the background of two nations with dissimilar housing histories and differing tenure structures. First, it demonstrates that regularities in mobility and tenure choice are present and hold up in both national contexts. This suggests a robustness in models of the matching process of households and housing which is central to the discussion in chapters 3 through 5. Despite differences in social context, in policy intervention and in “housing culture,” the generalized choice processes operate similarly. Second, and conversely, there are important differences in the outcomes of the matching process of households and housing in the United States and the Netherlands, as will be illustrated in chapter 6. One can demonstrate that the nature of the Dutch housing system has “cushioned” some of the recent housing problems of homelessness, inner-city decay, and overcrowding, which have reemerged in Western societies.

There are also some pragmatic reasons for comparing the process of housing choice in the United States and the Netherlands, such as the availability of excellent data at the household level in the Netherlands. This data covers substantial periods of housing market fluctuations, and the authors have worked with this material for the last decade. The decision to analyze the mobility process against these two backgrounds, however, also relates to a debate that has emerged in the last few years on the relative roles of both market forces and government regulations in the housing market.

Some scholars, mostly in the United States where government regulation of housing is relatively limited, suggest that market mechanisms can efficiently allocate housing, and that housing markets respond to the effective demand of consumers (Nesslein 1988). Rising real incomes will create an increased supply of good housing, and the cost of new construction is much lower if the government does not hamper the process. As a corollary, Nesslein argues that the welfare state arrangements, which were designed to expand the supply of good shelter for the entire population, may have lowered, rather than increased, the level of housing investment.

Other scholars, mostly from Western Europe where government intervention in housing has flourished during the long period of rising incomes and expectations from 1950 to 1980, hold that the housing commodity cannot be allocated efficiently, and certainly not fairly, without government intervention in the market process. In this view, market forces result in an unattractive rental sector, urban slums, and housing polarization (Ambrose 1992). Kleinman (1995) argues that in France and Britain, where housing policy took an explicit turn toward the market during the late 1970s and 1980s, this has indeed led to a situation in which housing needs are left unmet and housing is in increasingly short supply.

This is not the place to take a position in this debate. This book is not about housing policy and policy outcomes but, rather, about the behavior of people in the housing market. Yet, it is a fact that throughout Western Europe, government regulation exists and influences both construction and demand for housing. In this book, the Netherlands presents an example of the regulated housing markets of Western Europe. Actually, even among the countries of Western Europe, the Netherlands is remarkable for the magnitude of government regulation and its extremely large social (public) rented housing sector. It is, therefore, a good housing market to contrast with the relatively free housing market of the United States.

Chapter 2 presents the theoretical notions about the character of the housing stock, the mobility process over the life course, and the way in which mobility and housing choices are interlinked. The following three chapters elaborate on the way individuals and households, with particular age and income characteristics, relocate within particular housing markets and what influences their choices. We also demonstrate that both national and local social and economic contexts do affect the final form of the outcomes. Chapter 6 examines the aggregation of individual actions into general outcomes in the residential mosaic. Before beginning a discussion of the processes of mobility and housing selection, however, it is very important to have a clear idea of the aggregate context within which the choices are being made, which is the intention of chapter 1.

This first chapter is designed to illustrate the overall structure of the housing markets in the United States and the Netherlands. It begins with a historical review of the development of homeownership, because the move from rental housing to homeownership is one of the most salient trends in Western societies during this century. Not all societies have moved in this direction at the same pace, however. This is partly owing to housing market regulation, although the rate of increase in real income is also a factor. As will be demonstrated, the United States is among those countries that have rapidly and dramatically become nations of homeowners, while the Netherlands is an example of nations that are still predominantly renter societies.

In addition to tenure, this discussion of the nature of the housing stock within which choices must be made is limited to the type of dwellings, the price and value of housing, and the geographical location of housing within metropolitan areas. The wide range of characteristics of the stock remains intentionally unexamined because, as will be demonstrated—apart from tenure—type, price, and location are the major points households consider when moving from one dwelling to another. They are also the main characteristics considered in the examination of outcomes of housing choice in chapter 6.

