![]()

EDWARDIAN HOME

Early Life 1900–1927

Writing her last book, Milner feels impelled to face her first memory:

It seemed quite preposterous, but it did look as if it had come from the house in London in which I was born. It is of me, quite naked and suspended in a black scarf, which is tied onto the hook of the spring scales that my father used to weigh the fish he caught, this itself hanging from the ceiling. The black scarf would be my sister's, since, according to photos, she would have been wearing a sailor suit, then the fashion for children, with its knotted black scarf in memory of the death of Nelson. I suppose that when fairly new born, I could have been weighed like that, though the ‘memory’ must surely be a construction, because I seem actually to see this baby hanging there, so it must really be a dream. If it is a dream, what has this black scarf memorial of the death of Nelson got to do with me? What now comes to mind is the day my mother called my father ‘the Last Straw’ as well as a time I heard him say to her (rather ruefully) that she ought to have married a Highland Scot with a kilt and a red beard. Surely then, if my so-called first memory was actually a dream, on one level it could have been. It could have been registering the fact of us all being born into a family where my mother and father were secretly, even half-unknown to themselves, battling with disillusion about their marriage, she desperately wanting him to be a hero, he very much aware of not being one?1

Written retrospectively towards the end of a very long life, this is the view of a psychoanalyst, a believer in the unconscious, in the ‘royal road’ of dreams, and a woman with the wisdom of more than ninety years. In another document, written in her fifties, she says one of her first memories is of ‘being praised for being so quick in the lavatory’ and she comments that indeed she has never been able to allow enough time (for thinking) ever since.2 There is also a more conventional way of viewing Marion Milner's arrival in the world and the place her parents had in it.

Figure 1.1 Shooting party 1880s with MM's mother and sister

Born on 1 February 1900, Nina Marion Blackett was ‘brought up in the kindly security of an Edwardian middle-class home’,3 child of Arthur Blackett, ‘a dreamy Victorian Romantic’ who loved poetry, fishing and learning. The Edwardian world into which she was born was one of great comfort for the more privileged of the population, with servants available for those who could afford them. Britain remained a predominant economic power with a massive empire. A small group of aristocrats, landowners and, later, industrialists held political and social power. A prevailing air of certainty, soon to be destroyed by the First World War, would have dominated Milner's childhood.

Her father was not a natural for the commercial vigour of the time. From him she inherited her love of nature and, arguably, her early ambition to be a naturalist, the first of her many callings and careers encompassing literary person, educationalist, psychologist, psychoanalyst, artist and poet.

If her father provided the impetus for the early naturalist bent of Milner's personality, the family of her mother, Caroline Maynard, offered an exemplar in the field of education: Constance Maynard (1849–1935) was head of Westfield College, University of London, from 1881 to 1913, having been previously one of the first female undergraduates accepted to study at Girton College, Cambridge. Another Maynard, Henry Langston Maynard, was master at Westward Ho, a school hated by Rudyard Kipling; he then had his own preparatory school at Nethersole. According to his and Milner's relation, Sir Anthony King, he was ‘by far the best teacher I ever met. ’4

The theme of invention also featured large in the Maynard family tree as it was to do later in Milner's own marriage. Caroline claimed descent from Whitmore ancestors, a political family that had represented Bridgnorth from 1621, when Sir William Whitmore first took his seat in the House of Commons, until 1870. Georgina Whitmore married George Babbage (1791–1821), inventor of the calculating machine, predecessor of the modernday computer, a highlight of family lore and still revered today.

An artistic bent also figures in Caroline Maynard's family: her sister married ‘a rather unsuccessful stockbroker … [who] had some kind of breakdown’ and had a daughter, Dorothy Jones, who had ‘considerable skill as an artist, particularly in pastel.’5 Notable in the family tree on both her mother's and her father's side is the Church. Vigorously anti-clerical and insisting right up until the day of her death that there should be ‘no God’ in her funeral proceedings, Milner was, however, a deeply spiritual person, profoundly versed in the Bible and its poetry and imbued with more than a touch of mysticism. Through the Maynard connection, she was linked with Bishop William Walsham How (1822–1897), famed as the ‘Omnibus Bishop’ because of his habit of travelling to London's East End by bus to makes visits to the poor. In l884, he went on to become Bishop of Wakefield, and, for later generations, was most famous for the hymns he wrote, including ‘For all the Saints who from their labours rest’ and six other hymns in the Church of England's Hymns Ancient and Modern.

The clerical tone is also strong on the Blackett side; Milner's grandfather, Henry Ralph Blackett (1815–1906), was vicar of two London parishes and then, from 1880, of St Andrew's, Croydon. His son, Herbert Blackett (1855– 1885), met an untimely death as a missionary in India; Selwyn Blackett (1854–1937), Herbert's brother, was Rector of Wareham for forty years, and eventually became a Canon of Salisbury; their sister, Adelaide (1860–1952), married Charles Scott Moncrieff, Vicar of Blyth; another sister, Alice (1862–1947), married Leonard Dawson, missionary to the Cree Indians in Canada; and their niece, Annie Schafer (1875–1964), daughter of Ethel Blackett, spent her life as a nun in a Church of England convent in Rottingdean. By contrast, Joseph Maynard (1796–1859), brother-in-law of the Omnibus Bishop, joined the Catholic Apostolic Church – also known as the Irvingites after their leader Edward Irving (1792–1834), a deposed Presbyterian minister.

Successful in a number of fields, the Maynards also had their share of competitive triumphs: Henry Maynard was an acclaimed Monte Carlo rally driver, while Frances Maynard became a County tennis player as well as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the ATS in the Second World War.

Milner's brother, Patrick Blackett, fought in the First World War, being a midshipman on HMS Monmouth (later sunk by the Graf Spee with almost total loss of the crew), then on HMS Carnarvon, going on to become one of the most renowned and controversial physicists of the twentieth century. His independent spirit led him to be renounced as a Stalinist apologist for speaking

Figure 1.2 Nina Blackett with her children, Winifred, Patrick and Marion

out against the British and American development of atomic weapons.6 The strength of his political stands seems markedly different from the innocent apoliticism of his sister, Marion.

Large houses stand out in the family history of the Maynards and the connected families of Whitmore and Sparkes. This has suggested to some previous commentators7 a class disparity between the Blacketts, originally

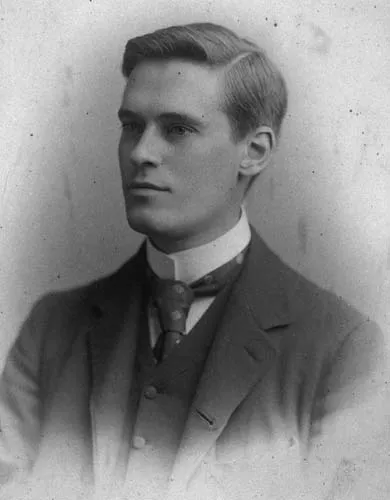

Figure 1.3 Arthur Stuart Blackett (MM's father)

small farmers from Hamsterley in Northumberland, and the maternal line in Milner's family. However, Nick Vine Hall from Australia has traced the Blackett line through twenty-two generations to show its royal descent from Egbert, King of the West Saxons (d. AD 839).8 Whatever the descent of the Blacketts, by the nineteenth century the Maynard family would seem to have been part of a wider, more upper-class tradition.

Figure 1.4 Nina Blackett in eighteenth-century fancy dress

Linked with Milner's great-grandmother, Frances Sparkes, was Dudmaston Hall, near Bridgnorth in Shropshire, inherited by William Whitmore (great-great- grandfather of Milner) in 1774 from Lady Wolryche. Whitmore's daughter – Milner's great-grandmother – married Arundel Francis Sparkes, and in this section of the family are two significant houses – Penywerlodd and St John's – as well. The former, in Wales, might well have appealed to Milner's imagination, with its Gothic legends of a haunting by an eighteenthcentury man in a red hunting-suit, but it is uncertain whether or not Milner ever went there.

A rare Jacobean house, Chastleton, Oxfordshire, near Moreton-in-Marsh, also has family connections. Chastleton was built in 1607/08–1612 by Walter Jones, a wealthy wool merchant, and inherited by John Whitmore (later John Whitmore-Jones), Milner's great-great-uncle. Originally the house was owned by Robert Catesby of Gunpowder Plot fame; it was mortgaged to Jones, and when Catesby was unable to pay, Jones took over, knocked the house down and built the house then inherited by John Whitmore. Today, virtually unchanged for nearly 400 years, it has almost no twenty-first century intrusions and no concessions to modern commercial trends or comfort. Chastleton was acquired by the National Trust in 1991, and Dudmaston was given to the Trust in 1978 by another distant cousin of Milner's, Lady Labouchere.

Though grand in many ways, the Whitmore baronetcy became extinct in the seventeenth century. Some members of the Maynard family like(d) to think they were connected to the Maynard viscounty; this, too, became extinct in the nineteenth century, with substantial estate and fortune passing to Daisy Maynard, who found fame, and even notoriety, as the Countess of Warwick and the mistress of Edward VII.9

Milner's life was rather different from that outlined here: Caroline Maynard may have had the traditional aspirations of an Edwardian mother of her background for her daughters – they were discouraged from going to parties with ‘lower class’ people and Milner retained the Edwardian upper-class voice patterns until the end of her life – but her own personality and, indeed, unhappiness are more individual than this. Milner's early life was arguably troubled by the conflicted marriage of her parents. As Dragstedt has remarked ‘unhappy in her marriage Milner's mother tended to be depressed and not viscerally present to her children.’10 Looking back, Milner writes of her mother's sadness; as she seeks images in her store of familial photographs she finds one of...