The Historical Context of Homeownership

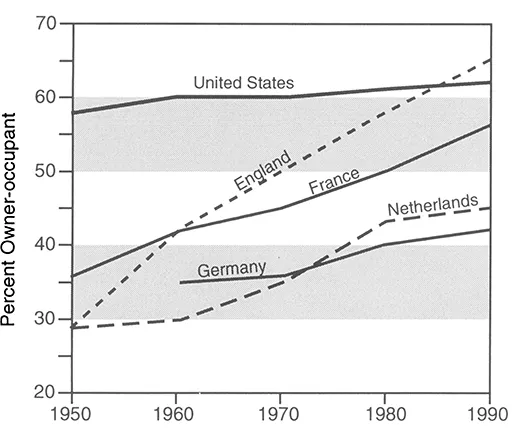

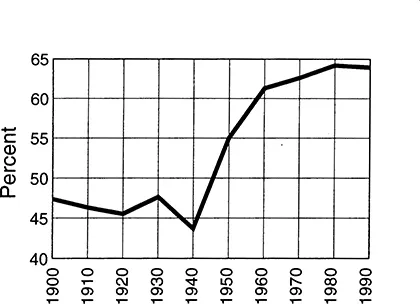

In the majority of Western economies, the role of private rental housing has contracted dramatically (Power 1993). Notwithstanding, during the 1990s there is still considerable variation in ownership rates, and the trajectories in the homeownership rate vary considerably (fig. 1.1). The United States is one extreme of a nation of predominantly homeowning households and has been such for much of the past four decades. But the United States was not always a nation of homeowners (fig. 1.2). The change came after World War II. The ownership rate had hovered in the 45 percent to 47 percent range for most of the first half century but, beginning in 1945 (the Census year is actually 1940 although the real change began after World War II ended), the rate of ownership increased steadily in each decade. It has stabilized in the last ten years at about 64 percent.

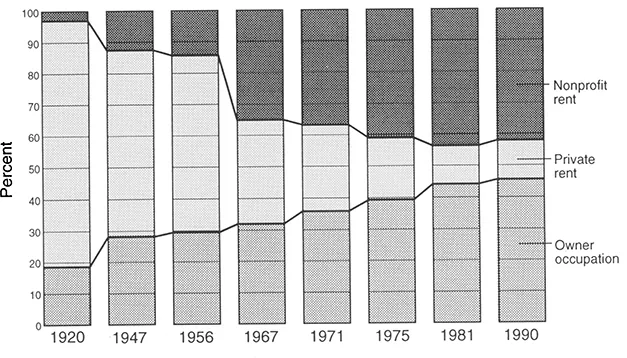

Many countries in Western Europe, such as the United Kingdom and France, have also had relatively rapid increases in the proportion of homeowners; they are now approaching the United States in the proportion of dwellings that are owned (fig. 1.1). In other countries, such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland, rental housing is still the largest single part of the stock. It is, however, split differently in various countries between private and nonprofit sectors of the market. In Germany, private rent still remains the largest single tenure (38 percent), while in the Netherlands the role of private rental housing declined after World War II (fig. 1.3). The Dutch government pursued a policy of mass provision of nonprofit rental housing, which, in the 1960s and 1970s, made this the largest tenure in this country (Harloe 1995). Now homeownership is the largest single sector of the market. It is greater than either private rental or public rental but not larger than these two sectors combined. Thus, most Dutch households are still in the rental sector (Dieleman and Everaers 1994). The same situation can be observed in Germany, where 40 percent of households are owners, and the majority rent a private or subsidized housing unit in the public rental sector.

FIGURE 1.1

Development of the homeownership sector in five Western countries from about 1950 to 1990

Source: Elsinga, 1995. Redrawn by permission of Delft University Press.

FIGURE 1.2

Owner-occupied units in the United States

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1990 Census Housing Highlights CH-S-1-1, 1991.

FIGURE 1.3

Development of housing tenures in the Netherlands, 1920-1990

Source: Adapted from Hoekveld et al., 1984.

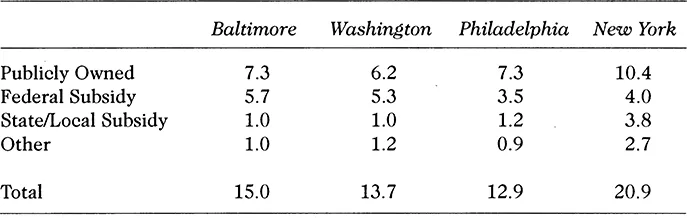

Unlike many European countries, and the Netherlands in particular, the United States has eschewed any serious commitment to a subsidized housing program. There are, however, almost five million housing units that are publicly owned or that have some form of federal, state, or local subsidy. This constitutes approximately 4 percent of the U.S. housing stock in comparison with 40 percent of the housing stock in the Netherlands. Most subsidized housing is located in the central cities, but more than a million units of subsidized housing are in suburban and nonmetropolitan areas. Although the proportion of publicly owned and subsidized housing is low for the United States as a whole, in some cities the proportion is closer to that of some European countries. Almost 21 percent of the rental stock is publicly owned or subsidized in New York City, and the proportion varies around the mid-teens for Baltimore, Washington, and Philadelphia (table 1.1). Of course, the rental stock is only approximately half of the total housing stock and is, therefore, considerably less as a proportion of all housing.

TABLE 1.1

Proportion of Public Housing of All Rented Housing in Selected Cities in the United States (%)

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, American Housing Survey 1991.

The emergence of a strong private ownership sector in the housing market in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom in particular has generated a view of owner occupation as the preferred tenure, and preferred over alternative renter forms. According to this view, owner occupation is a positive economic and social good and, in turn, generates “positive” social relations. A number of housing economists and sociologists have argued that people do not seek to own houses for financial reasons; people buy for many reasons, including freedom, choice, security, mobility, pride, and status (MacLennan et al. 1987; Michelson 1977; Saunders 1990).

The process of a shift from a predominantly renter to a predominantly owner society, which happened in many Western societies, did not occur in a vacuum. The massive shift in the United States to a society of owners was facilitated by vigorous government policies that emphasized homeownership. The process includ...